For most of the past 160 years, the exploration and production (E&P) sector earned outsized economic rent for finding new oil and gas (O&G) resources and making them economically viable for production. This was possible because of the perceived scarcity of such resources; demand expectations for hydrocarbon products far exceeded their likely supply.

During that period, E&P companies focused on building functional expertise to enable growth and operate assets safely. Exploration and appraisal capabilities were particularly revered as key drivers of value. Other areas of the value chain such as field production management, logistics, or even marketing were not seen as critically differentiating. Understandably, building expertise in those areas was never made the primary focus.

What a difference a decade makes.

Perpetual Disruption Is the New Normal

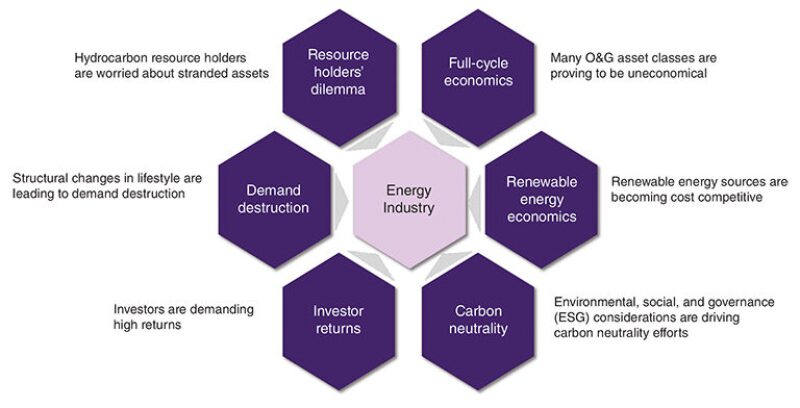

Today, we live in a completely different world. The challenges facing upstream companies simply did not exist 10 years ago. Six compressive forces, in particular, are bringing about a sea change in the industry.

Earlier this year, COVID-19 brought with it a sharp and palpable drop in demand for transportation-related crude. With the dramatic structural changes we have made to the ways we live and work in response to the pandemic, low crude demand is expected to continue. This will only exacerbate resource holders’ concerns about supply overabundance. E&P companies that hold hydrocarbon resources were already worried that the resources they own could go unmonetized. Now, that threat is stronger than ever. So is the incentive to monetize their resources as quickly as possible. Ironically, their actions to do so will make the oversupply situation worse.

Beyond the issues of supply and demand, the industry’s general economic climate is wreaking havoc. O&G companies typically focus on half-cycle economics or lifting costs when making production decisions. That is because land acquisition and development costs are considered sunk. If oil prices stay in the $40–50/bbl range, many asset classes will simply be uneconomical from a full-cycle standpoint.

Investors have taken notice. They are quite concerned about the industry’s poor return on capital employed. As investors run out of patience, E&P players need to become more selective in terms of the projects they undertake. That imperative is complicated, however, by the fact that they need to minimize their environmental, social, and governance impacts to retain their social licenses to operate. Their projects must be profitable—and sustainable.

As if these headwinds facing the industry were not strong enough, there is also the growing threat from nonhydrocarbon competitors. The levelized cost of energy is rapidly decreasing for renewable sources like solar, wind, and biomass. Even without government subsidies, they are poised to displace hydrocarbon energy sources. When combined with cost-effective and high-capacity batteries, the penetration of renewables into the energy sector will be fast and likely unstoppable. In regions that will enable customers to choose their energy sources, the risk of stranded assets for E&P companies becomes very real.

While these pressures are universal, the degree of compressive forces they exert differ across geography and company type. For example, carbon neutrality may not yet be a primary driver of change for some national oil companies (NOCs) in Asia, Africa, and Latin America; it is, however, becoming very important for supermajors and NOCs in Europe. Similarly, the relative economics of renewables are not yet compelling in several hydrocarbon-resource-rich countries. Some may argue that NOCs are not under as much investor pressure as publicly traded companies. Actually, in many cases, the pressure for NOC profitability from governments may actually be higher than the pressure on publicly traded companies.

The bottom line is that E&P companies—NOCs, supermajors, and independents—are under a lot of pressure from many directions (Fig. 1). While their individual circumstances may vary, they all must take decisive action to pivot away from “business as usual.” Fortunately, there are several new growth models they can pursue.

Returns, Not Reserves

Oil and gas are the most important sources of energy today. That is not changing anytime soon. In fact, our analysis estimates that fossil fuels will still provide close to 50% of the energy mix in 2050.

