With natural gas destined to replace coal as its fuel of choice, Southeast Asia is unabashedly expanding its oil and gas industry to meet the skyrocketing energy demands of a booming population and unprecedented economic growth.

Investments in regional hydrocarbon projects through 2029—particularly those in natural gas production—are forecast to exceed 4% compound annual growth rates with the spotlight on the region’s top two petroleum producers, Indonesia and Malaysia, according to the London-based Energy Council, a global network of senior energy finance executives.

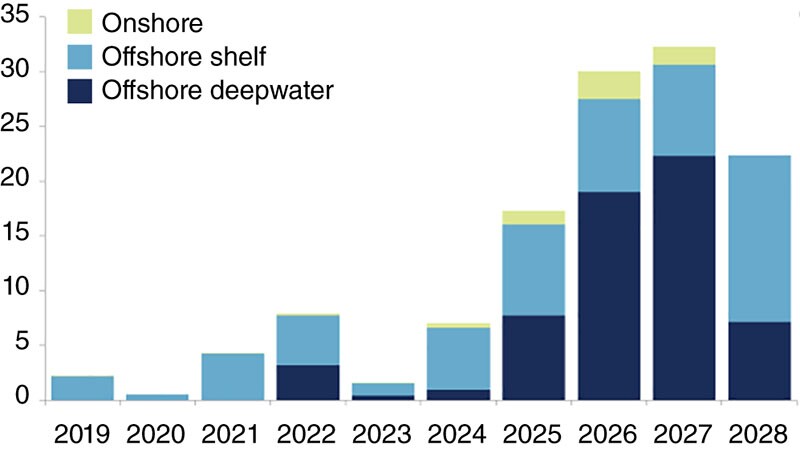

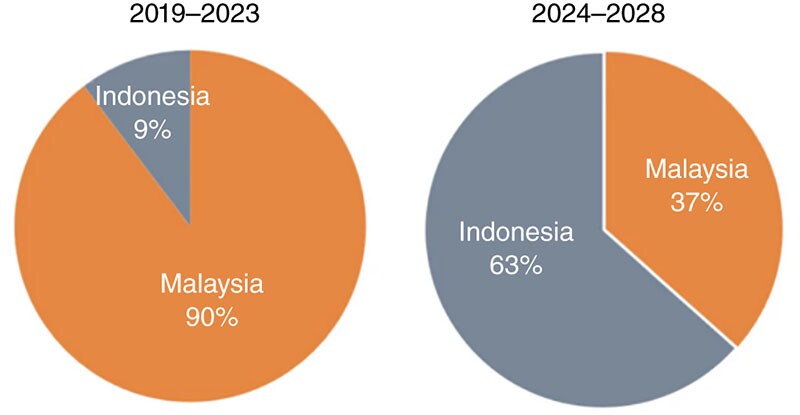

Norway’s Rystad Energy predicts that final investment decisions (FIDs) will be made between now and 2028 on $100 billion in new projects in the region, twice the $45 billion in FIDs taken from 2014 to 2023.

These will include deepwater projects to develop new discoveries in Indonesia and Malaysia, and projects to create a global hub for carbon capture and storage (CCS) such as the one under study by Malaysian state-owned Petronas and Abu Dhabi’s ADNOC.

The Malay Archipelago (also called the East Indies) is the world’s largest island group, and depending on the methodology of the geographer, it encompasses the 17,508 islands of Indonesia—literally the world’s largest country comprised of islands—and the approximately 7,000 islands of the Philippines.

Indonesia and the Philippines in turn are among the 11 countries that constitute Southeast Asia after adding in Brunei, Burma (Myanmar), Cambodia, Timor-Leste, Laos, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam—all with widely diverse histories, cultures, and religions.

But all with one thing in common: a colonial past forged by adventurers from across Europe who in the 19th century arrived on their shores to extract natural resources to feed the Industrial Revolution at home.

