I really enjoyed the first virtual ATCE. Great job by the SPE staff and the ATCE program committee, especially when you put it into the context of having had to make the switch in less than 6 months during a pandemic with people simultaneously learning about how to get things done remotely.

Those who missed ATCE can still register and catch most of the content.

- I love having the ability to revisit the recorded presentations for 90 days in order to update my appallingly illegible notes and/or to catch sessions that I had missed or elected not to attend live. An unexpected and delightful spinoff from the virtual ATCE.

- Those who missed ATCE can still register and catch most of the content.

- Yes, I missed the networking and the receptions; and I agree that the Q&A was a bit clunky, but

- We will get better at that too.

- It is nice to have the option of up-voting good questions.

- My impressions were that most pre-recorded presentations were even better than normal.

- I also liked being in control of the pace in the virtual exhibition booths.

- Look around—read the headlines.

- Catch a video or two and scan/download a few brochures.

- Engage an exhibitor rep or drop off a virtual card.

- Move on. Totally at my own pace. Think I saw and learned more, especially about new players/products.

I am heading back to re-listen to Special Session 10, “Maximizing Subsea Return on Investment: The Future of All-Electric Completions and Subsea Infrastructure.” The session speakers included:

- Alvaro Arrazola, completions engineer, Chevron, N. America Upstream

- Glenn-Roar Halvorsen, project manager subsea all-electric, Equinor

- Christina Johansen, managing director, Norway, TechnipFMC

- Samantha McClean, intelligent wells technical advisor, BP

- Rory Mackenzie, head of subsea electrical technologies, Total R&D

- Thomas Scott, global product line director, intelligent production systems and reservoir information, Baker Hughes

- Moderated by Edward O'Malley, director of strategy & portfolio, oilfield services, Baker Oil Tools

While the session focused on subsea and offshore subsurface applications, it has much wider implications. The discussion included the electrification of both facilities and subsurface systems, as well as more-extensive deployment of sensing and flow control from the surface to the reservoir.

The moderator set-out to explore

- Why electrify facilities and completions?

- Where are we on this journey?

- Why is there increasing interest right now? And why is there not greater interest?

- Where will this initiative be heading after we emerge from the current downturn?

- How can the process be accelerated to meet the business cases?

The stated benefits of electrical controls include

- Greater functionality and real time feedback

- The opportunity to apply a common actuation architecture with increased standardization of components, allowing suppliers and maintenance groups to reduce inventories

- The potential for

- The simplification of the host facilities and umbilicals

- Increased use on not-normally manned or unmanned platforms

- Total subsea developments tied back to shore-based processing and control facilities

- Significant reductions in the total field or area development Capex

- The development of contingent resources currently considered to be marginally attractive under a lower-for-longer product-price scenario

- The opportunity to increase operational efficiency and uptime while reducing the life-of-field Opex

- Interchangeability of components between projects, including the opportunity to re-use refurbished actuators in a sequential development of a series of small, short-life pools (“String-of-pearls” type area appraisal and development plans)

- A reduced-carbon footprint

- Total subsea hub-and-spoke development plans with longer stepouts and/or extending into ultradeepswater (>3000 m or 10,000 ft)

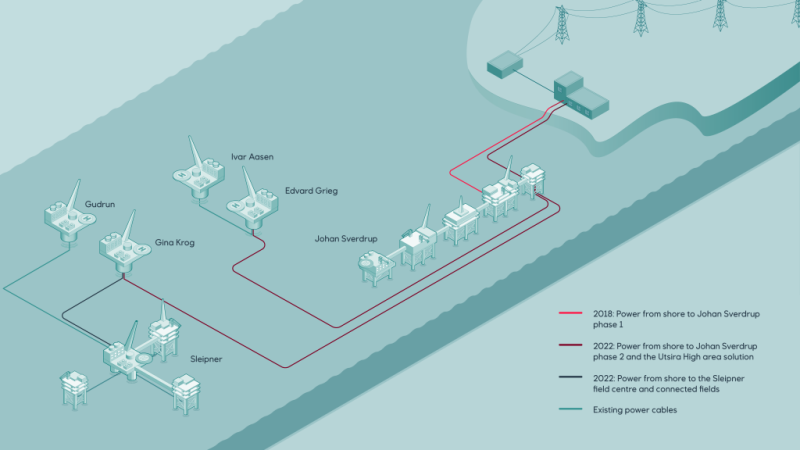

The panelists speculated that with electrical controls, the tieback limits may be controlled by flow-assurance considerations to around 100 km (54 miles) for many oil projects and 600 km (324 miles) for dry-gas developments.