Many O&G companies see this as a justification to continue operating much as they always have, albeit while adhering to more-stringent carbon regulations and strengthening their operational and commercial agility. For them, market centricity becomes the name of the game. The new world will warrant a “production system” view, which connects dynamically the various areas across the value chain, from exploration to marketing, to best manage market volatility. Other companies see the 50% decline in fossil-fuel consumption by 2050 as a catalyst to abandon O&G altogether. They are succumbing to the compressive forces they face and looking for alternative paths to profitability. The move to renewables holds particular allure.

The truth is that sunsetting or resetting their O&G capabilities are not the only options for E&P companies. There is a broad middle ground of potential profitability—and renewed investor interest. As the importance of exploration and appraisal recedes, we believe three new pathways will open up three new futures for today’s E&P players: developer, producer, or marketer.

- Developers will engage in capital projects targeted at developing existing or new fields. They will be measured on their ability to deliver these projects in a lean and efficient fashion, on time and on cost. These companies will be similar to today’s engineering, procurement, and construction companies.

- Producers will aim to maximize production from a set of wells in a field. They will ensure that downtime is minimized, and wells are producing to their maximum potential. They will focus on optimizing all aspects of an integrated production system.

- Marketers will manage the inventory of crude and natural gas. They will be in the business of sending the right molecules to the right end use at the right time to capture the most economic rent.

The risk-return profile of each of the above pathways is quite unique. Markets, which may encourage the breakup of integrated upstream companies into these three types of pure plays, will assess each company against benchmarks corresponding to its new business model. For upstream companies that remain integrated and follow all three pathways above, investors will demand greater transparency. And they will expect returns that are higher than what they can generate by investing in individual pure plays.

E&P companies will not transform into pure plays overnight. They will need to think carefully about which pathway(s) makes the most sense—operationally and financially. NOCs, IOCs, and independents across different geographies will have different incentives and motivations to transition or not. Their stakeholders, whether governments or individual investors, will want returns commensurate with the risk they are assuming.

The Case for Specialization

Gone are the days when subsurface insights ruled the E&P world. Until recently, subsurface knowledge was closely guarded. It was viewed as the key to unlocking tremendous enterprise value.

Moving forward, enterprise value will come from the efficient and effective monetization of those reserves that make economic sense at the prevailing commodity prices. So how can E&P companies make this happen?

A look at the value-chain evolutions of other capital-intensive industries such as automotive, heavy machinery, and aerospace provides the answer. Each of them witnessed a greater degree of specialization emerge in all parts of their value chains. The need to specialize over time is the recurrent theme. The same will likely happen in the O&G industry. Actually, it already has. It was the need for specialization that led to the creation of upstream, midstream, and downstream businesses. Now, that trend is poised to continue its natural progression with the split of upstream businesses into their constituent value-chain elements.

The three upstream value-chain pathways—development, production, and marketing—have very different risk-reward profiles. So different, in fact, that there is no good reason for these functions to be commingled into one amorphous business. When a specialist company assumes sole responsibility for managing a given value-chain element, it is safe to assume that every inefficiency will be squeezed out. That is when returns, commensurate with the risk being undertaken, start growing. For example, E&P companies that follow the marketers’ pathway (think commodity traders) may be compensated more because they take market risk and decide on when to build crude inventory and when to draw it down and sell it.

What is needed, then, for this environment of upstream specialization to materialize? First and foremost, transparency into every aspect of operations, along with the quick and efficient disseminations of insights for better decision making. Isn’t that what digitization is all about? Digital technologies and advanced analytics will enable companies to accelerate their transitions to a specialized model. A vision for specialization, coupled with new enabling tools, will give the O&G industry a new lease on life.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this document are meant to stimulate thought and discussion. As each business has unique requirements and objectives, these ideas should not be viewed as professional advice from Accenture with respect to the business.

Manas Satapathy is a managing director with Accenture Strategy & Consulting. With more than 20 years of experience, he works with many of the largest oil and gas, mining, and oilfield services companies to formulate and implement strategies and investment initiatives. He has authored several thought pieces in Petroleum Economist and Energy Perspectives on the evolution of global crude-oil and natural-gas landscapes.

Herve Wilczynski is a managing director with Accenture Strategy & Consulting and the global lead for Energy Upstream. Over the past 30 years, he had held senior positions with Fortune 500 companies and management consulting firms. He routinely works with oil and gas companies around the world on strategic and operational issues. His experience includes portfolio strategy, operational transformations, technology innovation, and large-scale mergers and acquisitions.