In the case of the earliest industrial oil production in Dutch Indonesia and British Malaysia, those adventurers, over multiple generations, added Southeast Asia to the US and Azerbaijan as cornerstones of the modern oil industry while also breaking John D. Rockefeller’s monopoly of the Asian oil trade by building the first tanker to traverse the Suez Canal.

Shortly after the turn of the 20th century two of these industrialists, one Dutch and one British, merged their companies to create what is today’s energy supermajor known as Shell.

First Oil Launches Dutch East Indies Production Boom

The history of oil production in Indonesia and Malaysia dates back over centuries with tales of a cottage industry of hand-dug wells to comb petroleum seeps for medicine, to waterproof boats, and to light torches and lamps.

As the Industrial Revolution dawned, the Russian czar financed the world’s first mechanically drilled oil well in 1846 in Baku using cable-tool percussion drilling to carve out a 21-m-deep (69-ft) exploration well.

Meanwhile in Asia, a 20-year-old tobacco farmer, Aeilko Jans Zijklert, raised money to drill a dry hole in 1884 on the east coast of Indonesia’s second-largest island, Sumatra, after having analyzed oil traces found on the island that contained 62% paraffin (kerosene).

A year later, he drilled again and struck oil at the Telaga Said concession near the village of Pangkalan Brandan in North Sumatra. Zijklert’s well, Telaga Tunggal No. 1, was for Asia what Baku was for Russia and Titusville was for the US.

A new global industry was taking shape.

As Shell chronicles today on its website: “By 1890, Aeilko Jans Zijlker felt confident enough to convert his ‘Provisional Sumatra Petroleum Company’ into something more substantial, and on 16 June the company charter of the ‘Royal Dutch Company for the Working of Petroleum Wells in the Dutch Indies’ was executed in The Hague.”

After Zijklert’s death in 1890, Jean Baptiste August Kessler took the reins at Royal Dutch. He established a company base at Pangkalan Brandan and by 1898 opened Indonesia’s first oil shipping port at nearby Pangkalan Susu.

Kessler’s greatest contribution, in hindsight though, was to initiate early joint-venture talks with British magnate Marcus Samuel Jr. who owned Shell Transport and Trading Company Ltd.

Shell Transport and Trading Ships First Oil to Asia via the Suez Canal

In 1897 Shell Transport and Trading discovered oil in the eastern part of Asia’s largest island of Borneo in East Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo today), and in 1899 Samuel set up a small refinery at Balikpapan.

In all, as the 20th century dawned, 18 companies were exploring for, and producing oil, in Indonesia and setting up refineries across the islands of Sumatra, Java, and Borneo (East Kalimantan), according to historical accounts.

Note: Borneo is divided politically between Malaysia (the states of Sabah and Sarawak) and Brunei in the north; and Indonesia (Kalimantan) in the south, reflecting the colonial legacy left by Britain and the Netherlands. Java (Dutch Indonesia) is found southeast of Sumatra and south of Borneo.

While Royal Dutch dominated production and refining in the region, Shell Transport and Trading controlled oil transport and marketing in Asia through its network of business contacts passed down by Samuel’s father who had traded in ornamental seashells coveted by the Victorians—hence the company name Shell.

In 1902 Shell and Royal Dutch, while remaining separate entities, created a joint company to handle shipping and marketing on behalf of both firms, The Shell Transport and Royal Dutch Petroleum Co. Ltd.

When after a few years it became apparent that Royal Dutch had the edge in oil production and refining, Samuel proposed a merger.

Henri Deterding, at the helm at Royal Dutch Petroleum after Kessler’s death, negotiated a 60% controlling stake for Royal Dutch with Shell Transport and Trading owning the remaining 40%. On 24 February 1907, Royal Dutch Shell was born.

Shell Shatters John D. Rockefeller’s Asian Monopoly

Samuel’s first oil trades involved purchasing US kerosene to resell in Japan from Standard Oil Co. and the Asian trading house Jardine Matheson. But when he expanded into selling Russian crude from Baku for the Rothschilds, John D. Rockefeller was not amused.

