What is unconventional exploration and production in Spanish? YPF goes with “no convencional.”

The translation, not conventional, is a literal description for the sort of ultratight reservoir rock in the Vaca Muerta, the huge formation that the Argentine oil company says can return the country to the ranks of energy-exporting nations.

Not conventional is also the essential mindset required to do something nobody else in the world has accomplished: develop a massive shale play outside the US and Canada.

The potential is there. The US Energy Information Administration ranks Argentina second in the world among unconventional formations for technically recoverable gas and fourth for oil.

When YPF announced the discovery of a world-class shale play in 2011, it marked the start of years of work to solve a multidimensional puzzle presenting daunting geological, business, and political problems that has stymied the global spread of unconventional development. In the 6 years since then, YPF has shown it is possible to make money drilling and completing wells when oil prices are around $50/bbl while developing a block with Chevron.

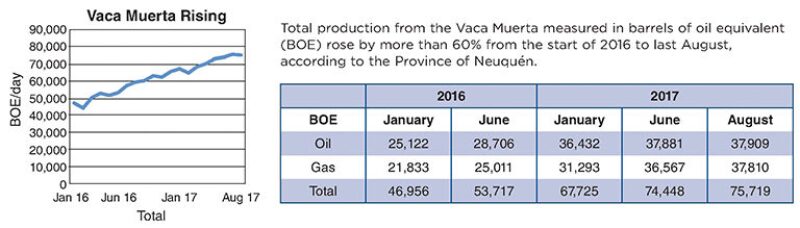

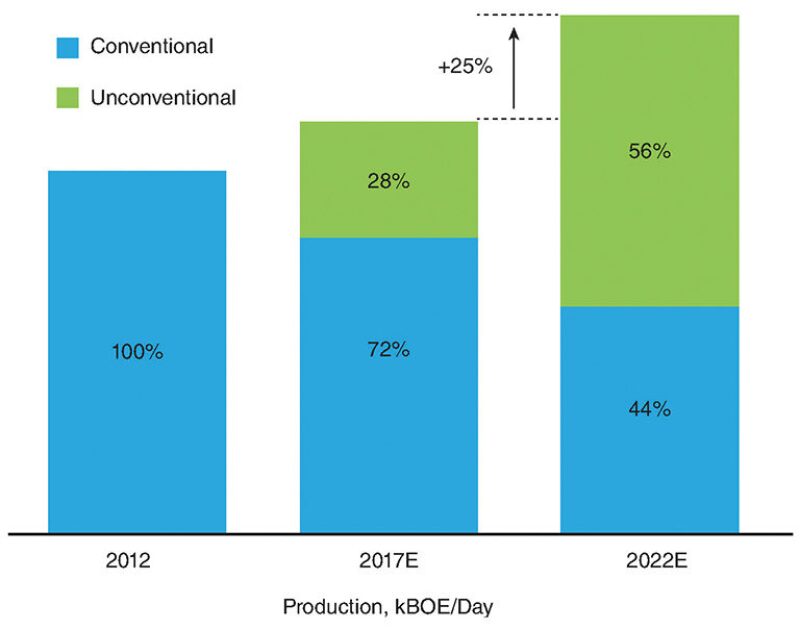

During a 3-day visit to Argentina, YPF offered a close look at what it is doing to deliver on its prediction that unconventional oil and gas will account for more than half the oil and gas produced in Argentina by 2022. The company’s share of unconventional production totaled 37,200 BOE in the third quarter of 2017. This includes output from Vaca Muerta plus gas flowing from tight formations that require simulation but are not as tight as shale.

“We put it all together from nothing in 6 years,” said Pablo Bizzotto, vice president for upstream at YPF. “The new stage is to gain scale.”

Undertaking this unconventional challenge required a willful disregard for the many good reasons why this development was not possible.

In the beginning, there was a team of eight professionals assigned to the project who had little money to spend, in a country lacking the basic tools used for unconventional development—horizontal drilling and fracturing equipment and crews—and where government policies discouraged investment from international companies whose money and know-how would be required.

But they have built a foundation for the future that has drawn a growing group of international oil and service companies investing in the potential of the Vaca Muerta.

After looking around the world for a spot for its first international arm, Joseph Sites, president and chief executive officer of Allied-Horizontal Wireline Service, picked Argentina because it combined rich resources and people with a desire to develop the technology needed to tap it.

“It looks like Vaca Muerta is here to stay,” said Sites, who spent years setting up the business in what he describes as a complicated business environment. “It is not a gamble. But it is not a guarantee either,” he said.

Missing Pieces

The project began by collecting every bit of data held by YPF, which had often drilled through the Vaca Muerta on the way to conventional fields that once made Argentina a rich energy exporter. Vertical wells were drilled to collect well logs and rock samples to add detail.

An early focus was the area near Añelo, a remote desert town with little past production.

“In May 2011 I was here to do an open-hole log. There was nothing around,” said Matias Fernandez-Badessich, senior advisor, reservoir engineering for YPF, who was involved from the start. “There was a well and the rig and nothing. Absolutely nothing.”

