Last time the oil industry faced a significant downturn in 2014–2016, companies were forced to cut costs and streamline operations. Since then, most of the industry kept those lean practices to reflect positive balance sheets.

This time the industry is facing a different set of circumstances; those same cost cutting measures in place over the past 4–6 years have made it difficult for companies to implement any further reductions.

Wood Mackenzie and Rystad Energy outlined some of the key differences between the last downturn and what’s currently playing out, as well as outlining which sectors will likely be targeted for reductions.

What’s Different This Time?

Supply/demand fundamentals led oil prices down between 2014 and2016, especially in the US. This year, a drop in global demand brought down Brent and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude prices.

“We have some idea of what we’re going to expect in terms of cuts to operating costs and capex, and in terms of dividends being suspended,” Ed Crooks, Wood Mackenzie vice chair, said. “In some cases, companies are doing everything they can to conserve cash. But clearly this is a different kind of shock.”

Crooks also pointed out how fast oil prices came down this year compared to 2014–2016.

Nymex WTI futures went from just over $100/bbl to below $30/bbl in about 18 months between 2014–2016. This year, WTI futures went from a yearly high of $63.27/bbl on 6 January to an 18-year low of $20.09/bbl on 30 March—in just under 3 months.

“If you draw back to last time there was an oil price crash between 2014–2016, investment fell 40% but production still grew throughout that entire period,” Rob Morris, Wood Mackenzie principal analyst for Caspian and Europe upstream oil and gas, said. “Huge efficiencies facilitated those cuts. This time because of the whole exercise of cost cutting, we think there’s not a whole lot more fat to cut. That means oil price pressures will result in very deep cuts again, but this time activity is likely to fall. That’s how things are slightly different this time around.”

Offshore drilling has reduced the time it takes to drill a well from 104 days in 2014 to only 70 days now. Within shale drilling, efficiency has climbed from 17.5 wells per rig per year to 22 in 2017.

No matter how fast prices have fallen or how weak demand is, oil companies must decide which areas to cut.

No Sectors Are Safe

Morris said no areas will escape, and while there is a wide range of uncertainty, companies are quicker to react this time around. The areas that are easiest to cut are short-cycle investment in the lower-48 US states, and pre-final investment decision (FID) projects. The easiest way to cut capex spending, according to Wood Mackenzie’s experts, is to not spend and defer.

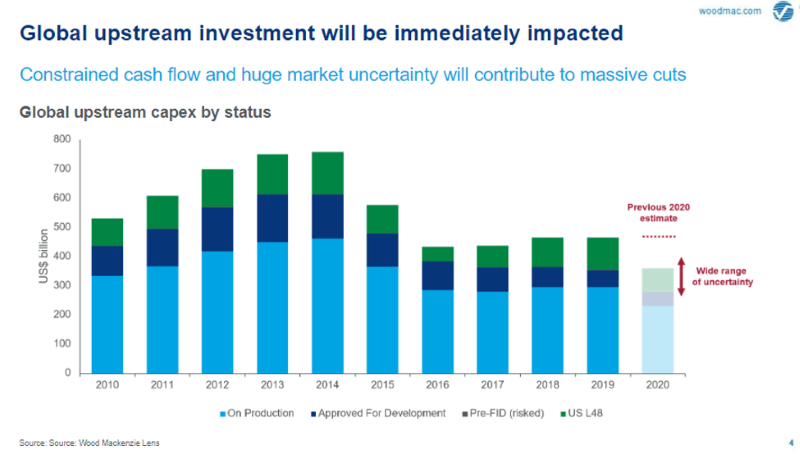

Wood Mackenzie lowered its 2020 global capex estimate from under $500 billion to just under $400 billion, but noted with the wide range of uncertainty, risk remains on the downside.

“Almost on day one companies were announcing revised budgets,” Morris said. “Most of the majors have announced cuts in the range of about 20% vs. their previously announced full-year budgets.”

Morris added this could be the first round of budget revisions, as some companies have lowered their expenditure plan twice during this crisis to preserve liquidity.

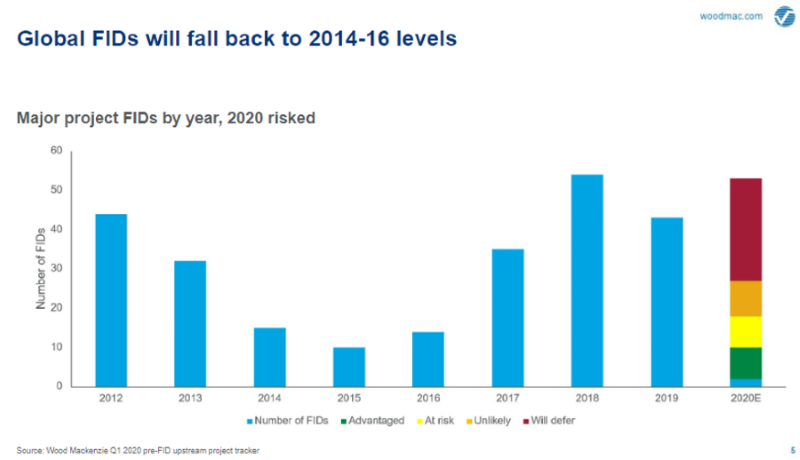

Wood Mackenzie tracks all project FIDs globally. The graph shows projects greater than 50 million B/D. The company expects 2020 to have a similar drop in FID compared to 2014–2016, as many oil majors have announced reviews and deferrals of high-profile projects.

