Begin a conversation about jobs in the oil and gas industry with people employed in the sector, or who have left their jobs voluntarily or involuntarily, and then settle in for a lengthy (maybe even heated) discussion of the pros and cons. Job availability, compensation, working conditions, opportunities for advancement, and work/life balance all come into play.

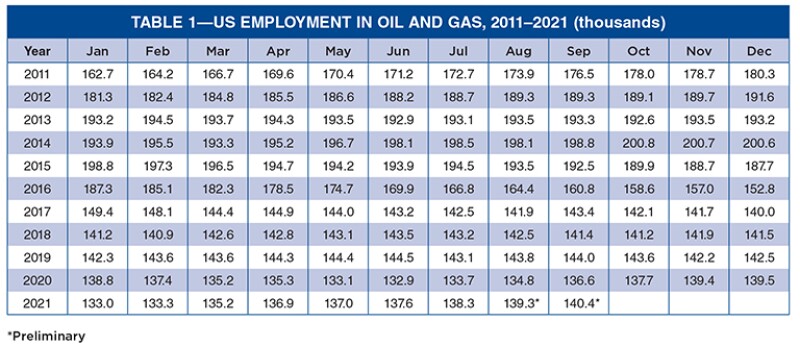

But what does the employment in our industry look like after the tumultuous past 18 months? The US Department of Labor report released in early October showed the total of the monthly incremental increases since January 2021 was 7,400 in September, bringing the number of people employed in the US oil and gas industry from 133,000 to 140,400. This is nearly back to the level seen at the end of 2019 (142,500) but nowhere near the peak of October 2014 when nearly 201,000 people were employed (Table 1).

The reasons for the lower levels of employment are many, among the most glaring are the industry downturns in 2016 and another in 2020 because of the global effects of the pandemic. As SPE President Kamel Ben-Naceur writes this month, the downturns brought with them a pullback in upstream spending of 26% in 2016 and 31% last year.

As a result, cost cutting included the cancellation or delay of capital projects, selling of assets, and mergers and acquisitions to wring out savings wherever possible, ultimately also cutting headcounts. Also playing a significant role are technological advances and efficiency gains achieved in the things that make our industry hum. For example, automation of equipment such as rigs and the remarkable leaps in digitization in all functions, be it monitoring, modeling, or data interpretation and analysis. All disciplines have been touched by these advancements.

And it cannot be ignored that retirements and attrition also contributed to the numbers, many of which were decisions made as the downturns took their toll.

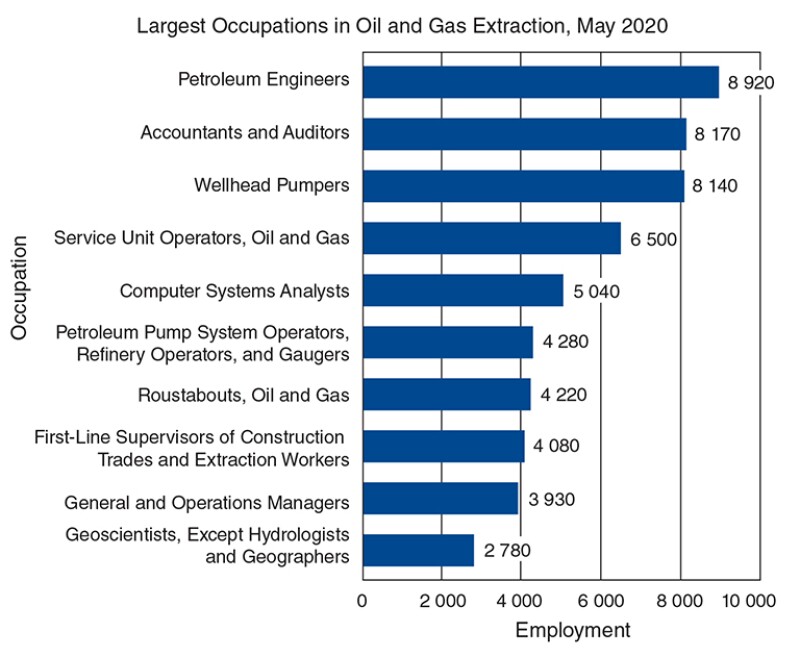

Fig. 1 shows the most recent breakdown of the 10 occupations accounting for the most employees in the oil and gas sector (May 2020). The numbers total 56,060, accounting for 44% of the total shown in the table for the same month (133,100).

Leading the tally are petroleum engineers, accountants and auditors, and wellhead pumpers. While the numbers may have changed since May 2020, the graph serves as an indicator of the roles sustaining the industry.

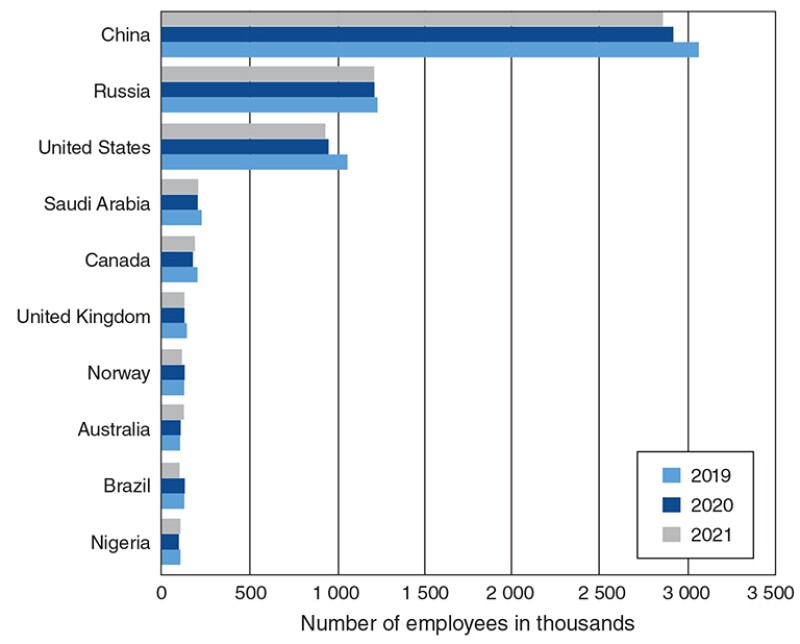

Providing another comparison, Fig. 2 shows the changes in industry employment globally. Even though the collection of the data may not have used the same criteria as the US Bureau of Labor, the figure shows the comparative decreases in 2021 compared with 2019.

Is it realistic to think the peak could be seen again? For all industries, the dynamics of unexpected change and the need for quick adaptation are often unpredictable. No one predicted the global effects the pandemic would bring upon people, business, and trade, or how long they would linger. Many crystal balls were cloudy or shattered.

The global move to cleaner energy sources to meet climate goals also affected the types of employment. As the transition progresses, it remains to be seen how roles will shift or change along with business strategies. Demand remains strong and the levels of investment low.

The foreseeable short-term (possibly longer?) supply/demand imbalance also provides possibilities for roles in managing demand to ensure energy security, upskilling, and digital, among others.

So, back to the question: Is it realistic to think the peak of 2014 could be seen again? Perhaps as the industry’s settling in for the long haul (if that is possible) continues, the types of jobs will change and a peak of employees in the “energy” industry will achieve or bypass the historical peak.

Disclaimer: My crystal ball offers no more clarity in prognostications than others.