At the time, Rockefeller’s Standard Oil monopolized the Asian oil trade because it was cheaper to ship US paraffin to Asia. The Rothschilds and Nobel Brothers in Baku wanted a piece of this trade and the Rothschilds in particular were determined to challenge Rockefeller.

The solution lay in cutting costs by shipping Russian crude from the Black Sea port of Batumi (in today’s Georgia) through the Bosphorus Strait to the Mediterranean and eventually the Suez Canal, a shortcut opened in 1869 that significantly slashed the cost of shipping goods between Europe and Asia.

The Rothschilds had enlisted Samuel to obtain access to his contacts in the Far East but because oil tankers had been deemed unsafe for traversing the canal, rounding Africa and the Cape of Good Hope was the only water route.

Samuel addressed the issue by hiring a British naval architect, James Fortescue Flannery, to design a safer vessel, the oil tanker Murex which in August 1892 completed its maiden voyage through Suez with 4,000 tons of Russian kerosene bound for Singapore.

Russian kerosene could now compete on price with Rockefeller’s US product, prices cratered, and Shell rapidly increased its Asian market share, according to historical sources including Daniel Yergin’s book, The Prize.

The British Colony of Malaysia

In 1910, Malaysia entered the club with Indonesia as a significant center for Asian exploration and production when the now merged Royal Dutch Shell drilled Malaysia’s first oil well near the fishing village of Miri in Sarawak on the northwest coast of British-controlled Borneo.

Miri No. 1, nicknamed “The Grand Old Lady” and preserved today as a state monument, produced 1,950 barrels of oil in its first year after being drilled to a production depth of 452 ft on Miri’s Canada Hill.

However grand she was, The Lady peaked at 83 B/D after reaching a final production depth of 1,096 ft before she was abandoned in October 1972.

Over the ensuing decades, Shell claimed the following series of firsts:

- 1914—Opening Malaysia’s first oil refinery and laying an innovative submarine pipeline to fill tankers anchored offshore from the Miri oil fields.

- 1960—The first mobile drilling unit used in Malaysia, the Orient Explorer, arrived in Sarawak to explore off Baram Point, leading to the discovery of Sarawak’s first offshore field, Baram, in 1963.

- 1961—The first single-buoy mooring is installed offshore Miri.

- 1968—Shell’s West Lutong oil field becomes Malaysia’s first producing offshore field.

- 1971—First oil is discovered offshore Sabah at Erb West.

- 1976—First production-sharing contracts signed for offshore Sarawak and Sabah.

- 1983—Malaysia ships first LNG cargo to Japan in partnership with Malaysia’s national oil company Petronas (incorporated in 1974), Shell, and Mitsubishi.

- 1993—Shell Middle Distillate Synthesis plant commissioned, world’s first commercial gas-to-liquids (GTL) plant of its kind with its expertise later used to develop Pearl, the world’s largest GTL plant in Qatar.

- 2012—Gumusut-Kakap, first production from Shell’s first deepwater project in Malaysia.

- 2015—Malikai Deepwater Project completes record-breaking superlift milestone.

Oil Gives Way to Gas To Fuel Asia’s 21st Century Industrial Revolution

The International Energy Agency’s (IEA) Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2022 notes that Southeast Asia’s 3% yearly average rise in energy demand over the past 20 years will continue to 2030, driven by a doubling of the population since 2000 and an average 5% yearly economic growth rate.

Fossil fuels are projected to meet three-fourths of this demand—primarily gas to replace coal.

As a result, the region is attracting investment—in particular, investment from the UAE—to unlock $100 billion in projects on which final investment decisions (FIDs) are expected to be taken by 2028, according to a recent Rystad Energy report.

The number of FIDs expected are twice the $45 billion announced from 2014 to 2023 and focus on developing recent discoveries in Indonesia and Malaysia including deep water and projects to create a global hub for carbon capture and storage (CCS) such as the one being studied by Petronas and ADNOC.