Most projects look robust at $50/bbl, but almost none of them work at $30/bbl for break-even costs. So only the most strategic and the most core projects are likely to get the go-ahead, Morris said.

Wood Mackenzie expects the lower-48 to see the most immediate and dramatic cuts to investments given the short-cycle nature of shale development vs. most large-scale, long-cycle conventional projects in which capital plans tend to be far more “sticky.”

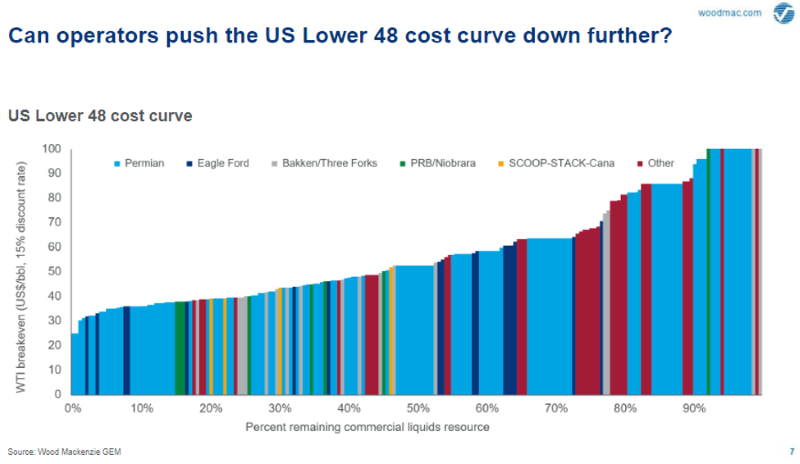

Another challenge, according to Wood Mackenzie’s Linda Htein, is reducing cost curves. Htein, a senior research manager, agrees that since the last downturn, operators were able to substantially bring down the cost of development and continue to grow production over the subsequent 3 years, taking advantage of reduced service cost, optimized well design, and improved operational efficiencies.

“Unfortunately, they were so successful in doing these things that today it’s just much more challenging to push that cost curve down further,” Htein said.

The chart below shows lower-48 cost curve with WTI at a breakeven at a 15% discount rate for all remaining commercial resource in the lower-48, colored by play. At WTI $35/bbl, Htein said 10% of that resource will deliver a return.

For companies within Wood Mackenzie’s coverage, assuming Brent prices stay at $35/bbl for the year, she said companies need to cut discretionary spending by 40% year-on-year just to stay cash-flow neutral. With the second quarter underway, companies must make deep cuts quickly.

“A least a dozen lower-48-focused operators we have heard from, on average have revised capex budgets down by 30% from original guidance,” Htein said.

Some major operators such as EOG, Pioneer, and Apache are among those that have also made revisions for 2020.

As oil majors work to reduce budgets and costs, E&P operators are also looking to trim fat where they can.

What About Supply Chain Cost?

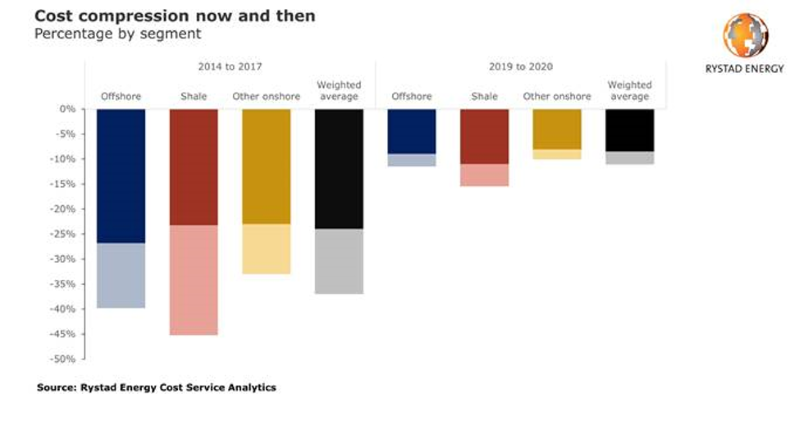

Research group Rystad Energy agrees the current crisis will make efficiency and productivity improvements difficult because much of the potential has been exhausted since the 2014 oil-price drop and not many inefficiencies have arisen since then

As a result, global E&P operators will only be able to cut supply chain costs by up to 12% this year, according to Rystad. About 9% of the cuts relate to service prices and 3% to efficiency improvements. The company said it expects similar cuts within shale (-16%), offshore (-12%), and other onshore (-10%).

“Operators cannot rely on the supply chain to help them make uneconomic production and projects economic again in the very depressed oil market,” said Audun Martinsen, Rystad Energy’s head of energy service research. “This time around, the global oversupply and the demand destruction from Covid-19 will have to be resolved to get project economics back on track.”

A 12% reduction is well below the total 37% reduction Rystad outlined in cost comparison during the downturn in 2014–2016. Within shale, the cost compression was as much as 45%, and 40% for offshore.

Rystad added that although fracking margins are still at 10% and overall margins for the top 50 companies have rebounded to 15%, they do not expect to see much price deflation in 2020. In the offshore drilling segment, the company believes there is room for prices to come down as certain asset classes have seen rig rates improve 30%.

However, Rystad noted the supply/demand balance is significantly different than before the last downturn, making it harder to expect lower rates.