July’s drop in oil prices to below USD 50/bbl reminded the shale industry that the hard times may be around for a while and that operators need to continue working on their cost reduction plans. At the recent 2015 Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, a major theme was how companies can improve performance without increasing the size of their budget.

Some companies are looking to work closer with other companies to share knowledge and technology that may yield higher production. Others are looking inward for ideas that may reduce risk and improve the bottom line.

Barry Biggs, vice president of onshore operations at Hess, described the lean approach that the company has adopted, which includes using “an army of problem solvers.” Counter to their moniker, this cadre of key employees are not exclusively working on problems. He said that too often, operators are focused more on finding out what went wrong in an operation rather than what went right.

“Well, flip that. What is the root cause analysis of things you are doing well?” he asked. “It is a mental shift that we can use to try to drive improvement.”

He credited this business structure with helping Hess drive down costs by 50% in the Bakken Shale from 2012 to 2015. Biggs said it has also been critical in allowing the company to develop the Utica Shale faster than the Bakken despite the geologic differences of the two plays.

Instead of dictating orders from the top down, this leadership style asks questions, welcomes debate, and relies on collaboration while still holding people accountable for meeting their goals, Biggs said.

One example of its management strategy is written on the walls of the company’s asset collaboration rooms, where team leaders post their business plans and status reports for all to see. Once a week, engineers and executives go around the room trying to solve whatever problems that are being encountered. Biggs said this visual approach of project management “is much more powerful than a report that gets circulated around.”

While operators trim their own fat, a hefty portion of the savings they are seeing today are a result of the pressure on service companies to lower their prices, in many cases by about 30% or more. “However, we can’t get to where we need to be with cost reductions alone,” said Peter Richter, vice president of unconventional resources at Schlumberger. “These cost reductions, while they are nice for the immediate economics, they are not sustainable for the long term.”

To emerge from the downturn stronger than before it entered in, Richter said the unconventional sector needs to adopt an align-and-conquer strategy. By integrating data and collaborating more on drilling and completion operations, both efficiency and production can be improved, he said.

“We really need to think about if we are going to drill this well, where do we place it? Where is the optimum place for the fractures and stimulation, and then make sure we steer it in the right place,” he asked.

EIA Administrator: US No. 1 in Global Production

The biggest question for those working in the unconventional industry this year is when will oil prices begin to rise again? Adam Sieminski, administrator of the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), shared his thoughts on the topic in the opening session of the conference.

He framed the situation by noting that the US is officially the largest producer of oil, gas, and condensate in the world, all thanks to the shale revolution. The historic resurgence in US production is a testament to the prowess of unconventional technology and engineering, but it has also left the shale industry a victim of its own success.

Last year, the global supply of oil grew by almost 2 million B/D from the previous year. Sieminski said that most of the added production came from the shale fields of the US and Canada, with the effect of halving oil prices from around USD 100 to around USD 50 per bbl.

“In a world where global demand is only growing by a million barrels a day if you are conservative, and a million-and-a-half if you are wildly optimistic, 2 million B/D growth from the United States and Canada is not going to work,” he said.

For industry professionals seeking relief from low prices, the EIA is not offering much hope. By next year, he said, North American shale production will slow down, but it may not send prices much higher. The EIA is estimating that the US will produce an average of 9.4 million B/D of crude this year and about 9 million B/D next year.

However, the EIA’s estimate for the average price of US benchmark crude, West Texas Intermediate (WTI), for next year is USD 54/bbl. The assumed lifting of sanctions on Iran is expected to be a major factor in sustaining low oil prices through next year. Sieminski pointed out that the model used to forecast prices into next year showed that WTI could be as low as USD 30 or as high as USD 100 per bbl.

Regarding the uncertainty of prices, he said, “It is raising some really interesting questions about what do you do as a company. I think the answer is manage your costs to weather through the problem.”

