The biggest unconventional oil producers have revolutionized global oil markets and driven down prices. Still on the list of things to do: consistently make strong profits.

By the next decade, they might, according to a report by Wood Mackenzie, which predicts that margins will grow for the biggest, most efficient independents beginning around 2020.

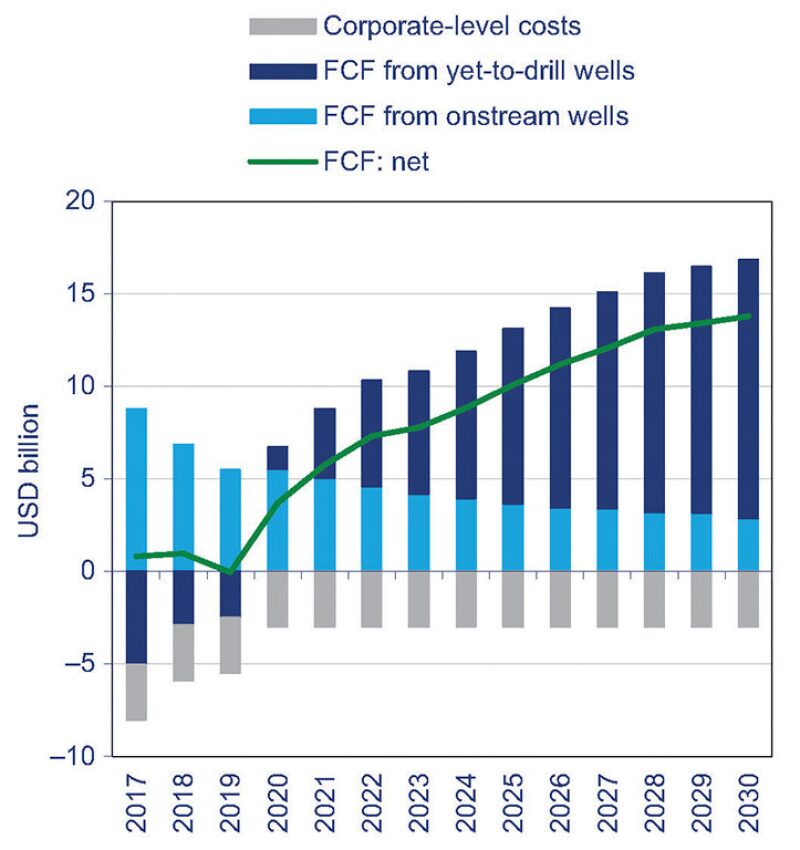

The actual prediction is “the five leading tight-oil specialists will start to deliver significant positive free cash flow in 3 years’ time, based on our $66/bbl Brent oil price assumption for 2020.”

Which would mean that five companies whose business depends on producing liquids and gas from ultra-tight formations—Continental, Devon, EOG, Newfield, and Pioneer—would begin generating considerably more cash than they are spending to produce far more barrels of oil per day than they are now.

“They will be transitioning out of the capital-intensive phase and moving into the harvest phase” as these enormous, long-term developments reach critical mass, said Benjamin Shattuck, principal upstream analyst for Wood Mackenzie, who was part of the team that produced the recent report: When Will Tight Oil Make Money?

The timing reflects the number of years the energy information and consulting firm expects it will take for oil demand to catch up with supply—resulting in higher oil prices—and also when the number of producing wells will reach the level where the investment required to sustain and expand production goes down.

But oil price predictions are notoriously unreliable, even if the prediction is for a month out. A big variable will be continued support from investors who have made it possible to add millions of barrels a day of oil production by investing $33 billion in the long-term growth plans of these companies.

By 2020, Wood Mackenzie is expecting these companies to be shifting their focus to balance growth with consistently rising profits. While the report shows they now have the cash flow to sustain operations, the goal is to earn considerably larger amounts of money to provide a payoff for the tens of billions of dollars invested in building the business.

Failure to downshift the growth engine could have serious negative consequences.

“The myopia of a sector focused on growth means our 2020 vision of surging cash flow could quickly become a mirage” because investors lose hope that oil prices as well as profits will rise, the report said.

The coming years will also weed out those companies that are not strong. Winners will range from majors that exploit their ability to do technically challenging projects to small companies with a nimble, innovative, cost-cutting culture.

“We do not believe every company will reach profitability,” Shattuck said, adding, “but the good tight-oil operators are poised to weather the risk.”

