The EU has agreed to an immediate ban on seaborne imports of Russian oil and oil products, representing two-thirds of Europe’s total purchases from Moscow. While the decision temporarily allows pipeline imports of crude, those too will eventually be phased out, with Germany and Poland pledging to do so by yearend.

European Council President Charles Michel announced the ban in a late-night tweet on 30 May, the first day of a 2-day extraordinary meeting of European leaders in Brussels to address energy and food security. The next day the European Commission, which executes policy decided by the council, clarified that the embargo will be phased in over 6 months, and the ban on refined products will have an 8-month delay.

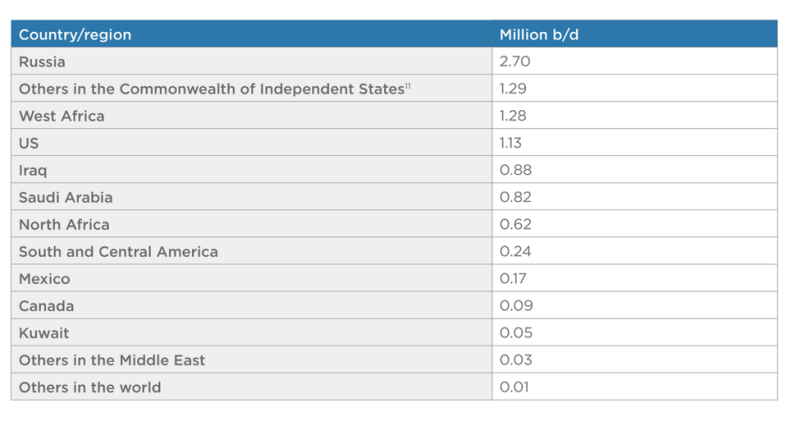

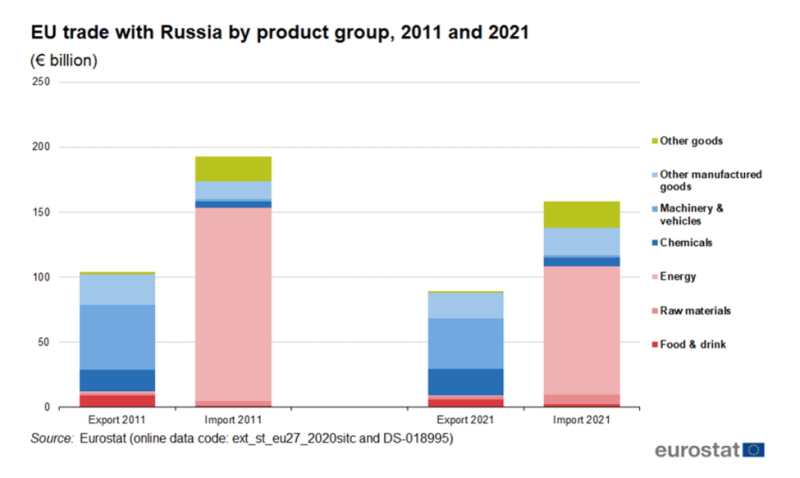

Russia provided nearly 30% of Europe’s crude oil imports prior to the conflict in Ukraine and was Europe’s largest supplier, sending nearly 2.5 times as much crude to EU member states as its nearest competitor, according to BP’s Statistical Review of World Energy. The New York Times estimated that Europe has been paying Russia $23 billion a month for those supplies.

The ban, contained in the sixth package of sanctions issued by the EU against Russia since the Ukrainian conflict began, includes what the European Council calls a “temporary exception for crude oil delivered by pipeline.”

The exception was agreed to obtain buy-in from EU members, particularly Hungary which is landlocked and depends on Russian crude delivered via the southern leg of the Druzhba pipeline that transits Ukraine. Slovakia and the Czech Republic are similarly landlocked and dependent on the same Soviet-era Druzhba system.

Argus Media quoted the Netherlands Prime Minister Mark Rutte as saying that EU leaders will decide later as a "technical issue" how long the pipeline exemption will last because it is intended to give affected countries time to adapt their refineries.

European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen told reporters covering the summit that Germany and Poland have pledged to end Russian crude imports through the northern leg of the Druzhba which transits Belarus by the end of this year. At that point 90% of Russian oil imports to Europe will have been eliminated and EU leaders can then assess how to handle the remaining 10%.

If Russian supplies transiting Ukraine by pipeline are disrupted, the EU will allow Hungary, Slovakia, and the Czech Republic to import Russian oil supplied by tanker through a third country.

Along with Russian oil and oil product imports, new EU sanctions also target insurance and reinsurance for Russian ships; bar EU companies from providing Russian firms with various business services; and exclude Russia’s largest bank, Sberbank, from the SWIFT international interbank transfer system.

A recent study by the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University in New York noted that Europe will have problems finding suppliers to offset the 2.7 million B/D of Russian oil it imported in 2020.

While the US could increase oil exports to Europe, the light, sweet grades of crude the US produces are not suited for European refineries which are designed to refine Russia’s sour Urals blend. Venezuelan heavy crude would be suitable, but like Russia, the country’s oil and gas industry has likewise been hobbled by sanctions.

Most likely, Europe will turn to the Middle East and buy more from traditional suppliers such as Saudi Arabia, Iraq, UAE, and Kuwait, the Columbia University think tank argued.

This is already happening. The Suez Canal Authority reported tanker traffic at historic highs in April, driven by Europe’s demand for more Middle East energy.

As to where Russia will redirect oil exports usually destined for Europe, China and India are the obvious buyers, and with Russia offering deep discounts, both countries have been purchasing Russian crude at record levels. Transport though has been a problem as shipping companies are often unable to find insurance or otherwise fear reputational damage.