Editor’s Note: This is the third of a three-part series focusing on the contraction of the North American shale sector. Read Part I and Part II.

A plan to sell Templar Energy seemed to be going smoothly with 15 bids submitted by the 25 March deadline. And then things fell apart.

On 19 April, certain debtors said they might bid on the assets, according to a Templar summary filed in bankruptcy court.

The statement did not detail why creditors who had wanted to sell and cut their ties to Templar were instead interested in bidding. Given the chaotic state of the oil market at the time, they may well have been looking at really low offers or questions about the financing behind those bids.

Whatever the motivation, an out-of-court deal was no longer possible. Filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection was needed to ensure that any sales to creditors would maximize the amount raised to pay back lenders.

Ultimately assets were sold to an independent oil company, Presidio Petroleum, which offered $91 million for the assets that fit into its operation in western Oklahoma. And Presidio was created to do deals such as this one.

The Fort Worth company, majority-owned by funds managed by Morgan Stanley, calls itself a “21st century startup founded to pursue contrarian opportunities.” It underlines that by saying its mission is to “operate and acquire out-of-favor, developed assets focused on operations optimization and technology.”

Its offer easily exceeded an initial bid by Tapstone Energy, which offered a $65-million stalking-horse bid—a part of the bankruptcy process used to set a floor price for offers—but far less than the more than $400-million valuation of the assets a year earlier.

The huge discount is a sign of the times.

“There is value destruction out there that is not publicly reported,” said Haynes and Boone bankruptcy partner Charlie Beckham. The was one instance where a heavily indebted owner was selling properties for a nominal price “or a willingness of a buyer to assume the P and A [plug and abandonment] liabilities.”

Leap to Pessimism

The pressure on financially weak shale companies has been rising this year, with many getting a push in April when they received the same bad news that Templar received a year ago—the value of their energy loan collateral had been cut.

The consequences of the borrowing base reductions range from reduced access to much needed cash to a loan default if the new oil and gas evaluation is less than the value of the loan.

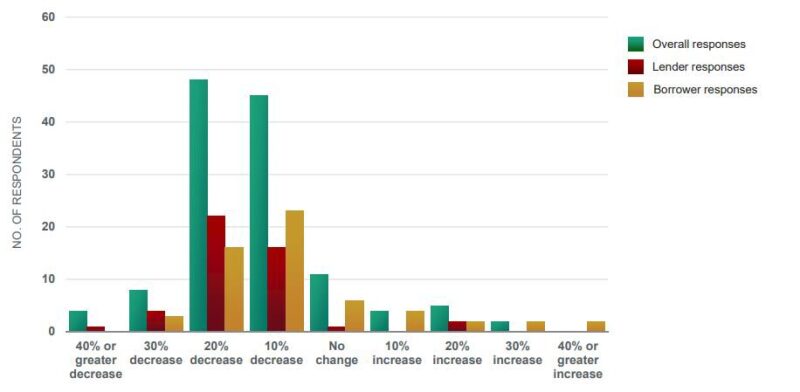

Significant cuts in borrowing bases were predicted in February when Haynes and Boone surveyed 200 borrowers and lenders. The vast majority those surveyed predicted reductions of 10–20%, which could have significant impacts on heavily indebted borrowers.

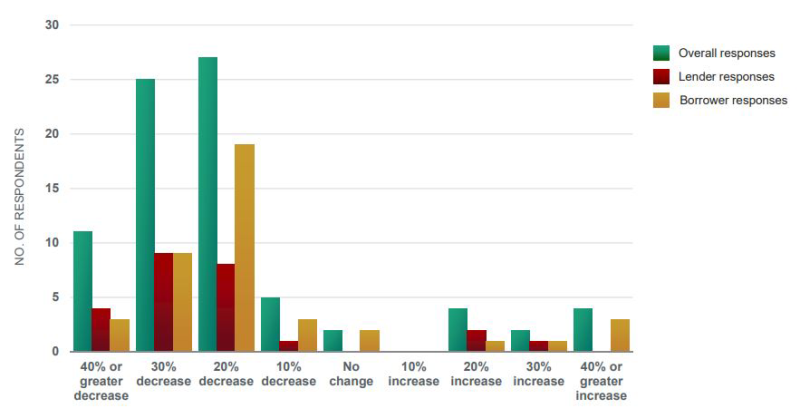

The outlook looked much worse when the survey was repeated after 8 March, around the time that the demand destruction caused by measures to slow the spread of COVID-19 was combined with a price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia that magnified the damage.

When Haynes and Boone repeated the borrowing base survey, the largest group of respondents predicted 20–30% cuts, with fewer expecting a 10% cut and more expecting some 40% reductions.

The surveys suggested the outlook for borrowers is hazardous, but bankers have the final say on the borrowing base evaluations and how that affects corporate borrowers.

For example, Denbury Resources said the bank reaffirmed its $615-million borrowing base, but the company is only allowed to borrow up to $275 million at a time when cash is critical.