Bulking Up

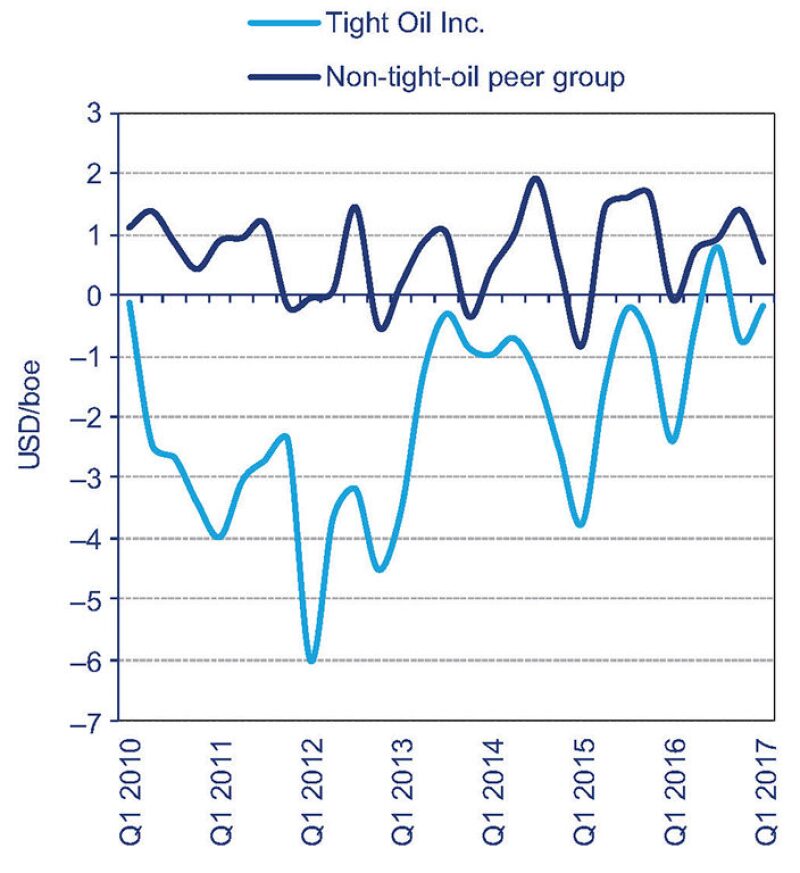

While this group of tight-oil producers is still short of being consistently cash-flow positive, the gap has narrowed between Wood Mackenzie’s tight-oil-focused companies and peers in other sectors. Over the past 12 months, they have been moving into positive territory. That is due in part to cost cutting since 2014, with producers squeezing discounts from suppliers. They also have focused on finding more efficient methods and targeting the most productive spots to drill and fracture.

While competitors outside of tight oil have focused on similar goals, their cash flow has remained within the same range.

Those working in unconventional formations have more room for improvement and potential for growth. These formations also cover huge areas, with opportunities magnified by the number of layers available to exploit, allowing production growth for decades without the risk of drilling a discovery well.

“Led by the Permian, tight oil’s huge inventory of undrilled wells allows operators to recycle free cash flow from producing wells immediately into new, low, break-even wells that generate similar, attractive returns,” the Wood Mackenzie report said. In comparison, conventional exploration requires “sporadic, lumpy and large-scale investment decisions.”

By 2020, larger tight-oil operators will have developed enough producing wells that the cash they generate will support the operation. Studies by Total have concluded that a diversified portfolio of producing wells of various vintages reduces the drilling rigs needed to sustain or expand output.

Simulations run on Total’s software show that large developments made up of wells that rapidly decline in their early years behave quite differently as a group over time. As more wells are added, the production volatility is reduced because the fast-declining recent wells are balanced by the steadier output from the many older wells. It works like a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds.

This means that “the more you feed” the asset base by adding wells, the less drilling is required to sustain or add production, said Philippe Charlez, a senior technology advisor for Total, during a presentation at a recent oil and gas conference.

“Even if there is a big change in price, production will resist the change. Production strongly resists a drop in working rigs,” Charlez said.

That muted reaction gives operators the flexibly to turn spending on and off as prices fluctuate, without killing production. Those operators also move money to the lowest-cost play, which is the Permian, while reducing activity in higher-cost areas, such as the Bakken, where a small number of rigs working has been able to mute the decline.

Faster drilling, or more productive wells, further reduces the number of drilling rigs required, he said. And this year, gains have been required to help offset the rising cost of labor and services.

The large amount of energy, water, sand, and chemicals required to get oil out of tight rocks means that there is a strong relationship between costs and the value of assets. Wood Mackenzie said a 30% increase in development-capital costs will lead to a 30% fall in company asset value.

When predicting the future, technology is “a big wild card.” While Wood Mackenzie expects that productivity gains could be “more limited than in the recent past,” a breakthrough, like proving that natural gas injections can increase ultimate recovery rates well past 10%, could have a large impact on the economics of the business.

Another change, which was outside the scope of the report, was the large and growing presence of major oil companies in the Permian. While they are late to the shale business, their financial muscle and technical skills may give them an edge in managing complex, long-term projects demanding huge investments, Shattuck said.

Price Worries

The biggest barrier to profitability for tight oil producers has been their prolific production growth. As a result of a lingering oil glut between now and 2020, Wood Mackenzie and Charlez see prices fluctuating in a band around $50/bbl during this decade.

By 2020, Wood Mackenzie expects that world demand will exceed what US unconventional producers can supply and deep exploration cuts in places such as deep water, will have stymied growth elsewhere.

Wood Mackenzie acknowledges that slowing down would represent a break from the strategy that has been the norm for US shale producers, which have built aggressive growth targets into the formulas used for setting executive compensation.

For now, production growth remains “the principal metric by which Tight Oil Inc. is measured and rated by the market.” And by its calculation, the greatest long-term payoff is produced by drilling now rather than slowing down to generate greater cash flow. But by 2020, it expects the investors who have provided the billions that fueled growth will begin pressuring operators to begin managing growth to deliver a greater return.

How companies “manage the transition to lower operational growth beyond 2020 and returns to shareholders (including dividends) will be important concerns for investors looking to see evidence of capital discipline,” the report said.