Malaysia’s move to develop a CCS hub supports its strategy of compensating for the country’s growing consumption of natural gas and development of new gas and oil fields to offset its overall carbon footprint.

This in turn has spurred research into novel methods of converting depleted reservoirs and saline aquifers for CCS use in Malaysia.

Also sensitive to its rising emissions levels, Indonesia has announced it will tender five geothermal sites for possible development by 2025.

Today, Indonesia is Southeast Asia’s largest oil and gas producer, boasting what data and analytics provider Wood Mackenzie called “a steady 6 Bcf/D in gas production over the past 2 decades to offset falling oil output.”

In January, Indonesia’s Upstream Oil and Gas Regulatory Task Force (SKK Migas) announced its intent to bring 15 projects onstream in 2024 at an expected capital cost of $560 million.

These new projects are forecast to generate a total of 41,922 BOPD and 324 MMscf/D of gas, including Medco E&P Natuna’s Forel-Bronang project in the South Natuna Block off the Riau Islands with a production capacity of 10,000 BOPD, The Jakarta Post reported.

Also on the list is ExxonMobil Cepu’s Banyu Urip Infill Clastic project in Bojonegoro, East Java where ExxonMobil began drilling on 27 April as part of a multiyear plan for five carbonate infill wells and two clastic infill wells, according to the The Indonesian Business Post. This would bring on another 30,000 BOPD in production.

In August, Indonesian authorities approved Eni’s plan for integrated development of the ultradeepwater Geng North (North Ganal PSC) and Gehem (Rapak PSC) fields to create the new Northern Hub for production in the Kutei Basin.

Set to go onstream in 2027, the Geng North project boasts an estimated 5 Tcf of gas and is an example of the sort of project exceeding 152 m in depth that Indonesia wants to encourage.

Authorities also approved Eni’s plan for the Gendalo and Gandang fields (Ganal PSC). Additionally, Indonesian authorities have awarded Eni a 20-year extension of the Ganal and Rapak licenses.

In Kalimantan, five deepwater projects are expected to go onstream from 2026 to 2028, according to SKK Migas Undersecretary for Exploitation Wahju Wibowo, whose agency has noted in local media that the country’s investment in oil and gas rose 13% to $13.7 billion in 2023 year-on-year and will reach $17.7 billion in 2024.

UAE’s Mubadala Reaches Significant Exploration Milestones

In September, Abu Dhabi’s Mubadala Energy announced it had won a 40% interest in the Central Andaman exploration license offshore Sumatra together with UK-listed Harbour Energy (60% operating interest).

At the same time, Mubadala confirmed its completion of the South Andaman drilling campaign, with the appraisal of the Layaran discovery having demonstrated the multi-TCF potential of the Andaman Sea basin.

Mubadala also holds a 63% operator interest in the Sebuku PSC with TotalEnergies EP Sebuku and INPEX South Makassar Ltd., each holding a 13.5% interest and PT Dangsanak Banua Sebuku (owned by the Government of South Kalimantan and West Sulawesi) with 10% interest.

In Malaysia, Mubadala has a 55% operating interest in Block SK 320, home to the Pegaga Gas Field Development. Petronas Carigali holds a 25% stake and Sarawak Shell Berhad 20%.

Indonesia is aiming to boost its oil and gas production to reach targets of 1 million BOPD and 12 Bcf/D of gas by 2030 with 54 potential onshore and offshore oil and gas blocks on offer over 2024–2028 focused on untapped areas such as the South Sumatra Basin.

Malaysia has its sights set as well on untapped areas, but its biggest potential largess lies in waters of the South China Sea where overcoming technological obstacles are only a small portion of the challenge.

Malaysia’s Energy Dispute With China in the South China Sea

For nearly two centuries, Southeast Asia has been central to global energy politics: from the “Game of Thrones” between Europe’s colonial powers in the 19th and early 20th centuries, to World War II and Japan’s first troop landing in Borneo, to the Cold War standoff in Indochina involving the US, Soviet Union, and China, and now to the high-stakes geopolitical maneuvering by regional and global powers in the South China Sea.

