Russia has taken its first steps toward regulating carbon emissions since joining the Paris climate accords in 2019 with President Vladimir Putin’s signing of legislation in early July requiring the country’s largest greenhouse-gas emitters (GHG) to report carbon data to a new government agency.

The new law makes carbon reporting mandatory as of January 2023 for companies emitting 150,000 tons of carbon or more, and January 2025 for carbon emitters in the 50,000 to 150,000 range, according to the Russian news agency TASS.

"An accounting system is being introduced, carbon dioxide is becoming a substance subject to government regulation,” Greenpeace spokesman Vladimir Chuprov told Reuters. “An emissions accounting and reduction system is emerging. This is a prerequisite for a greenhouse-gas emissions trading system."

With such measures in place, Russia aims to meet its Paris agreement pledge to reduce emissions by 2030 to 70% of 1990 levels.

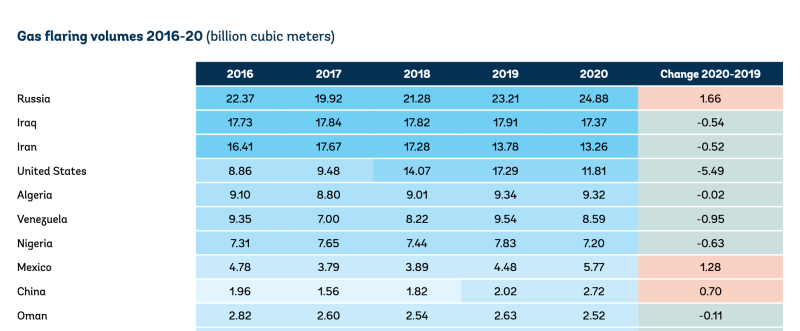

Not surprisingly, Russia’s oil and gas industry will bear the brunt of the new law. Russia flares more associated gas than any other country in the world—24.6 Bcm in 2020, an 8% increase year-on-year, according to the World Bank Gas Flaring Tracking Report published in April (Fig. 1).

The problem concerns not only the upstream but also Russia’s mid and downstream, including the petrochemical industry which has grown in recent years as Russia diversifies away from dependance on crude exports and moves toward producing more value-added petroleum products for both export and domestic consumption.

Flaring Uptick Hits the Arctic, East Siberia

Russia started to take flaring seriously after a 2012 World Bank report estimated that the practice cost the economy $5 billion in annual losses.

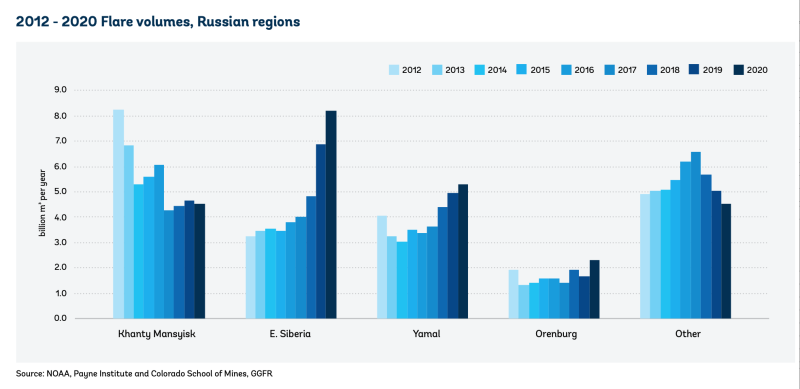

As a result, flaring has become less problematic in Russia’s traditional oil-producing regions. For example, West Siberia’s semiautonomous Khanty-Mansiysk region (KMAO), home to the country’s largest oil field and 70% of Russian oil production, has seen flaring drop by 80% since the mid-2000s.

As of yearend 2014, KMAO claimed it had met federal requirements to use 95% of the gas it might otherwise flare, the World Bank reported.

But as flaring has declined in West Siberia, carbon emissions are rising in new development areas such as Yamal in the Arctic, the site of Russia’s major new gas and liquefied natural gas (LNG) projects; also, in East Siberia where greenfield development is occurring in remote areas that lack the infrastructure to capture and transport associated gas (Fig. 2).

Oil and gas exports will account for 40% of Russia’s 2021 state budget, according to Bloomberg, and as the European appetite for oil wanes, Russia is boosting investment in East Siberian production such as Rosneft’s Vostok project to supply Asia where oil demand continues to grow.

In the midstream and petrochemicals sector, Russia’s largest petrochemical producer, SIBUR, is in talks with Baker Hughes to optimize flare performance across SIBUR’s industrial asset base to ensure 98% or more flare combustion efficiency, SIBUR announced in a news release.

SIBUR and Bentley Nevada, a Baker Hughes business, signed a memorandum of understanding in June at Russia’s C-suite gathering at the St. Petersburg Economic Forum to explore implementing Bentley Nevada’s System 1 remote machine conditioning monitoring software platform and other technologies, including flare monitoring and cybersecurity at more than 10 SIBUR sites.

Also in St. Petersburg, Russian oil major Gazprom Neft announced it had agreed to collaborate with metallurgy companies Severstal and EVRAZ on hydrogen production, transportation, storage, and utilization of technologies, and on reducing carbon emissions.

The companies aim to convert some steelmaking infrastructure to hydrogen to reduce GHG. In its news release, Gazprom Neft noted that “basic blue-hydrogen” production technologies involving steam methane reformation (SMR) involve actually recycling carbon dioxide.”

Gazprom Neft, through its joint venture with the Serbian national oil company NIS, has been involved in a project to collect and purify high-CO2-content natural gas from various fields since 2015. The CO2 extracted is then injected into developed reservoirs at a depth of more than 2500 m, according to the news release.

In St. Petersburg, Gazprom Neft and Shell also reaffirmed their intention to collaborate in deploying carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) solutions at their two Russian joint ventures: Salym Petroleum Development which is producing the Salym group of fields in West Siberia’s Khanty-Mansiysk; and a joint venture to explore and develop a major geological prospecting cluster covering the Pukhutsyayakhsky and Leskinsky license blocks in the Gydan Peninsula in greenfield Yamal.

Russia’s 2023 target to start GHG reporting coincides with the same 2023 date when the EU will implement a carbon border tax that The Bank of Russia estimates may cost Russia up to 8.2 billion euros ($9.7 billion) a year; Russia’s Ministry of Oil estimates that domestic oil and gas companies risk losing up to $4 billion, Bloomberg reported.

“Russia needs a deal with the Europeans to recognize our efforts in the transition to a green economy,” the country’s Finance Minister Anton Siluanov was quoted as saying, adding that Russian efforts to reduce environmental harm should be considered when determining the cross-border tax obligations of Russian exporters.

Siluanov will make his case at the G-20’s gathering of finance ministers and central bankers that starts July 9 in Venice, Italy. Though the meeting's intent is to decide how to present a proposal for a 15% corporate global income tax at the G-20 leaders' summit in Rome in October, a session on climate change will be held on the sidelines, according to Voice of America.