In 2015 when the declining UK North Sea offshore sector was sinking into a deeper slump, the head of an industry task force set up to find ways to make the sector more efficient said, “We have got to get about 40% out of our cost base really, really quickly.”

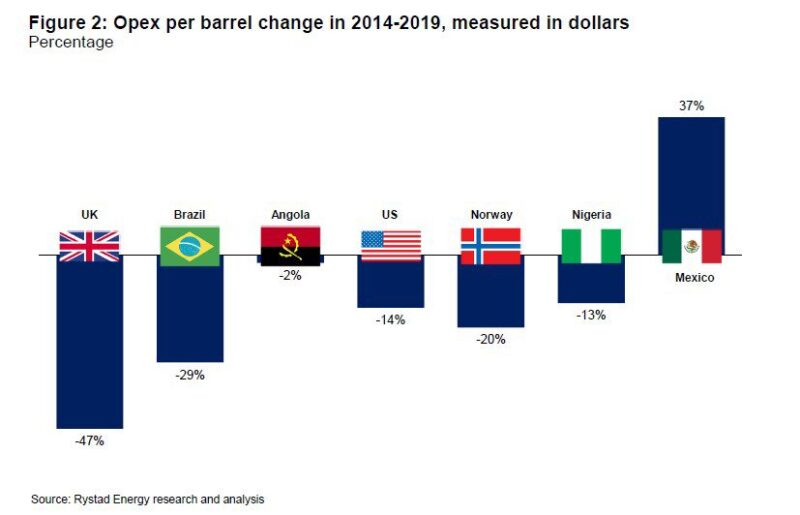

Five years later, Rystad Energy released a report showing that over that time frame the UK hit that target, leading the world’s offshore markets in cost reduction.

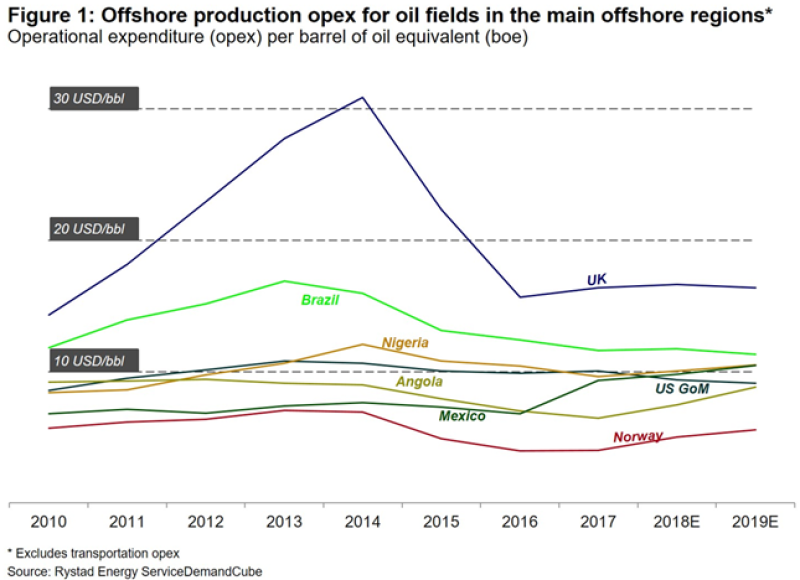

“The UK has experienced the greatest reduction in Opex/BOE, falling from more than $30/bbl in 2014 to just $16/bbl in 2019,” said Sara Sottilotta, an oilfield service analyst at Rystad Energy.

Reduced costs per barrel in the UK reflect rising production from new developments, allowing them to spread costs over more barrels and reducing the share of production from higher-cost older fields, she said.

UK offshore remains the most expensive region in the world, but the price gap per barrel has narrowed from $10–20/bbl to $5–10 bbl. Workers also contributed to the savings, with lower pay and longer rotations—working 3 weeks rather than 2 weeks at a time—and lowered transport costs.

As a result, exploration and development of old and new fields has allowed UK oil and gas production to rise by 20% from 2014 to 2018. That represented a striking trend change after 14 years of steady production declines, according to the 2019 annual report from the industry group, Oil & Gas UK.

Much of that growth was due to the development of discoveries made before 2015, when $100/bbl oil encouraged exploration in the face of high costs.

Continued growth in the 2020s will depend on continued high levels of exploration success on a small number of wells drilled. In 2018 only eight exploration wells were drilled, which was the lowest since the birth of the UK North Sea offshore industry.

Luckily, six of those wells delivered significant discoveries. The estimates of oil and some gas in the ground from those wells has been equal to 78% of the produced volumes that year, and not all the results are in. The Oil & Gas UK report said it is a strong result for the number of wells drilled, but still leads to a projection of flat to reduced levels of production ahead.

That will depend on the results of the 16 exploration wells expected this year, and the ability of the industry to find ways to compensate for the inevitable price increases in services as the global offshore business slowly comes back.

Day rates for high-performance drilling rigs are already rising, the report said.

Labor costs are also likely to rise. Rystad said UK workers contributed to the savings by agreeing to lower pay and longer rotations. When conditions improve, unions will demand that workers be compensated for past sacrifices.

Making matters harder, the potential production, according to the UK regulator, is not much higher than the largest fields recently discovered in Brazil. Getting the last oil out will require high-cost activities such as extending the life of older platforms, tapping small, remaining deposits, and decommissioning nonproducing fields.

Cost savings were also the product of measures encouraged by the Oil and Gas UK Efficiency Task Force such as more efficient maintenance, innovation, and better planning, Rystad said.

From the outside, it is impossible to estimate the value of sustainable changes, such as using simplified, standard designs, or whether the savings are a product of tough negotiations and deferred maintenance spending.

“In times of downturn, some Opex reduction has historically been a consequence of maintenance deferral,” leading to costly downtime later, Sottilotta said.