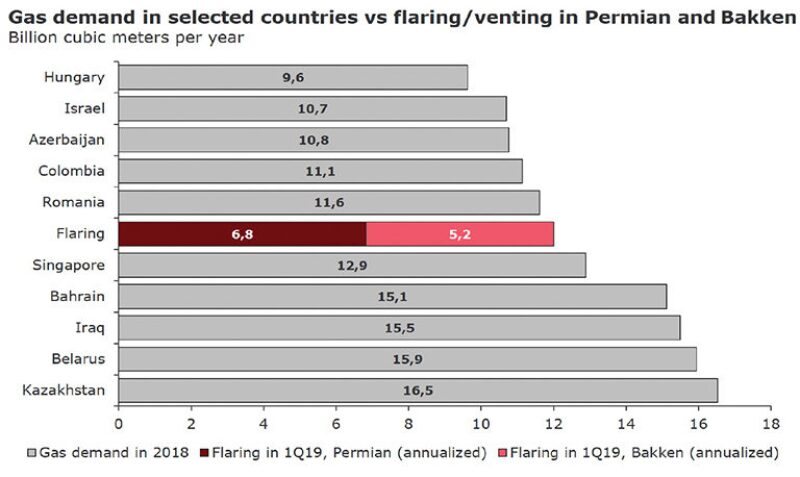

Natural gas flared in just two major US shale plays exceeded the amount of gas consumed last year in Colombia and Israel.

The prolific waste from the Permian and the Bakken (Figs. 1 and 2) is a side effect of rising oil production in plays where gas growth is so strong pipeline construction cannot keep up.

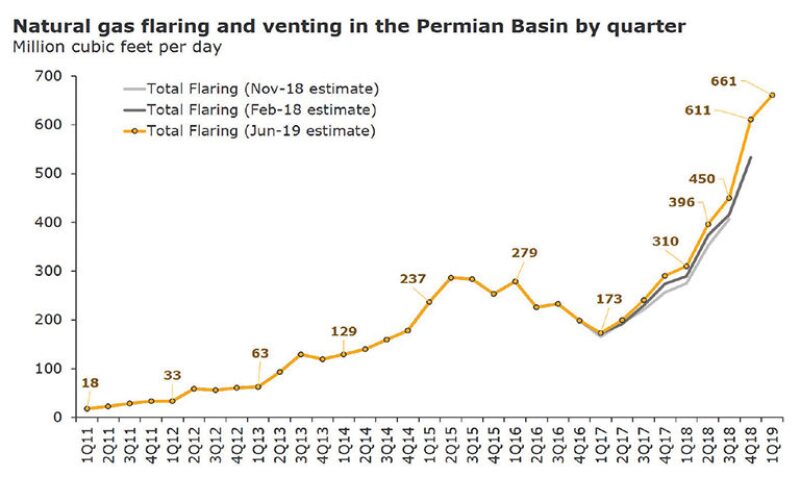

basin (million ft3/d) has risen sharply since early 2017. Source: Rystad Energy.

Flaring is a glaring reminder of the realities of the never-ending rush to drill that is driving down the cost of oil and gas around the globe.

These oil-producing wells also produce more gas than processing plants and pipelines can move to market.

Pipelines and refineries have recognized that ultralight oil in the Permian is fundamentally different from West Texas Intermediate (WTI), with a makeup that puts it somewhere between oil and gas liquids.

As those wells age, oil production falls as the output shifts to gas.

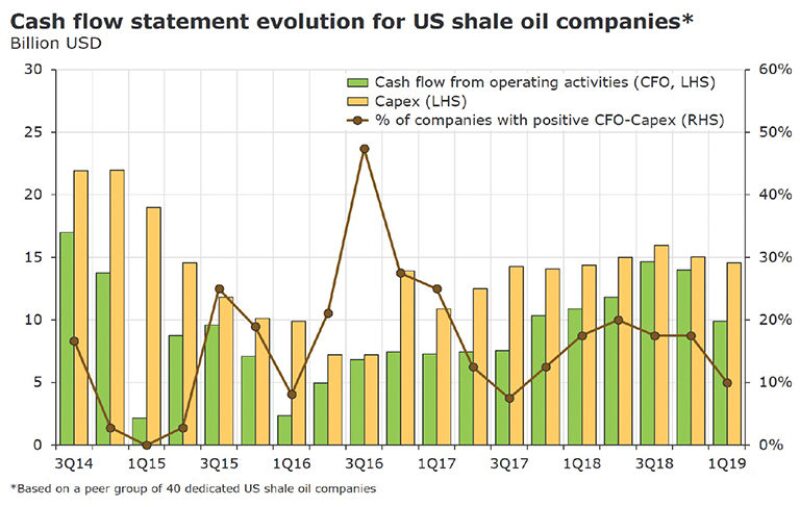

And the cost of sustaining production for the vast majority of producers has consistently exceeded the cash generated by these wells (Fig. 3). The gap between capital expenditures and revenues was “a staggering $4.7 billion” during the first quarter of 2019, according to a study by Alisa Lukash, a senior analyst on Rystad Energy’s North American shale team, who described it as a “tremendous overspend.”

