When oil demand vaporized, oil sands producers quickly had to cut 1 million B/D of production.

“Our strategy is to keep as many barrels away from the train wreck as possible to minimize negative cash margins,” said Rob Peabody, chief executive officer for Husky, during a call with analysts.

Now that oil prices are back near the levels where oil sands producers can consider restarting them, it is time to answer the question: “Can they turn them off and on?” said Scott Norlin, a research associate at Wood Mackenzie.

Executives with major oil sands companies said they can turn them off and on without missing a beat based on lessons learned from big cuts in recent years.

“So, will there be some impact? Maybe, but very little,” said Tim McKay, president of Canadian Natural Resources Ltd. (CNRL), during its first-quarter earnings call. “We've been very strategic in how we reduce our production. So, turning our wells down, not necessarily off, and keeping that oil going into a tank. I think from our perspective, it will have no impact.”

They were not saying there are no risks associated with turning down the heat that drives steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) production—steam injected by of a horizontal well to heat ultraheavy oil, allowing gravity to pull it down to a production well.

There were also reductions at surface mines, which present a different set of issues not covered here.

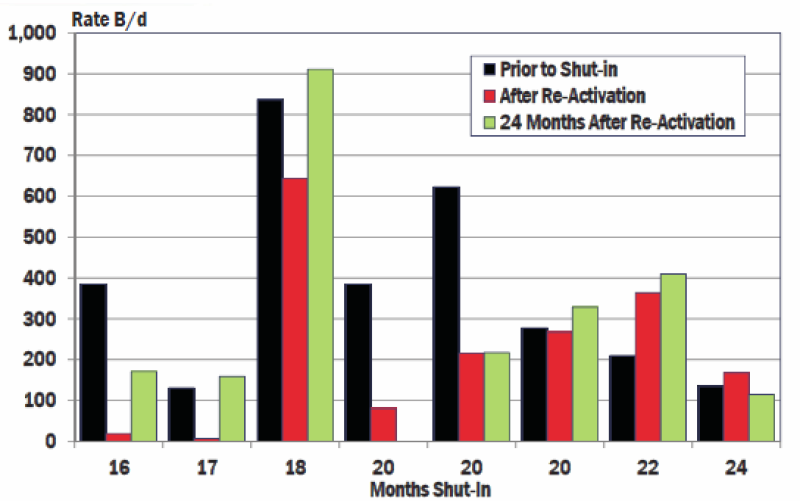

A long-time oil sands engineer discovered the results were mixed after a long shut-in. A couple years after the restart, some well pairs produced more and others less.

It was hard for Bruce Carey, a research associate at Peters & Co., to come to firm conclusions because the data were limited. He started with 1,700 well pairs with shut-ins and ended with only 44 that fit all the criteria, which included at least 6 months offline and 2 years of production data afterward. After eliminating well pairs with data quality problems or operational change, only 8 that had been shut in for more than 15 months were left.

“The SAGD industry has limited operational experience with long-term and widespread shut-ins and reactivations of SAGD wells and virtually no published technical analyses,” wrote Carey in a 2016 report.

The data combined with detailed well information, though, helped explain performance differences and the need for alternatives to completely shutting down steam injections.

Since then the industry has learned a lot more about what happens when wells are turned off. Forest fires back in May 2016 required a cluster of major oil sands projects to close for 4 or 5 months. That was followed by reductions required by Alberta regulators during a period when production exceeded pipeline capacity.

“I'll remind you that we've got quite a bit of experience of this, sadly, from both the 2016 Fort McMurray fires and then from the time of curtailment management,” McKay said.

Based on what he’s seen over the past 4 years, Carey wrote an analysis this year about current risk management methods.

“Based on past shut-in data, at least 20% of Alberta’s SAGD production could be shut in for an extended period (on the order of a year) with an acceptably low level of potential risk of harm to future production,” Carey said. That proved to be in line with actual reductions in SAGD production, which dropped from 1.5 million B/D in January to 1.2 million B/D in May, he said.

The performance of 8 well pairs with more than 15 months of being shut in showed a nearly even mix of results. Source: Peters & Co. Ltd., geoSCOUT.

Why Worry?

One obvious conclusion in Carey’s 2016 study: Even when heavy-oil prices were way down, operators were reluctant to stop production for long.

There are economic arguments for that, and there was a horror story. Norlin, who was an oil sands geologist before becoming an analyst, recalled a project called Great Divide.

