As of September, TotalEnergies together with partners Eni and QatarEnergy will have spud exploration well 31/1 on Block 9 of Lebanon’s Qana prospect. It is the consortium’s second attempt in 6 years to strike gas in the EastMed where upstream riches at the crossroads of markets east and west struggle against the fiercest of global geopolitical headwinds.

Lebanese media hailed the 16 August arrival of the Transocean Barents semisubmersible drilling platform at Block 9 with guarded optimism, reporting on the Barents journey from the North Sea like a sports play-by-play, detailing the landing of the first crew transport helicopter and the offloading of pipe and other equipment delivered by ship to the Port of Beirut.

The Lebanese Petroleum Administration busily dotted the i’s and crossed the t’s on the drilling license application that TotalEnergies EP Lebanon had submitted in June while MP Ibrahim Kanaan, head of the parliament’s finance and budget committee, announced creation of the Lebanese Sovereign Fund for Oil and Gas to protect future revenues from political interference.

“The rig will start working in Lebanon in September ... before the end of the year we will know if there is a discovery,” Lebanon’s caretaker Energy Minister Walid Fayyad told Reuters at an event earlier this summer in Abu Dhabi.

Built to operate in harsh environments the Barents will drill in deep water, its crew hoping to hit the sweet spot that is the Tamar Sands Formation from which Israel, Cyprus, and Egypt are producing gas or developing fields for domestic needs and for export.

Assuming commercial gas reserves are confirmed in Qana, Lebanon will join the club of EastMed gas producers—a development that would ease Beirut’s seemingly endless energy crisis, give the financially bankrupt country a share of revenues for gas exported to Europe and Asia, and attract further global investment. The World Bank has described Lebanon’s economic collapse as possibly one of the top three most severe worldwide since the 1850s.

But while all seems like business as usual, this is the EastMed where political and military conflicts that dog oil and gas projects throughout the world can escalate quickly, driven by political fragmentation and violence within and across borders of countries with the most to gain from big international projects.

What might be called a harsh environment in the UK sector of the North Sea where the Barents worked most recently differs greatly from what can be called harsh in the EastMed where technology can’t solve all of a hydrocarbon project’s problems.

Drawing Lines in the Sand

Beirut awarded exploration licenses in 2017 to drill on its offshore Blocks 4 and 9 to the Total-lead consortium with Eni and, at the time, Russia’s independent gas producer and LNG exporter Novatek. This past January, QatarEnergy farmed in for a 30% stake after Novatek exited.

TotalEnergies and Eni each now hold 35%.

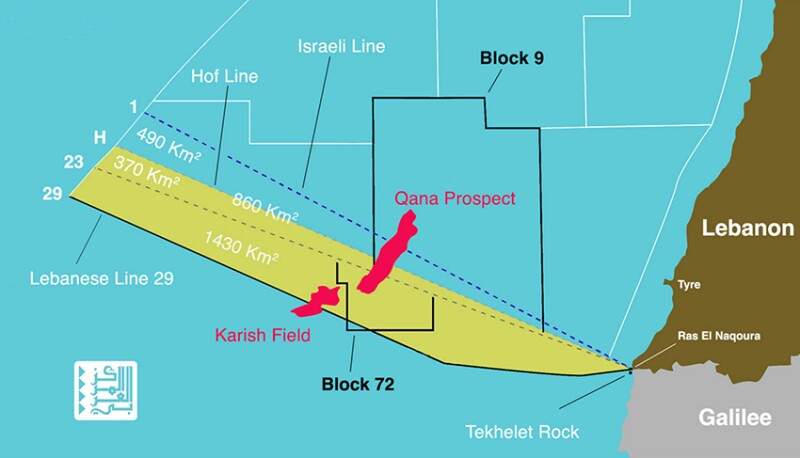

In the 6 years following the license award, the consortium drilled only one well on the Lebanese shelf—a dry hole on Block 4 in 2020. Though data suggested that the Qana prospect in Block 9 might be different, TotalEnergies delayed further appraisal drilling pending settlement of the maritime boundary between Israel and Lebanon.

An agreement was reached in October 2022 when the two nations, at war for decades and having no diplomatic relations with each other, signed a US-brokered deal to split Qana between them. At the same time, TotalEnergies pledged to act as middleman, working exclusively with Lebanon as regards control of Qana but managing financial relations with Israel should commercially viable gas reserves be confirmed.

