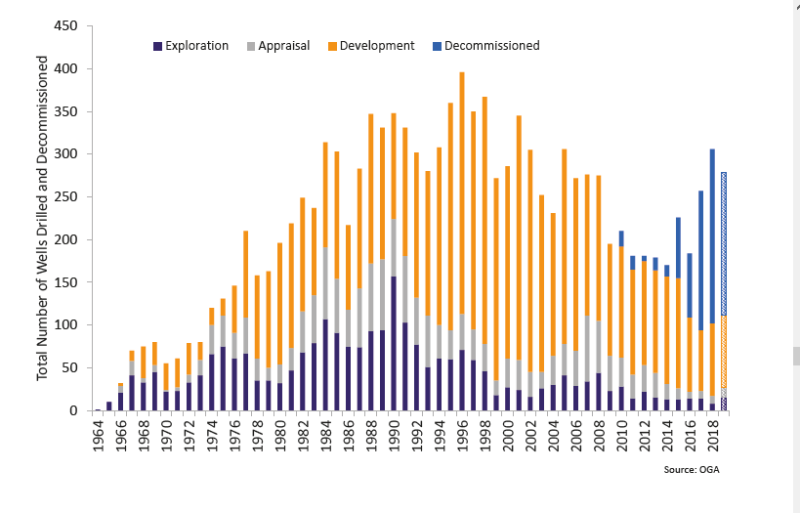

For a second year in a row, the number of wells decommissioned in the UK North Sea outnumbered the wells drilled to find and develop fields, according to the 2019 Business Outlook from Oil & Gas UK.

Despite this tilt toward plugging and abandoning older wells, production gains this year are again likely to be near 4%.

One reason decommissioning looms so large is that only eight exploration wells were drilled in 2018—the first year with less than 10 since 1965, when commercial volumes of oil were first discovered in the UK North Sea.

But this small investment yielded big returns—nearly 500 million BOE discovered, based on preliminary estimates of four discovery wells, according to the outlook.

The outlook in the UK is a case study of the squeeze facing exploration and production in other basins where operators are trying to pay to sustain production with discoveries, while plugging and abandoning old wells, all paid for by the lean cash flow due to low oil prices.

UK decommissioning spending is expected to peak in 2019 at $1.9 billion in 2019. It is on the leading edge of a rising global wave of decommissioning, according to a recent report by Rystad Energy,

“In 2013 and 2014, when oil prices where high, very few operators initiated plans to decommission older assets. Instead, they sought to maximize returns from their producing assets,” said Audun Martinsen, a Rystad Energy partner. After the oil price dropped in 2014, funding for projects to revive older fields disappeared.

“Although oil prices have recovered to more sustainable levels, the elusive $100/bbl still seems like a distant dream for most operators. As a result, numerous operators have begun realizing their obligations to decommission elderly, uncompetitive assets,” he said.

While other regions are looking ahead to shutting down a growing number of wells, the UK is trying to limit the cost, which is crowding out spending on finding and producing new fields. The industry is focusing on extending the life of older fields, and limiting the cost when wells must be decommissioned.

As a result, the outlook predicts the annual cost will drop to an average $1.5 billion through 2027. The study estimates that improving methods are reducing decommissioning costs, with a 7% decrease from 2017 to 2018. It reports the government is considering how to establish the UK as a “center of decommissioning expertise” to further the expertise it has developed at a time when global demand for these skills is likely to grow.

The blue bars show the strong growth in the number of wells decommissioned, which easily exceed the number drilled to find and develop new reserves. Source: Oil & Gas UK 2019 Business Outlook.

Hungry for Hits

Decommissioning has provided work for service providers during a deep slump, but it has absorbed resources needed to find more oil and gas at a time when domestic production is supplying a shrinking percentage of the UK’s energy needs.

One plus is the asset sales are putting some older fields in the hands of operators who are more inclined to find ways to eke out more oil to extend the life of these fields, but that can only slow the decline.

Growth will depend on those exploring for new fields. Last year, the number of wells drilled was historically low, but those operators got lucky.

At the time the outlook was written, results from six wells were in and four of them resulted in discoveries holding up to 485 million BOE of oil and gas, based on the initial estimates of what might be producible.

More than half of it was in Glengorm, a high-pressure/high-temperature discovery made in the central North Sea by CNOOC.

Explorers benefited from advanced seismic imaging in near production facilities where the geology is well understood, the report said. The proximity also reduced the time between discoveries and production. Apache managed to begin producing from its Garten field discovery in 8 months.

But, the report warned that “production cannot be sustained in the long term if drilling and wells activity remains low.”

The odds do not favor such big payoffs on such small exploration bets. The report points out that 20 more exploration wells were drilled offshore Norway to discover about the same volume of oil. Maintaining such a large edge, with comparable companies working in similar, mature basins, will be tough.

This year, drilling is expected to begin on 15 exploration wells in UK waters, including some “high-impact prospects” that could open up new plays, the outlook said. One of those is the Northern Gas Area west of the Shetland Islands, where a discovery at the “Lyon” well could justify construction of a gas hub allowing development of small discoveries nearby.

Development drilling, though, is once again to total about 85 wells, and is not likely to rise in the near term. The number of barrels added per development well drilled has been far greater than in the past. From 2014 to 2018 the number of development wells drilled was one-third of what it had been, but production has been rising.

Some of the productivity gains are sustainable. “Production has been supported by improvements in facilities, infrastructure, and reservoir optimization,” the report said. New drilling techniques allowed companies to reduce the number of wells required. For example, the Catcher field in the North Sea was developed using 18 wells, which is expected to result in the same recovery level as 22 wells.

Lower Cost/Barrel

Rising production over the past 5 years has reduced the cost of producing a barrel of oil, or its energy-equivalent of gas, from $15.30/BOE in 2014 to $11.40/BOE. This reflects rising production—the total is up by 20% since 2014—and a focus on reducing the cost of every aspect of exploration and production.

“Companies are looking to sustain recent cost reductions and will not allow unit operating costs (cost/BOE produced) to increase,” the report said.

Rising oil and gas prices improved cash flow for UK operators last year, but “budgets remain tight.”

One risk factor is a decline in the service sector, which has been a strength in this mature basin.

“There has been significant pressure on the supply chain in recent years. Drilling contractors have been amongst the most affected” due to reduced drilling, the report said. As a result, it said “a loss of capacity and resources within the drilling sector is a real threat to the ability of industry to meet any increase in drilling activity in a sustainable manner.” It predicted a tightening in the UK rig market this year as exploration drilling is expected to double.

On the plus side for the service sector, after years of capital spending declines, this may be the first year where service providers see an increase, though a small one.

Future budgets will remain tight. Oil and Gas UK formed a Well Forum to find and implement ways to reduce the cost of drilling and make the wells produced more productive.

The Oil & Gas Technology Centre in Aberdeen is working on developing new methods to increase the productivity and reduce costs by deploying new digital technology, extending the life of old assets, finding ways to develop marginal discoveries, and lowering the cost of decommissioning.