With every later visit there was more activity as YPF created a more detailed picture of the complex formation subject to abrupt change. “Imagine a puzzle where you have just a few pieces of the puzzle. The rest you have to imagine, you had to be really creative,” said Guillermina Sagasti, the geologist who is leader of subsurface exploration studies for YPF, when describing what it was like to build a map of the play.

“The Vaca Muerta was like the Eagle Ford in some parts. The high pressure is also like the Haynesville, and then the Vaca Muerta is very thick like the Wolfcamp” in the Permian Basin, Sagasti said. With productive rock ranging 100–300 m thick they hoped vertical drilling could also be used to develop the formation, but like operators in the Wolfcamp they realized horizontal wells were many times more productive.

Unlike their counterparts in the US, the drilling equipment and skilled crews they needed were not readily available. “We did not have experience with horizontal wells in Argentina,” Bizzotto said.

When YPF drilled its first horizontal Vaca Muerta well in 2012 there was so little equipment available, “we paid what they asked,” Fernandez-Badessich said.

Horizontal drilling was more productive, but not enough to justify the cost. YPF addressed that problem by jump-starting the horizontal drilling business by leasing 10 modern, 1,500-horsepower FlexRigs from Helmerich & Payne in late 2014.

To get around the high cost of imported sand, it developed mines in Argentina able to produce the fine-grained particles needed to prop fractures, and built a plant nearby Añelo to clean and sort it into the sizes needed for fracturing.

Lacking the expertise for this unconventional challenge, it created a startup company within the national oil company staffed mostly with young, local professionals that totals more than 550 and growing.

Critical Partners

In 2015 the project took a big step forward when YPF signed deals with three partners—Chevron, Dow Chemical, and Petronas. And took a big step back as it became clear that oil prices at $50/bbl or less were a lasting reality, meaning they had to find a way to produce oil for half the cost they expected to justify development.

Progress since has been measured by what YPF and Chevron have done within the 300-km2 area of the Loma Campana block near Añelo.

- The drilling cost per foot dropped from $2.73/ft in late 2015 to $1.62/ft in the third quarter of 2017.

- The cost per barrel to develop wells dropped from $25.30 in 2015 to $13.40 in 2017, and is expected to soon hit $10.

- Proppant costs were halved when YPF started a sand-processing operation. It expects to pare that cost by 20% or more by producing sand closer to the play.

When horizontal drilling became the norm in the Loma Campana, the number of rigs working dropped to five in late 2016, less than a quarter of the peak number of vertical rigs working before the switch. But the output of those wells was so much better that production continued rising.

That year Argentina elected a new president, Mauricio Macri, who promised to change government policies hindering unconventional development. Since then he has acted to “provide that stable investment climate allowing operators to get capital in and out, to import specialized equipment at a reasonable cost,” and alter costly labor contracts, said Robert Lewis, senior research analyst for Latin America upstream for IHS Markit.

The combination of falling production costs and a more attractive political climate last year allowed YPF to attract $4.2 billion in exploration commitments from eight oil companies.

The exploration map for the Vaca Muerta expanded with new projects involving current partners such as Shell, ExxonMobil, and BP’s PanAmerican Energy, plus new ones such as Statoil and Schlumberger. While YPF is at the center of development, majors such as Shell and ExxonMobil also have blocks they operate on their own.

The current rig count of around 18 working for YPF and others would rank the Vaca Muerta below six US shale plays, but the potential growth if these exploration programs become development programs has drawn the big names in the service business.

“The rock is there. The improvements made during the last 3 years have been impressive in well construction and well completions reducing the cost per well, and ultimately the cost per BOE,” said Jorge Rivera, senior country manager, Argentina, for Halliburton.

But more needs to be done. “We see the industry facing other challenges related to logistics, infrastructure, and regulations, which may prove to be a challenge when activity scales up,” he said.

YPF needs to show that the development and production costs achieved in the initial development blocks can be replicated in places that do not have access to the underused pipeline and processing capacity found in Loma Campana. It needs to compress the time required to adjust to the subsurface surprises as it transfers what it has learned over the 30,000-km2 play. Doing so will require dealing with known problems, from gaps in pipelines and processing to costly services and supplies, and unknown ones such as labor problems that can flare up and unexpected subsurface obstacles.

Above the ground, YPF’s growth targets are both ambitious and daunting. It predicts a 150% increase in unconventional production by 2022 from Vaca Muerta and tight gas formations. And that will be accomplished with a capital expenditure budget for exploration and production averaging $3.4 billion a year, 13% less than the average over the previous 5 years. A company that traditionally did not seek out partners for domestic developments absolutely requires them because that budget is far less than what IHS Markit expects will be needed to reach peak production.

While there were a growing number of big companies added to the Vaca Muerta block map, the number of drilling rigs working there is still low compared with the scale of YPF’s plans.

“They still need to drill a lot of wells to delineate the sweet spots for the play to take off,” Lewis said.

Also part of this series...