Both the US Energy Information Administration (EIA) and Rystad have raised outlooks that already predicted strong US oil growth. Flaring growth and overspending have accompanied a rebound in growth in the Permian and Bakken, which are the flaring leaders by far in the US.

More than half of the total comes from the Permian, which has surpassed the Bakken by more than tripling the volume of gas burned per day since early 2017. The severity of the problem, though, is more acute in the Bakken. While Rystad said about 5% of the Permian gas is flared, in the Bakken, 19% of the gas is flared, according to the oil and gas division of the North Dakota Industrial Commission.

The Permian produces far more gas but has the advantage of being close to growing markets for it—chemical plants, export pipelines to Mexico, and natural gas liquefaction facilities—while North Dakota is a distant option for Midwestern markets well supplied by other plays.

Limited pipeline capacity means those shippers without contracts ensuring they can move their gas are paid little or less than nothing—prices at Waha gas hub in west Texas repeatedly sank into negative territory over the winter, and pipeline shortages will linger until a big new pipeline goes into service.

Oil pipeline construction also has lagged supply growth in the Bakken. Trains and trucks can ship oil, but that is a costly option. North Dakota oil regulators reported that Bakken prices hovered around $50/bbl early this year when the benchmark US oil grade was about $10/bbl higher.

Pushing the Tempo

Gas flaring has been an accepted price for rapidly rising US oil production, but, based on the results of shale producers, it is hard to know why producers are in such a hurry.

Recent price declines because of rising production will make it harder for shale oil producers to meet the demands of investors looking for a payoff on the billions of dollars that fueled growth.

While a lot of talk has centered on shifting the focus from growth to earnings, when Rystad analyzed the performance of 40 companies in the shale oil business, it found that only four took in more cash than they spent on capital expenditures during the first quarter. That is a step backward from previous quarters, when twice as many companies were in the positive zone.

This measure of exploration and production cash flow is a useful guide for the return on wells, where most of the ultimate revenue is generated early in the life of the well. It does not cover financial sources of income such as hedging—using investment strategies that pay off when oil prices drop below a set level—nor does it include corporate costs such as the engineers on the payroll.

The gap may narrow later this year when wells drilled in the first quarter are finally completed. Still, Lukash said the cash flow data were in line with “dismal first-quarter earnings,” which served to “cement negative market sentiment.”

Bad blood with investors and bankers magnifies the problems of operators who have depended on outside sources of cash to fill the gap created by overspending. Since oil prices fell last year, Lukash reported that “no US shale company has made a public offering.”

Executives acknowledge the problem. For example, in a recent earnings call, Parsley Energy’s Chief Executive Officer Matt Gallagher provided a progress report on the company’s plan to become cash-flow positive.

He said the program was designed to answer some basic questions: “If we put a dollar in the ground, are we getting well over a dollar back? Do we have the scale to deploy a development dollar as efficiently as any other peers in the basin? Does our asset base allow us to consistently grow our cash flow, and does that cash-flow growth accrue to shareholders?”

His answers were: They were making progress in what is clearly a long-term program that has reduced its working rigs from 16 to 12, lowered its drilling and completion costs, and reduced its staff by 8%. “This [job] decision was not easy and was not made lightly, but it underscores our commitment to free cash flow and disciplined returns,” said Ryan Dalton, chief financial officer for Parsley.

As for whether Parsley is big enough to compete, Gallagher said it is large enough to negotiate competitive deals with service providers, pipelines, and banks.

As for who is too small, Gallagher said there are “more than 50 operators in the Permian running two rigs or fewer. It is tough to compete at that size,” he said.

Size is increasingly being equated with survival among independent unconventional producers. A recent EIA study showed that only a handful of the largest companies in its 43-company database were generating more cash than they were spending on capital expenditures.

Lukash said a widely followed measure of financial risk shows it has gone up since last October for the 40 companies it tracks, but it “is nowhere close to what we have witnessed back in 2015–2016 in the energy sector,” she said. The risk level is much lower for large independents, such as Pioneer Natural Resource, Concho Resources, and ConocoPhillips, who are at a level comparable to major oil companies, she said.

Tilting Toward Gas

Flaring growth has long accompanied rising oil production, but, in the Bakken and Permian, gas growth is outstripping liquids growth.

In the Bakken, the state reported that gas production was rising 70% faster than oil. The volume of North Dakota gas production rose 6.4% from February to March, while oil output went up 3.7%.

In the Permian, oil production dipped during a 3-month period when gas production rose by 1 Bcf/D to 14 Bcf/D, said Artem Abramov, head of shale research at Rystad Energy. That steady increase is “the driving force behind increased venting and flaring.”

The gas production rise during the first quarter of 2019 is equal to half the capacity on the Gulf Coast Express Pipeline, which Kinder Morgan plans to open this fall. Earlier this week, Marathon Petroleum and three partners announced they decided to build a pipeline, known as the Whistler Pipeline, designed to carry 2 Bcf/D from the Waha hub to the Agua Dulce hub near Corpus Christi, Texas.