“As for the general geology, the Qana prospect belongs to the Levantine basin/zone so it should be of similar geological layers to a certain extent (to that of Block 4),” according to Kamel Bou-Hamdan, assistant professor at Beirut Arab University. “Block 4 was drilled through a thick salt layer of around 1 km thickness … using an S-shaped directional profile which can be useful in avoiding some faulty or problematic zones.”

A member of the TWA Editorial Committee, Bou-Hamdan described those problems in an article published in The Way Ahead as bit-balling, wellbore erosion, well-control issues, and salt creep, all problems related to drilling for hydrocarbons (in this case mainly gas) that are trapped in a carbonate formation topped by a thick layer of salt, further complicated by ultradeep water.

He also cited OTC 19880, Pre-Salt Santos Basin—Challenges and New Technologies for the Development of the Pre-Salt Cluster, Santos Basin, Brazil, as relevant to conditions found in the Levantine basin.

Playing Hide and Seek With the Tamar Sands Formation

Having struck out on Block 4 to the north, TotalEnergies and its partners must find commercial quantities of gas on Block 9 to confirm that Lebanon does indeed share in the mother lode that is the Tamar Sands Formation. TotalEnergies awarded Transocean “a one-well contract at a rate of $365,000 (per day) plus three one-well options at rates that may vary between $350,000 and $390,000,” according to Transocean’s quarterly fleet status report.

If the consortium succeeds, Lebanese energy authorities will again extend their bid round for another eight exploration blocks for which there have so far been no takers, Minister Fayyad has said.

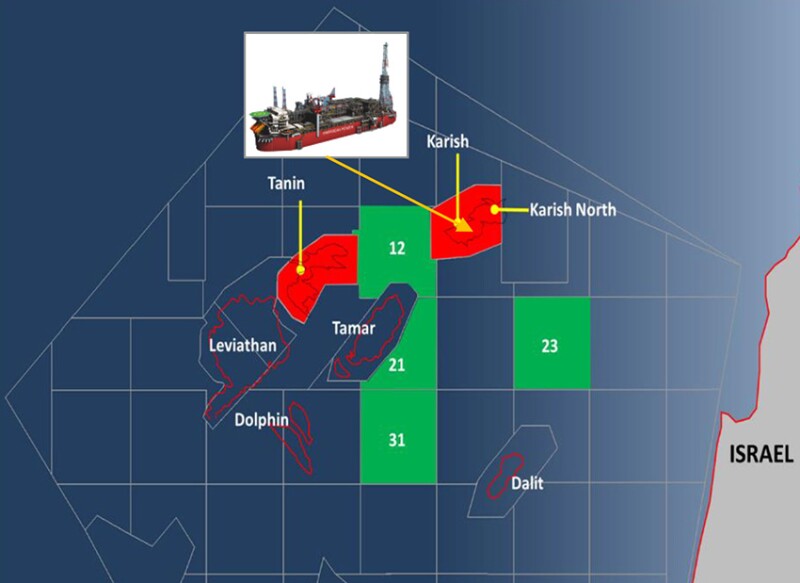

On Israel’s side of the maritime border, Energean, a UK-Israeli-listed E&P independent, is using its own (and the EastMed’s only) floating production, storage, and offloading (FPSO) facility, Energean Power, to produce the Karish field.

Like TotalEnergies did in Lebanon, Energean slow walked its Israeli project, waiting for security reasons to bring production on stream until both nations agreed who would own what. Energean did busy itself, however, with the prep work so that first gas flowed from Karish on 26 October 2022, only 4 days after the border deal was announced.

Energean completed installation of a gas export riser in March to enable the FPSO to reach its 8 Bcm/year nameplate capacity. By year-end 2023, the company expects to complete its second oil train to boost liquids production to around 32,000 BOPD.

Meanwhile, a network of deepwater tiebacks is being fashioned to link the Energean Power to other fields within a 55-km radius including Karish North, the Tanin field, and the Olympus Area in Block 12 which has been renamed Katlan (the Hebrew word for orca, colloquially known as a killer whale).

The company is now finalizing a development plan to submit to Israeli authorities, detailing how it will exploit Katlan’s 68 Bcm of estimated gas reserves. In March, Energean also reported first gas from its offshore North El Amriya and North Idku project in Egypt.