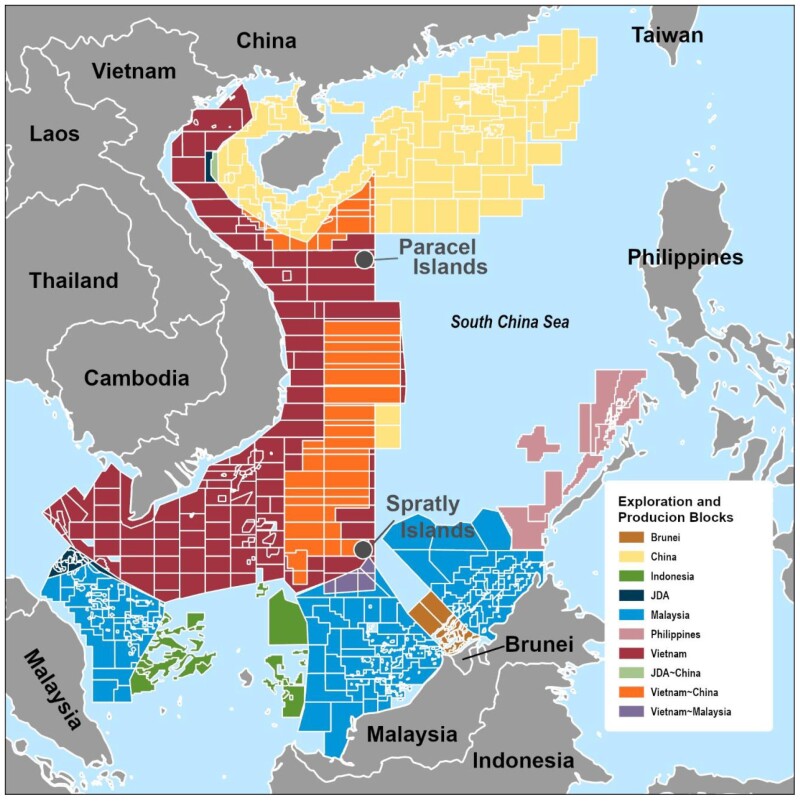

In a diplomatic note from China to the Malaysian Embassy in Beijing dated 18 February, China had asked Malaysia to stop all exploration and drilling in the South China Sea, even in Malaysia’s own Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

This would include the Luconia Shoals 100 km offshore of Sarawak (2000 km from China) and arguably part of the Spratly Islands to which China, Taiwan, Malaysia, Brunei, Vietnam, and the Philippines all lay claim.

In an opinion piece published by NikkeiAsia in September, Phar Kim Beng, CEO of the Malaysian consultancy Strategic Pan Indo-Pacific Arena, pointed out that “it is clear that Malaysia and China have a serious bone of contention … especially (over) the Kasawari gas development projects that began in 2012 at Luconia Shoals.”

The China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC) announced in August it had confirmed more than 100 Bcm (3.5 Tcf) of proved gas reserves at the Lingshui 36-1 offshore field southeast of China’s Hainan Island province, making the prospect the world’s first major ultrashallow gas field discovered in ultradeep waters.

Beng quoted Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim as telling a news conference during the Eastern Economic Forum in Vladivostok, Russia, in September that Malaysia “will have to operate in our waters and secure economic advantage, including drilling for oil, in our territory.”

