It is easy to fixate on what it will take to extract huge volumes of oil and gas from the nearly impermeable rock within the Vaca Muerta.

But in terms of the future of the huge Argentine unconventional formation, “the aboveground risk is far more important in the pace of development,” said Robert Lewis, a senior research analyst covering Latin America upstream for IHS Markit.

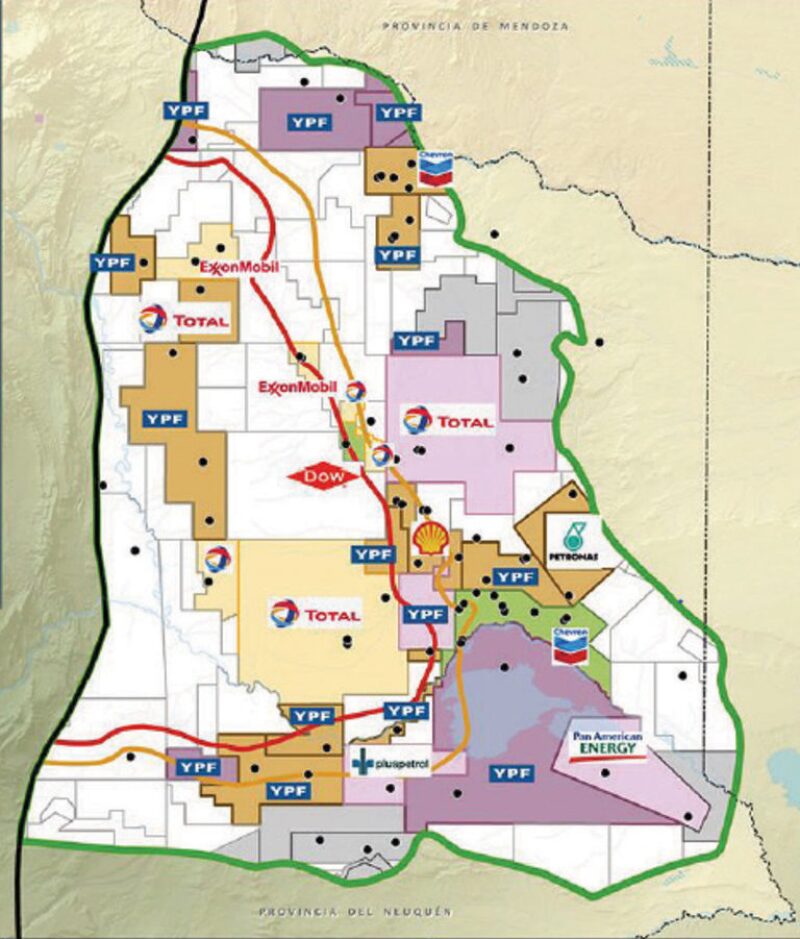

Scaling up this unconventional play will require spending billions of dollars a year and support from government policies that promote a stable investment climate, the ability to move money and goods in and out of the country, affordable deals with labor unions, and improved infrastructure.

For now, government policies are aligned with development. Since he was elected president in 2016, Mauricio Macri has delivered on a promise to push domestic energy growth with market-based policies reducing regulation and labor costs and encouraging international investment. Much needed infrastructure improvements have been promised, particularly efficient rail service from the coast to the oil play in the western side of the country near the border with Chile.

Macri’s economic program got a vote of confidence this fall when his party gained seats in congressional elections, solidifying his position through the end of this decade.

For YPF to reach its goal to increase unconventional production 150% by 2022 it needs continued “favorable investment conditions,” said Pablo Bizzotto, exploration head for YPF, adding “the new government is working hard on this.”

Commitment Required

For the past 2 years, Joseph Sites, the president and chief executive officer for Allied-Horizontal Wireline Services, has been living with the complications of getting into the oil services business. In that time, the US wireline company has managed to bring in two wireline trucks, get all the permits and supplies needed, and hire and train Argentine workers.

“It’s more complicated than just opening a base in the Haynesville,” Sites said, adding, “It takes a real commitment and there is a lot of uncertainty.”

Based on history, government support of oil development by big oil companies in Argentina is not a given. A short item about YPF in Wikipedia lists a dizzying series of changes in company and government energy policies over the past century.

YPF’s unconventional program was born in 2011 at a time when oil and gas production in Argentina was in decline. The problem was that government policies in place then did not support the international investment needed to develop the remaining conventional oil and gas resources, which come with challenges from low-quality reservoir rock on shore to deepwater plays offshore.

“Historically, Argentina’s energy sector policies prompted an imbalance of energy supply and demand by limiting the industry’s attractiveness to private investors, restraining the profits of domestic producers, and shielding consumers from rising prices,” said the US Energy Information Administration in its survey of international shale plays.

Things have changed since then. In 2014, the government of Argentina renationalized YPF, which had been owned by Repsol. The Spanish oil company focused on finding and developing resources in more familiar plays for international oil companies, such as the Gulf of Mexico, rather than pioneering new frontiers like the Vaca Muerta.

The government retained a 51% interest in YPF, with the balance publicly traded, and it refocused its exploration and production effort on Argentina. The government badly needed lower-cost domestic production to replace the liquefied natural gas imports it has used to meet growing demand from consumers paying a price that does not cover the cost of imports.

To encourage gas exploration, the government offered the country’s oil producers $7.50/Mcf for gas from unconventional and tight formations. As a result production rose a bit in 2014—after years of declines dating back to 2008—and the growth rate has risen since. In addition to working on the Vaca Muerta, Argentine producers have been adding production from tight gas formations, which do not require as much effort as developing ultratight rock.

While the business climate for energy companies has improved, there is work to be done. “The country lacks a reliable railroad network” needed to expedite imports of equipment and supplies, said Jorge Rivera, senior country manager, Argentina, for Halliburton.

Still the falling price of production per barrel sets the stage for growth in the Vaca Muerta. Sites sees little change in the drilling rigs working in 2018 while new blocks are being explored, but said the number could double in 2019.

The process will stretch past 2020 when a new president could be in charge and global energy markets could look totally different. The mood now is upbeat as exploration spreads, but those involved recognize that the future is hardly certain.

There are so many groups that must cooperate for a play like the Vaca Muerta to work—oil companies, government leaders, unions, service companies, investors, and the people of Argentina. “A lot of people have to hold hands and get together and make it happen,” Sites said.