Israel kicked off deepwater pre-salt exploration in 2003 on its own shelf by drilling the Hannah-1 dry hole, according to an abstract from the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) book, Giant Fields of the Decade 2000–2010.

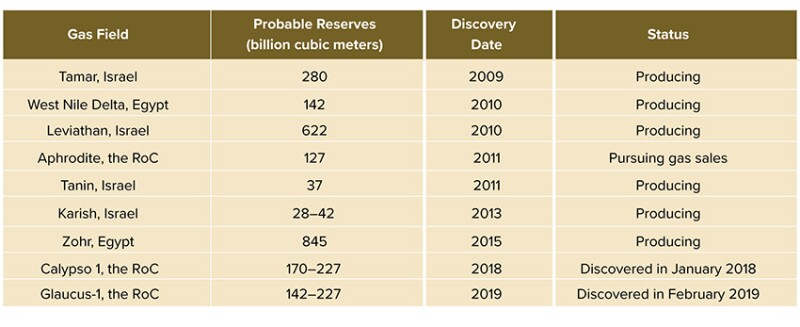

Five years later, Israel rebooted its campaign, “resulting in gas discoveries at Tamar, Dalit, Leviathan, Dolphin, Tanin, Aphrodite, Karish, and Tamar Southwest. The main pre-salt play area likely extends nearly 30,000 km2 (11,583 sq mi) in water depths of approximately 1300 to 1700 m (4,265 to 5,577 ft) in the exclusive economic zones of Egypt, Israel, Cyprus, Lebanon, and Syria,” according to the AAPG publication.

But so far, only Egypt, Israel, and Cyprus are successfully developing any of their EastMed prospects into producing assets, some ranked among the world’s largest deepwater discoveries.

Writing 2 months after Lebanon delimited its border with Israel, Middle East Eye (MEE), an independently funded London-based news site, noted that even rougher waters might lie ahead with Syria at the center of a possibly developing storm.

With Israel and Lebanon having etched their lines in the sand with US help, Cyprus can now settle its border with Beirut without upsetting Israel.

However, Syria ultimately has a say because “the maritime zones of Lebanon, Syria, and Cyprus are linked by one point,” MEE pointed out in an analysis of the 2022 delimitation. While this doesn’t affect development of Qana, it could stymie Lebanon’s ability to attract investment in the eight other blocks it wants to license.

It is there that Qatar and QatarEnergy as a partner with TotalEnergies and Eni in Lebanon might intervene in the deal making.

Navigating the EastMed’s Troubled Waters

Arab investment in EastMed Israeli waters became possible only in August 2020 with the signing of the aptly named Abraham Accords which normalized diplomatic relations between Israel, the UAE, Bahrain, and Morocco. Sudan followed suit in February of this year.

Because Qatar declined to sign the Abraham Accords, Doha has the flexibility to play a special role in sensitive negotiations with countries that remain in open conflict with Israel—most importantly Lebanon and Syria.

Qatar has room to maneuver also with Turkey, another willing mediator with ambitions to become a gas hub for the EastMed considering that Ankara is a gateway into southern Europe for pipeline gas from the Caspian and Black seas.

A skeptic on this matter, Carole Nakhle, CEO at London-based Crystol Energy, wrote in an email, “Egypt stands a better chance than Turkey to become a gas hub. That has been Turkey’s ambition for decades, but its role has been limited to a transit route apart from its large domestic market.”

Qatar had broken diplomatic ties with Israel in 2009 over the conflict in Gaza, but the Washington-DC based Middle East Institute notes that the Qatari government has maintained a practical “under-the-radar working relationship” with Israel, as does Oman.

Qatar is in fact the only country currently investing in Lebanon and is even trying to help its defunct banking sector. QatarEnergy’s farm-in to the Qana consortium when no other international energy company offered to acquire Novatek’s abandoned share is but one example.

Abraham Accords in Israeli Waters

As for the Abraham Accords, the peace agreement bore its first fruits in April 2021 when Abu Dhabi’s state-owned Mubadala Petroleum (now Mubadala Energy) announced its intent to purchase Delek Drilling’s stake in Israel’s Tamar gas field for $1.1 billion.

Mubadala currently holds 11% in Tamar with operator Chevron Mediterranean Ltd. controlling 25%. Israeli partners include Isramco (28.75%), Tamar Petroleum (16.75%), Tamar Investment 2 (11%), Dor Gas (4%), and Everest (3.5%).