But far from being fighting words, Beng argued that China’s demand was more about pushing Malaysia to agree a code of conduct on the South China Sea which is currently under discussion within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

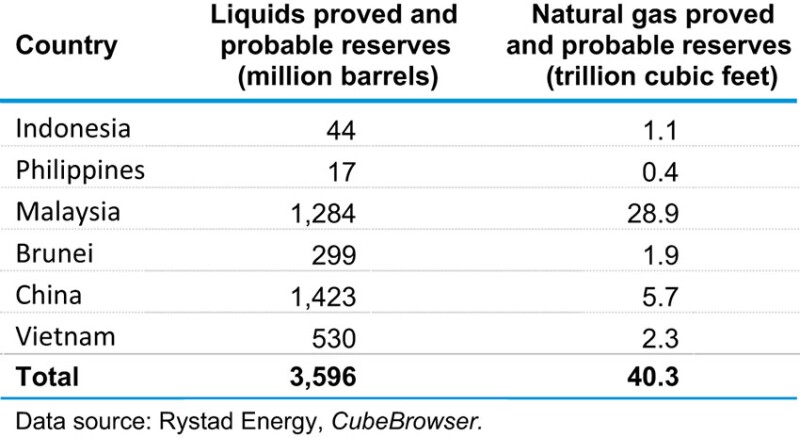

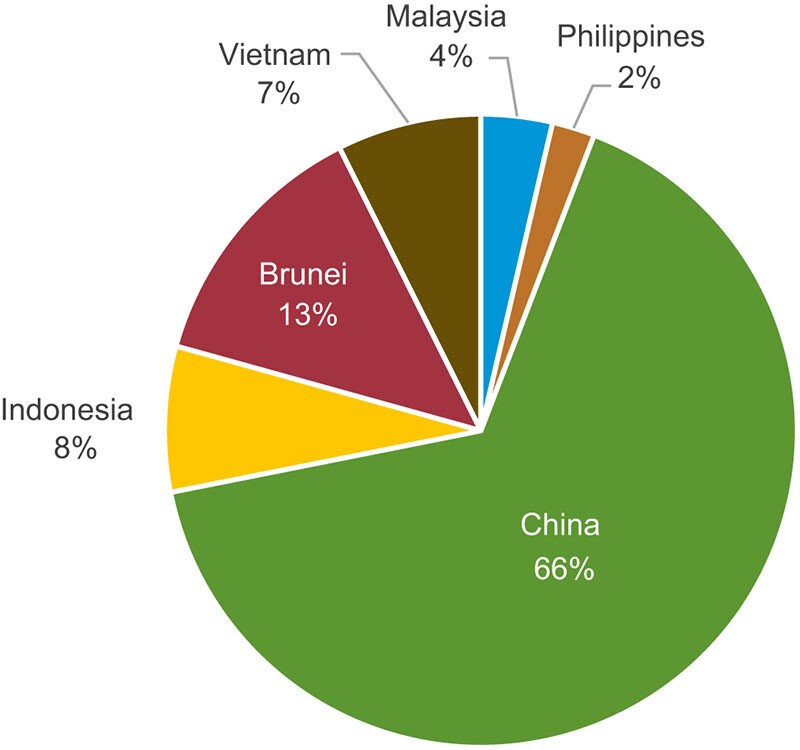

Territorial disputes are a major reason that the South China Sea remains largely unexplored. What has been discovered is near to shore, amounting to about 3.6 billion bbl of petroleum liquids and 40.3 Tcf of proved and probable reserves of natural gas, according to Rystad Energy data quoted in a US Energy Information Administration (EIA) Regional Analysis Brief in March.

For Further Reading

Royal Dutch Shell: A Brief History by Trude Meland, Norwegian Petroleum Museum.

The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power by Daniel Yergin.

OTC 34901 Energy Recovery From Geothermal Reservoirs in the Baram Basin, Sarawak: A Numerical Reservoir Simulation Approach With CO2 Utilization by M. Bataee, Curtin University; M. Soh, Reservoir Minds; and J.B. Ruvalcaba, Baker Hughes; et al.

OTC 32923 Studying Affecting Factors in Geothermal Energy Production From Depleted Oil Fields of Onshore Sarawak, Malaysia by M. Bataee and S.W.J. Tan, Curtin University; and R. Ashena, Asia Pacific University of Technology and Innovation, et al.