One factor that may alter the price of WTI in favor of shale producers is if the federal government ended its ban on oil exports. One of the biggest roadblocks to such a policy reversal is the concern that if exports were allowed, US consumers would suffer from higher gasoline prices. Sieminski explained that the EIA’s findings on this topic, which suggest an end to the crude export ban, would be a win-win for both consumers and the shale industry.

US gasoline prices are tied to the global gasoline markets, which in turn are tied to the global oil markets, but not WTI prices. “So if you did allow crude oil exports, WTI would go up, and gasoline prices would not only not go up, but they might go down,” he said. “Because more crude oil on the global market would lower global crude price, which would bring gasoline prices down.”

New Technology, Old Data

On the technology front, Richter listed several things in the works that may bring greater returns for each well drilled. Multilateral wells, new proppant transport fluids, and automated drilling rigs are just a few of the ideas he touched on.

He also said that Schlumberger is collaborating with five operators in a refracturing consortium in the Eagle Ford Shale that is aimed at finding the best way to increase production from older wells.

In his presentation, Richter showed a sample of six refractured oil wells that saw improvements of the initial production rate between 48% and 115%. “If you get the right candidate in the right zone, you can have very positive results,” he said. “But the candidate selection and screening is absolutely critical and that is where the data come into play.”

Figuring out the optimal completion design for any particular play is something many are still working on. Biggs said Hess has found that the longer laterals of about 10,000 ft are clearly the most profitable wells. He added that the company is experimenting with 50-stage wells that use sliding sleeves in North Dakota.

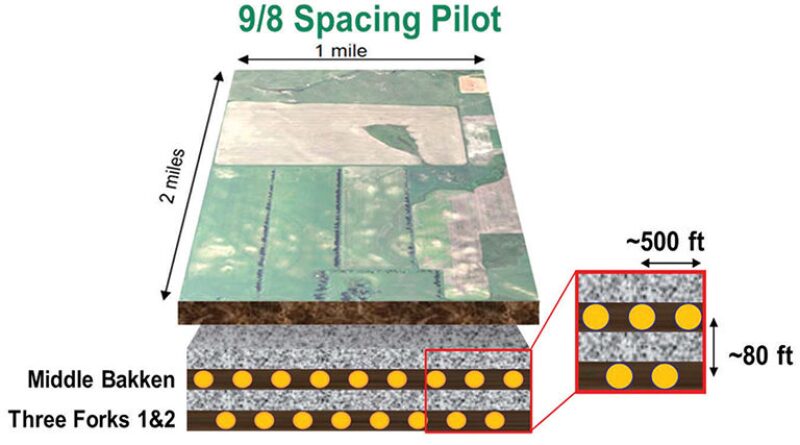

Hess is also running a down spacing pilot that involves drilling nine wells in the Bakken Shale and eight wells in the Three Forks, per 1-mile section. “That is making a big difference in terms of adding to the [estimated ultimate recovery] base in North Dakota,” Biggs said.

And after a decade of drilling and with more than 70,000 operating horizontal wells in the US, there are many lessons to be learned for companies in the shale game. Some should come at little to no cost. Claudia Hackbarth, manager of unconventional gas and tight oil research and development at Shell, said the company is among those taking advantage of the “free data that we can collect and is hiding in plain sight.”

Examples of the free, or at least already paid for, information that Hackbarth highlighted during her luncheon speech includes logging data, production histories, rock and fluid analyses, and aggregated public databases such as FracFocus, the chemical registry that tracks stimulation treatments across North America.

She said all this information can be used to narrow down test criteria for moving forward with future development plans. “I think that would definitely cut costs because it would help us hone in much more quickly on our optimized designs,” she said.

Another tactic that some companies are adopting means setting aside competition for the sake of the greater good. “We trade a lot of data with offsetting operators. You can save a lot of money on data if you do not have to do it all yourself,” said Gervasio Barzola, vice president of subsurface and development of the Southern Wolfcamp Asset Team at Pioneer Natural Resources.