In December 2022, the Abu Dhabi company joined Chevron and its other partners in taking a final investment decision (FID) of $673 million to lay a third pipeline to the Tamar production platform to boost production incrementally while also negotiating new sales agreements with Egypt.

Chevron is making similar moves at the Leviathan gas field which it also operates, and its biggest Israeli partner, NewMed Energy, with a majority 45.34% stake, may in the not‑too-distant future be inviting the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC) and BP into an expanded partnership.

In March, ADNOC and BP agreed to explore a possible purchase of 50% of shares in NewMed, a subsidiary of Delek Group, and to take the company private

If this happens, Abu Dhabi will be well positioned in the EastMed with stakes in Israel’s two most-prolific gas reservoirs which currently supply regional needs and are executing plans to expand production for LNG export.

Leviathan is the Mediterranean’s largest natural gas reservoir with an estimated 622 Bcm in reserves. Israeli’s Ratio Energies is also a partner with a 15% stake with Chevron Mediterranean Ltd. holding 39.66%.

The announcement of NewMed’s possible tie up with ADNOC and BP came only a month after the Israeli company and Chevron unveiled a $45-million plan to expand Leviathan’s production and to invest $51.5 million in developing a 6.5 Bcm/year capacity floating liquefaction facility (FLNG) that would operate in Israeli waters.

Leviathan supplies the 12 Bcm/year of gas it currently produces to Israel, Egypt, and Jordan. The project’s Phase 1A was designed to eventually raise gas output 43% to 21 Bcm/year by adding modules to existing facilities, according to NewMed.

Chevron and NewMed took a first step in this direction when they announced in July a FID to invest $568 million to lay a third pipeline on the Leviathan field to gather an additional 2 Bcm/year of gas starting in late 2025.

Phase B envisions the export of LNG to Europe and to Asia via the Suez Canal, with liquefaction taking place at one or both of Egypt’s two existing LNG facilities or by developing NewMed’s own FLNG capability.

The Jerusalem Post observed in a 12 July article that “commercial and technical bottlenecks” encountered once Israeli gas arrives in Egypt, plus the limited capacity of Cairo’s two liquefaction plants, argue for Israel to diversify its gas export options by anchoring an FLNG facility in the country's offshore exclusive economic zone.

Meanwhile, Chevron and NewMed may need to add such multivector thinking to deliberations over the development plan for the Aphrodite field on Block 12 offshore Cyprus, which Cypriot authorities rejected in a 25 August letter to Chevron Cyprus Ltd. The government’s letter noted that the development plan to bring Aphrodite gas on stream speaks only of constructing a subsea pipeline and connections to existing infrastructure in Egypt, minus any mention of other options such as installation of an FLNG facility near Aphrodite.

China Petroleum Pipeline Engineering Co. has again delayed delivery of a floating storage and regasification unit (FSRU) to be sited at an LNG import terminal at the Cypriot Port of Vassilikos and nearby power station. Originally due to be delivered by October, the Chinese contractor now promises to complete the project by July 2024, the Cyprus Mail reported this summer. Besides delivery of the FSRU, the EUR 300-million project includes a jetty, pipeline and mooring facilities, and related offshore and onshore infrastructure.

An EU grant will finance a third of the cost with remaining finance coming from the European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

For Further Reading

OTC 19880 Pre-Salt Santos Basin—Challenges and New Technologies for the Development of the Pre-Salt Cluster, Santos Basin, Brazil by Ricardo L. Carneiro Beltrao, Cristiano Leite Sombra, and Antonio Carlos V.M. Lage, et al., Petrobras.

The Tamar Giant Gas Field: Opening the Sub-Salt Miocene Gas Play in the Levant Basin by Daniel L. Needham, Henry S. Pettingill, and Christopher J. Christensen, Noble Energy Inc., et al. The American Association of Petroleum Geologists.

IPTC 21893 The Ionian-Crete Basin: Is This the Next Frontier? by Farisa M. Zaffa, Amir Ayub, and Shahram Sherkati, et al., Petronas.

Isolated Carbonate Platforms of the Mediterranean and Their Seismic Expression—Searching for a Paradigm by Giovanni Rusciadelli and Peter Shiner, University of Chieti-Pescara, The Leading Edge, SEG.