The growing gas flow also suggests this oil play, which has been a significant gas producer, is getting gassier. A major part of this is because of areas within the Permian that produce mostly gas and gas liquids, such as Apache’s Alpine High play.

The oil coming out of this play is looking gassier as well. The emerging name for this ultralight oil is West Texas Light. It was created to label oil too light to meet the standard for the benchmark WTI. An Argus Media story reported that pipelines were defining lights as liquids with an API gravity from 45 to 50 that it said fall between “WTI and condensate but with varying dividing lines.”

Shale oil wells also produce more gas over time, starting slowly and eventually shifting swiftly to gas. An EIA report on the Bakken, which is one of the first shale oil plays, explained:

“The gas/oil ratio tends to rise only gradually over an extended period of time before reaching a certain point at which it then increases significantly.” That takeoff occurs when the production reaches the boundary of the producing zone around the well. At that point, the pressure level is uniformly below the point at which gas escapes from the liquid—the bubblepoint—allowing gas to flow out faster.

No Stopping Now

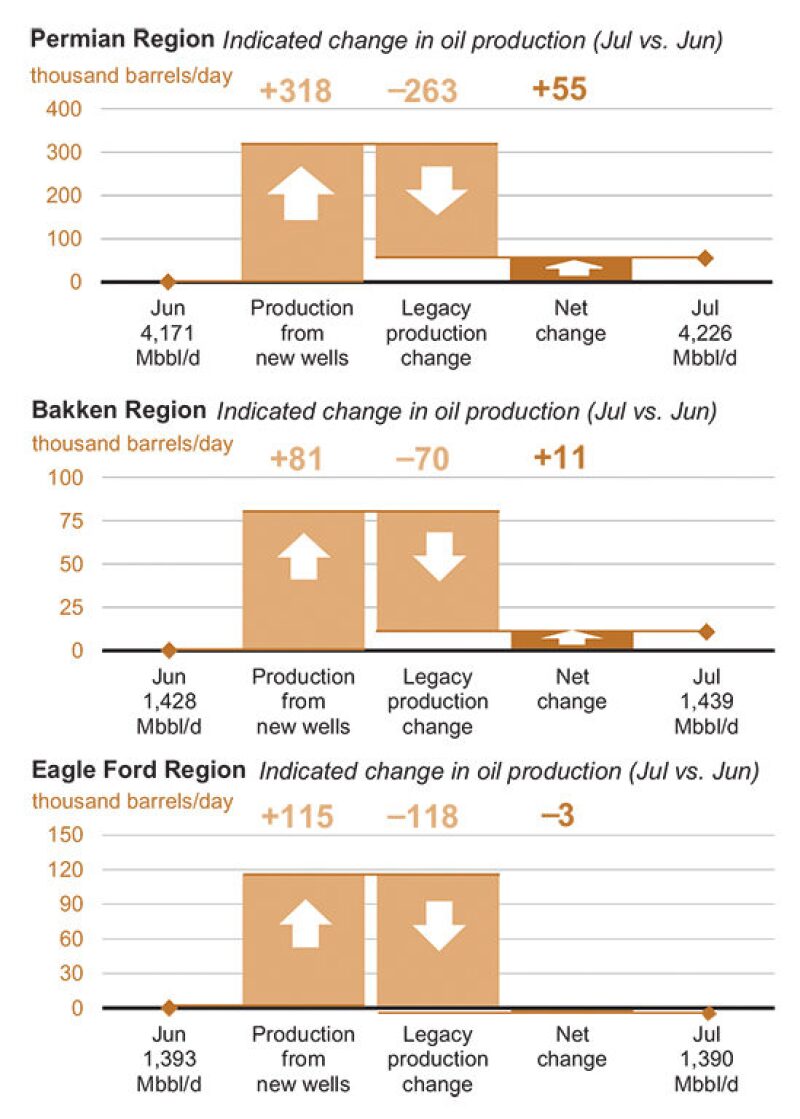

In most businesses, significant spending now is required to bring in cash later. In the shale oil business, constant spending is required just to stay even.

Three charts from the EIA show why (Fig. 4). In the Permian and Bakken, more than 80% of the new production was needed to replace what was lost in May, and, in the Eagle Ford, new production came up just short of the breakeven point.

At a glance, these charts show why so many companies that are burning cash have not slowed down. The growth imperative was explained in a recent episode of The Drilldown, a podcast from John and Richard Spears, whose company Spears and Associates closely tracks the service sector. John Spears estimated that about 11,000 new wells were needed in 2018 to sustain US production and that the total rises to 14,000 this year. The estimates were based on EIA data on the monthly decline rates for unconventional wells and also the productivity levels for the wells.

The well total rose for two reasons:

- As more new wells are added to push up production, the monthly decline, which must be filled with new production, also increases. Spears estimated that currently at 550,000 bbl per month.

- Production per new well also is dropping, so even more wells are needed to fill the gap.

For individual companies, the effect will vary on the basis of their size and well productivity, but, until someone finds a way to flatten the decline curves on those wells, it will not be avoidable.