Shell has gotten approval to develop a North Sea gas project that had been previously rejected by British regulators.

The turnabout is evidence of a political shift in Britain where high gas prices have made offshore development a priority and reflects the results of re-engineering the project, which sharply reduced the offshore carbon emissions associated with a field that also will produce quite a bit of carbon dioxide (CO2).

This is a large step toward development of the Jackdaw field in the central North Sea that Shell said will deliver 6.5% of all the gas produced from the UK North Sea when it goes into service.

Clearly, government policies are now behind it. After the approval was announced, British business minister Kwasi Kwarteng tweeted, “We’re turbocharging renewables and nuclear, but we are also realistic about our energy needs now. Let's source more of the gas we need from British waters to protect energy security."

But it is not a done deal. It still requires a final investment decision by Shell and must get past any legal challenges by environmental groups which oppose field development. After the announcement Greenpeace said it was considering legal action.

Still, considering the effort by Shell the keep the project alive plus the support from regulators, the plan to put the field into production by late 2025 seems likely to happen.

That fact that a large field in the heart of the North Sea discovered in 2005 has not been developed is an indication of the challenges.

According to Shell’s revised development plan, “The fact that previous operators were unable to economically develop Jackdaw indicates the marginal nature of Jackdaw economics.”

While the potential production is promising, the engineering issues include high pressure (17,000 psi) and temperature (375°F), CO2 content averaging 4.2%, plus some hydrogen sulfide (H2S).

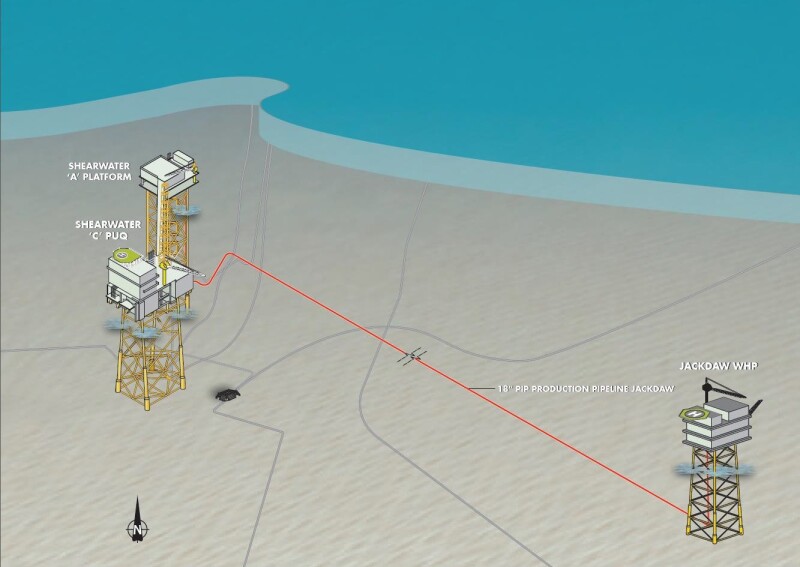

Shell’s plan saves the cost of a full-production platform by sending Jackdaw production from a planned wellhead platform via a subsea pipeline to the Shearwater platform designed to handle 410 MMcf/D of gas and 99,000 B/D of condensate from multiple fields.

This will extend the life of the large facility that regularly requires new sources of gas to replace declining nearby fields.

Shell has laid out a plan that will reduce the offshore emissions released over the field’s productive life by 43%, based on changes made in the scheme in the 5 months between the plan’s rejection and submission of the revised proposal in mid-March, a few weeks after the Russian invasion of Ukraine magnified gas supply worries.

Rather than releasing all the CO2 removed during processing, the new plan will send as much as possible to shore. The amount is limited by how much gas can be handled by a pipeline that was not built to stand up to concentrations of the corrosive gas.

Emissions will also be limited by focusing development on areas with lower CO2 concentrations of 6%.

These changes are not going to reduce the total carbon emissions unless Shell finds a way to pump it back into the ground.

This project has been described as a source of captured CO2 that will someday support Scotland’s push to become a hub for carbon capture and storage (CCS).

Pipelines will move the gas to Shell’s St Fergus gas plant near Peterhead, Scotland, where the remaining CO2 and H2S will be removed. It is also the onshore hub for Scotland’s CCS effort, known as Acorn, which is on indefinite hold since the UK government chose to fund a rival project far from the North Sea.

Using the gas for enhanced oil recovery was considered and rejected by Shell because it lacks a North Sea oil field with a platform able to accommodate all the equipment required to inject CO2 into the reservoir and remove it from the production stream of a suitable formation.

Making It Economic

The Jackdaw plan minimizes the need for new steel or added workers.

Production from the first four wells will flow up to a new wellhead platform which can accommodate nine wells. Corrosive-resistant materials will be used for pipes and other hardware coming in contact with the highly corrosive gas.

The structure will normally be unstaffed, according to the plan, and will be visited occasionally for inspections and repairs and have accommodations for 30 workers for projects.

Production, which will be controlled remotely, will flow 31 km to the Shearwater platform. Equipment there will be reconfigured to handle the high-pressure inflow as well as more than six times as much CO2.

To handle the high-pressure flows, the processing system will be divided into two. What was the test separator will process the high-pressure flow from Jackdaw, while the first-stage separator will handle the flow from lower-pressure reservoirs.

The amine separation units will be set up to lower the amount of CO2 and H2S to the level of export pipeline specifications. Although the plan does not specify what percentage of those gases will be in the export stream, it states, “The CO2 retained within the Jackdaw gas for export is expected to make up approximately 44% of the total CO2 content of the produced gas.”

From there, the gases removed will either be transported by pipelines to shore or vented out of an “alternative atmospheric discharge point.” While the inflammable gases have been included in the stream going to the flare stack in the past, the volumes after Jackdaw would snuff the stack.

The lifetime emissions related to these changes will total 456 kilotons (kt) compared to 800 kt in the original design.