Before March 8th

After March 8th

After the oil market crashed, a group of 200 energy lenders and borrowers expected larger reductions in the value of oil and gas assets pledged to secure loans. Source: Haynes and Boone.

Generally, during times when oil market conditions are improving, bankers can wait and see. But while oil prices have rebounded, not all bankers have that luxury. Clark said many midsize banks are in the process of getting out of energy lending altogether by this fall.

And the Wells?

Companies like Templar will go away, but their wells remain.

“In the upstream world a well pumping oil will have someone to operate it,” said Andrew Dittmar, senior mergers and acquisitions analyst with Enverus, adding, “it doesn’t necessarily take a lot of oil to make a well economic for a lean operator.”

Scott Sanderson, a partner with Deloitte, said based on his decades in this business, there have always been opportunities for small players with low overhead to make money on low-producing wells cast off by big oil companies.

Those opportunities are going to be there. Shale companies have been mass-producing horizontal wells for more than a decade.

While more companies are finding themselves forced to sell their assets, there will be plenty of companies that may convince creditors they could thrive—if much of their debt can be shed. Still, they are likely to need to sell wells and acreage that do not fit into their plans and to bring in some cash.

Nearly half of those assets are owned by companies defined as “superfluous” by Deloitte. Those with loans coming due or significant borrowing base reductions will be looking to sell assets.

Buyers need to beware because weak companies often fall short in more than financial engineering. Low operational rankings may reflect poorly engineered field designs or wellbores that undulate up and down, allowing water to accumulate in low spots and reducing production or blocking it altogether. For many companies tightly spaced wells were the norm until it became clear that overlapping fractures made it a costly way to accelerate production, not increase it.

An anonymous commenter in the recent quarterly energy survey by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City predicted a glut of wells for sale that no one will want to own.

“The US orphaned well inventory will explode to new highs if the current price continues. In addition, I don’t see a market for stripper wells in the future. So many producers will be surrendering wells.”

So far, Dittmar said their very rough estimate of oil and gas assets for sale is about $5 billion.

Oil prices have done better than expected in the bleak early days of this crash but remain about $10 below the $50/bbl breakeven level for many shale producers.

A buyer who is optimistic about future prices may well be able to lower the breakeven price by buying old shale wells at bargain prices. If these were conventional wells, the rate-of-return calculation is simple enough.

“If I knew I could pick up [wells producing] 3,000 B/D and knew what the lifting costs were and I knew the decline rate at 7%,” it would easy enough to evaluate the return on the deal, Sanderson said.

But studies of decline rates in the Permian have often observed annual decline rates twice that high for wells 5 years and older.

While rod pumps are used for both conventional and unconventional wells, modeling production from older horizontal wells is an area of argument among production experts and reserve engineers.

At the moment it can be hard to know what the market price should be for assets because there have been so few deals lately. Dittmar said there is a frustrating lack of recent asset sales data to use to estimate what liquids-rich shale acreage should sell for, even in the Permian.

The problem is magnified in out-of-favor oil-producing basins—essentially everything but the Permian.

Dittmar and others wonder who the buyers will be. A year ago, there was talk of the majors dominating the Permian, but “now they have problems of their own.”

He expects to see private-equity investors looking for money-making opportunities. But in the long run he sees a large role for traditional independents, likely owned by a “family or a wildcatter” that are “not beholden to institutional investors.”

Templar is trying to sell 273,400 acres of land in three low-profile plays: the western Anadarko, Canyon Resources, and northeast STACK play. The summary said it has 2,165 wells producing 18,000 BOED—or about 8.3 BOED per well—from a mix of conventional and unconventional wells.

The value of those barrels is considerably less than the benchmark oil price because the majority of it is likely gas—more than half of the reserves are dry gas—followed by gas liquids and then oil.

Buyers would be up against a deadline to drill and produce on 25% of those acres because those leases are not held by production. Nearly half the wells are operated by another company. That may be a positive for buyers at a time when there has been demand for wells yielding steady income.

Local knowledge is critical when buying into a shale play. In the STACK, where Templar’s website played up the many potential production horizons, experience has shown the zones often interconnect so one well will produce from many layers, but the results vary.

Tapstone plays up its knowledge of the STACK on its website. But like Templar, it was born as a private-equity-backed shale startup which ultimately filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. It survived as a going concern, in part, due to a $50-million investment by a New York firm, Kennedy Lewis Investment Management, which is looking for “acquisitive growth.”

This is the third summer running that Presidio has made a large acquisition. Its website describes the company: “We run against the herd. It’s not what you buy, it’s what you pay and how you operate it.”

It will be a slower-moving business with engineers focused on financially sustainable growth and cost-effective production gains.

The future of shale requires engineers and technical experts “finding cheaper ways to drill and produce,” Clark said.

There will be fewer companies in shale, but Sanderson does not see it happening in a hurry. “Typically in our industry, old operations do not die, they fade away,” he said.