The other key theme in this session was the advantages of electrical control of downhole flow-control devices.

- Many of us have already come up against the limits of hydraulic penetrations of hangers and packers and/or the geometric challenges in getting adequate protection at couplings, across tubing retrievable subsurface safety valves and/or the upper flow-control devices.

- Electrical control offers not only the option of automating wellhead choke control, but also downhole flow-control devices.

- Downhole tools could have greater flexibility and functionality. That includes the deep-set safety or non-return valves if there was adequate, broad-based demand.

- Obviously, the ability to selectively collect early-time downhole data from multiple zones will improve reservoir characterization and modeling.

- With active reservoir management, we should be able to realize a lot more of the promised benefits of digital science and engineering analytics, allowing algorithms to maximize on either value or medium-term cash flow, rather than simply optimizing the operational system.

This transition will require a greater degree of trust in the experience from other industries and in the prediction of ever-increasing reliability of electronics in severe environments.

Why aren’t more of us talking about converting most actuators and active downhole flow-control devices to electrical control? Many projects, facilities, and construction types already know something about a few of the component pieces from our electrical engineering courses at university and/or industry training. However, I understand that this may not extend to some petroleum engineering graduates.

Full disclosure: I graduated as a mining engineer, so the electrification heavy equipment featured heavily on the curriculum. Nevertheless, I found the topic incredibly challenging, especially in thinking about three-phase step-up and step-down transformers, heat losses, and switching between AC and DC transmission. (I made friends with someone who could explain the topic much more effectively for the nonspecialist than the professor, so I got the required grade, but I digress.)

In retrospect, some 20% of my career has been about fuel substitution to increase efficiency, reduce costs, and facilitate remote control and optimization.

- Electrification of artificial lift prime movers and compressors

- Remote control of electrical submersible pumps (ESP) with variable speed drives

- Wellhead and process controllers, SCADA, automation, and machine learning

- Unmanned remote operation of oil batteries, compressor stations, pads/platforms/subsea manifolds and wells

- Economic justification of downhole gauges and semi-smart completions with hydraulic or electro-hydraulic inflow-control devices

- Identifying the optimum location of the power plants in gas-to-wire projects, given that pipelines are so efficient and are often an easier sell than new power line corridors

- Application areas for subsea cables and connectors

When I first arrived in Canada, my team was investigating why a competitor had much lower lifting costs than we had been able to achieve. We realized that they had electrical engineers assigned to their artificial lift optimization teams. As a result, their power supply contracts were better than ours, their power losses were lower, and the mean times to ESP motor and cable failures were significantly longer.

In 2014, I worked on a tight-gas sands conceptual field development program team for which the base case envisioned that a substation would be the first thing that was placed onto the super pads. (I hasten to add that, regrettably, this bright idea did not come from me.)

- This concept had a lot of merit given that

- The project was not far from the grid and a highly efficient, combined-cycle gas-fired power plant, which was a potential gas-marketing target.

- Oil was imported into the region, so diesel costs were relatively high.

- The ESG advisors anticipated that a commitment to reduced emissions would accelerate approvals and planning permission might include onerous nighttime noise restrictions.

- Conceptually, the rigs and frac spread would have been electrified, as well as the compressors and pumps.

- So, why not total electrification of the entire system including all the actuators?

What is inhibiting us from accelerating the import of more stuff from the military, the aerospace and auto industries, and our own mid-downstream sectors?

Obviously the technical and commercial risk assessments are much more challenging than opting for something with which we have 50 years of experience and well-defined remediation measures in the event of a failure.

Apparently, there are several API and ISO subcommittees working on new and revised, fit-for-purpose standards. The major operators and suppliers have access to a decade or two of pilot test data and several electrification JIPs in progress.

So, why is there not much more discussion and excitement within the SPE Production & Facilities Community? Perhaps, we need an oilfield electrification technical section?

It seems to me that there are lots of intellectually satisfying challenges and value creation opportunities in the “electrification of just about everything in the oil and gas exploration and production business.” Moreover, the required skills are highly transferable. If we see ourselves as the suppliers of safe, reliable affordable energy, renewables become a new opportunity rather than a threat.

Bob Pearson, Glynn Resources, is the SPE Technical Director for Production and Facilities.