Good housekeeping has proven to be a big difference-maker for Houston-based Callon Petroleum.

The independent shale producer recently published a study showing how it developed a data-driven workflow to predict which wells will suffer the most screenouts, allowing them to build in time for a preventive completion practice known as a clean sweep.

“It’s not a new concept. It’s not a fancy technology,” said Nancy Zakhour, a completions engineer with Callon who worked on the study. “It’s just us trying to better understand which differences made to our operations are impacting production and whether or not we can leverage that to our advantage.”

The company attributes its approach to clean sweeps to better proppant placement and higher production. While supporting figures have not been disclosed, Zakhour emphasized, “We came to know that whatever we did with the sweep enhanced the wells’ productivity.”

Her confidence in the effectiveness of the clean sweeps is partly backed by hydraulic fracturing models that indicated that the fracture designs themselves were not the chief driver of well performance. Run post-completion, Zakhour said the models showed how the clean sweeps were allowing otherwise inactive perforations to be successfully “pumped to completion” with a full dosage of sand.

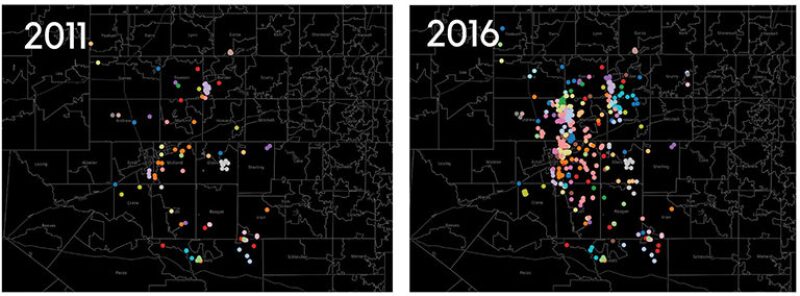

This work was done through Callon’s Spraberry Trend program in the Permian Basin in west Texas and involved geomechanical data from the drilling of eight wells and pressure data from 145 fracture stages. The project’s details are in a technical paper (SPE 184843) that was presented in January at the SPE Hydraulic Fracturing Technical Conference in The Woodlands, Texas.

Typically done after an individual fracture stage is stimulated, a clean sweep involves pumping full-wellbore volumes of water downhole to return any loose proppant, or in this case sand, back to the surface. By comparison, a dirty sweep is when sand concentrations are reduced temporarily before the pumping ramps back up again.

Ironically, dirty sweeps are done to save time but Callon’s analysis proved that they were causing too much sand to settle near the perforation clusters, leading to a high number of screenouts—a problem that happens when the sand moving into open perforations gets jammed up just like a crowd of people would if they tried to pass through the same door all at once.

Per industry reports, a single screenout requiring coiled tubing remediation may cost USD 80,000, and it is not uncommon to suffer several of them in the course of a single horizontal well completion.

Working the Data

Callon carried out this research project last year with service provider Sanjel Corporation. Engineers from both companies were able to realize the importance of the clean sweeps, along with other key learnings, using an in-house-developed algorithm to quickly analyze the rate of penetration, gamma ray logs taken during drilling, and rock stiffness (Young’s modulus).

Olubiyi Olaoye, who worked as a completions engineer with Sanjel until the company’s restructuring, said the algorithm categorized the project’s eight wells into three types. Above all else, the most defining factor between the well types was the properties of the rock in which they were landed, highlighting that geology and geomechanics are powerful dictators of how a completion design performs.

“One thing we knew before the completion jobs even began was that these wells were different in terms of what we saw when they were drilled,” Olaoye said. “Based on that knowledge, we went into the project thinking we were going to treat them all the same, even though we knew that they were different, in order to see the responses on three different types of wells.”

This scientific approach paid off and proved that each well type needed its own completion strategy with regards to the number of clean sweeps, sand grain size, and acid treatments.

For instance, Type 1 wells had a 74% chance of requiring at least one clean sweep while Type 2 wells had only a 15% probability. Knowing this gave the completions team the ability to schedule a sweep into their operations rather than stopping work to deal with it unexpectedly.

Additionally, the engineers looked at each well type’s gamma ray resistivity to determine the calcium carbonate content. Olaoye said wells with higher calcium carbonate benefited the most from a pretreatment of acid which increased the flow area around the perforations.

The analysis also showed that the well type with the stiffest rock benefited the most from using an initial slug of fine- grain sand (100 mesh) to clear out the perforation area before pumping the larger sand for the rest of the stimulation.

May Not Apply

This new workflow may be useful to other Permian operators since so many of them have retreated to the Spraberry during the downturn due to it being shallower, and thus cheaper, to drill than the more well-known and prolific Wolfcamp Shale. However, the study’s authors also cautioned that the insights gained during this project are likely area-specific vs. play-specific.

They explained that being able to predict the need for clean sweeps will matter most to operators that are using slickwater fracturing fluids as opposed to gel-based fluids. With gel-based fluids a clean sweep is less critical since it has a higher viscosity, which will result in less leftover sand inside the wellbore.

Secondly, because the Spraberry is a relatively tight formation it requires a larger sand size (30/50 mesh) to hold open the fractures than do other Permian formations such as the Wolfcamp (100 mesh). The smaller the grain size, the easier it is for the formation to take it in, thus also reducing the propensity of screenouts.

And even if all these factors do apply, water availability could be a hard constraint to overcome as some wells will require two or three clean sweeps, which may add up to 20,000 bbl of additional water.