It was a small project from early this century that was shut in in 2008 for economic reasons and again in 2016, known for serious restart problems and a 2,000 B/D production drop to 14,000 B/D after the second shut-in.

As a result, people in the industry wondered if they shut in a well “will that happen to me? There has been resistance to it,” he said.

This year’s cuts are a massive test of what has been learned using less steam, or in some cases none at all, to maintain the steam chamber—the heated productive area above the injection well.

The label “steam chamber” is a misleading—this is highly porous rock rich in ultrathick crude—and multiple chambers can develop along the mile-long injection well.

Well risks vary based on the age of the well. Older wells are less risky because years of steam injections have heated a large area that cools slower than in young wells, where the steam chamber is still developing. The wells in between those ages are tricky.

The danger of steam chamber collapse is magnified if there is water near the top or the bottom of the zone. When water comes in contact with the chamber, reduced steam injection can allow the formation to cool and a drop in pressure to occur, allowing an influx that quenches the hot rock.

To minimize the risk, the industry has moved from simply shutting off injections to slowing them or replacing the steam with a gas that will not condense, most often natural gas, to maintain a high enough temperature and pressure to preserve what took years to create.

A lot of approaches are being tried. “It’s a mix, probably with more emphasis on slowing injection and production,” Carey said. He said they are based on the “generally good idea to just turn down injection production if you can.”

The Payoff Is?

Even if engineers figure out how to reliably slow down wells so they will come back producing about as much as they did before shut-in and using about the same amount of steam per barrel of oil, that doesn’t mean slowing down is the financially smart reaction to a price drop.

The industry has had economic reasons for being reluctant to slow down production when prices plunge. An obvious problem are the long-term contracts to supply refiners.

There is also the financial principle that a dollar earned now is worth more than one in the future. This consideration looms large in projects built to tap formations holding decades worth of oil. The output of a SAGD well is a function of how much steam can be generated. A big jump in production would require a significant investment in wells and the thermal infrastructure to support them.

Now natural gas prices are cheap, so sustaining steam injections is not costly. And a handful of big, mostly Canadian, oil sands operators have invested billions in facilities to upgrade or refine low-value ultraheavy crude into higher-value products, allowing them to profit on bitumen when the raw material price is down.

Most US shale producers are surviving by using hedging to lock in prices for oil and gas that exceed the current low market value.

When Norlin looked into hedging by big oil sands companies, he found little to study. “Their hedges are their downstream operations,” he said.

The plunge of oil demand this time forced oil sands producers to cut production. But ConocoPhillips has argued that production cuts when prices are depressed can be a money-making opportunity.

The strategy is a like storing oil when prices are down and waiting for a price increase without the expenses associated with producing and storing that oil.

Big curtailments when prices are low are a “quasi-investment,” said Ryan Lance, ConocoPhillips chairman and chief executive officer, in an interview with Daniel Yergin, vice chairman of IHS Markit.

The strategy, which was explained in this presentation to a major investment bank, assumes the barrels not produced during a slowdown can be made up in the future when prices are higher.

“It does take years to make up all that production … presumably you will be producing it as a much higher price,” Lance said.

That can be done relatively easily in shale. Just speed the pace of drilling when prices rise.

Production from thermal projects is based on the amount of steam injected and that volume is limited by the steam-generating capacity.

Turning wells down when prices are low in hopes of turning up the production and profits when prices rise requires confronting two unsolved problems—accurately predicting oil prices and finding a way to sharply increase the capacity limit on SAGD wells without a big investment.

Short Break?

When Fox of ConocoPhillips was asked why the company is confident they can turn these wells back on without trouble, he said, “We go through this on a regular basis in our fields anyway, just for a shorter duration.”

The duration of slowdowns, many of which began in April or May, may not be much longer than an extended turnaround.

With the price of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate flirting around $40—near the breakeven for oil sands producers—some of those interruptions might not be much longer than a maintenance project.

ConocoPhillips is in “the process of thinking about under what circumstance should we start coming back into the market,” Lance said.

The argument against a mass restart is “everybody in this space is having this conversation,” he said. OPEC has been talking about when to reduce its cuts, and US shale producers expect to have restarted most of their shut-in wells by this this fall. But all of them know that demand is coming back slowly and is likely to be end lower in 2020 than it started.

Norlin sees SAGD producers keeping a close eye on prices as they cautiously add production. Because of recently completed expansion projects, if the economics allow it, “the expectation is that oil sands actually will grow in 2021. There are enough projects that had just finished expansion … this was supposed to be a big year,” he said.