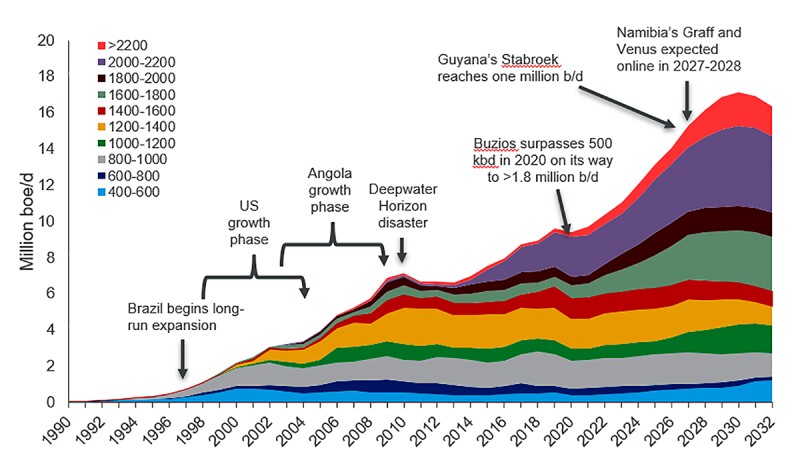

Deepwater production globally is expected to increase by 60% by 2030, according to Wood Mackenzie.

“Deepwater is the fastest-growing oil and gas resource theme,” said Marcelo de Assis, director of upstream research for Wood Mackenzie. “Brazil, Guyana, and Mozambique are the main growth drivers. Developments are also getting deeper; production from water depths of over 1500 m will surpass that from 400 to 1500 m by 2024.”

All of which is good for suppliers. Through the first 10 months of the year orders for subsea trees were up 51%, according to Westwood Energy.

The growth in production technology required, though, is up significantly. This is the decade where fields in water depths of 2200 m (7,200+ ft) have become significant.

Deepwater’s steep climb is in sharp contrast to most other oil and gas plays. While conventional onshore and unconventional gas will be rising through 2028, all other categories are expected to be flat to down through the period.

That means that supplies of oil and gas are not rising much overall because deepwater’s share of global production remains fairly small, rising to 8% by the end of the decade from 6% currently.

Deepwater production additions, which will push it to 7 million BOE/D, are a lagging indicator of discoveries made years ago, and the rate of discoveries this decade is lagging far behind those years.

The Wood Mackenzie growth chart peaks at the end of this decade and curves down from there. Less production is likely because of the drop in exploration spending this decade to “near all-time lows” this year, according to a recent report by Rystad Energy.

“Global exploration activity has been on a downward trend in recent years, even before the COVID-19 pandemic and oil market crash, and that looks set to continue this year and beyond,” said Aatisha Mahajan, vice president of analysis, Rystad Energy.

It attributed the drop to oil companies focusing their spending on developing proven reserves, as well as a decline on offshore properties available as some key countries, including the US, reduce the number of lease sales due to the pressure to phase out oil and gas production.

While Wood Mackenzie’s chart predicts slowing production, the report said forecast “remains uncertain.” But odds against continued growth next decade would seem long.

“We could see production performance begin to peak and then plateau after 2030 without an exploration and investment renaissance,” de Assis said.

Another negative is already slowing development—rising costs.

“In some regions deepwater rig costs have doubled compared to 2021 day rates. It has hit global hotspots such as the US GOM and Brazil hardest. Gato do Mato in the Brazilian pre-salt, for example, will be delayed by up to 2 years due to rising costs,” the Wood Mackenzie report said.

“Constraints in the global deepwater supply chain will, with time, increase lead times and unit costs across the board,” it added.

Despite years of changes that lowered the cost of drilling and development, “the hard-fought efficiency gains made during previous downturns are starting to reverse.”

The Big Eight

Deepwater remains a domain dominated by seven major international companies plus Petrobras. This group accounts for 65% of the deepwater production and a similar share of the projects, Wood Mackenzie said.

“The future of the deepwater sector remains in the hands of the majors and Brazil’s Petrobras for the foreseeable future,” de Assis said.

Petrobras is the biggest among them by far, with a deepwater portfolio twice as large as the second company on the list, Shell.

To help pay for its large development and exploration programs, the Brazilian national oil company has been selling off older properties to midcap-size oil companies entering that offshore market.

“We will see a significant shift in Brazil’s production makeup. In 2015, Petrobras held 84% of all production. That level will drop to 61% by 2030, as the majors’ and the independent operators’ output grows,” said Amanda Bandeira, Latin America upstream analyst for Wood Mackenzie.

These newcomers are expected to make $10 billion worth of capital investments in the coming years, which is expected to add 485,000 BOE/D by 2027, and then decline from that peak, according to a Wood Mackenzie report. Some companies are preparing for that change.

“We already see some moves to bolster the longer-term outlooks through M&A and exploration. Late-life asset optimization will also be a focus, to maximize the operational life of their mature asset portfolios,” said Vinicius Diniz Moraes, Latin America upstream analyst for Wood Mackenzie.