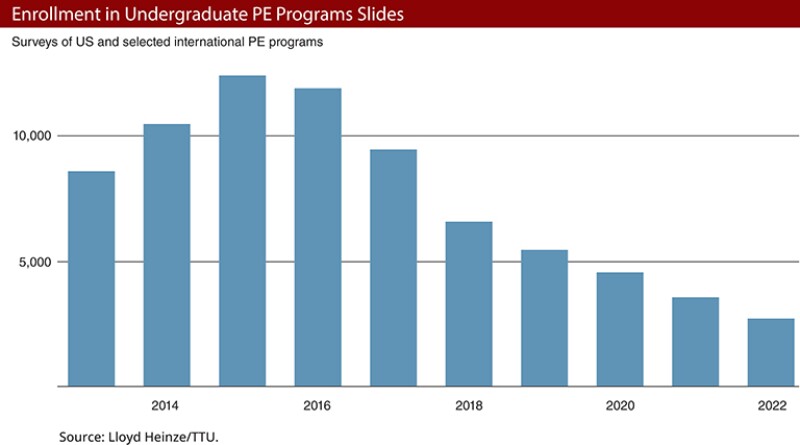

For the seventh year in a row, the number of undergraduates in petroleum engineering (PE) programs is down, but that could be changing.

Over the next year, Lloyd Heinze, a PE professor at Texas Tech University who has long done the survey discussed here, sees this downward trend slowing and then stabilizing in the next couple of years. There is no sure way to predict which majors undergraduates will pick, but there are some long-standing patterns to consider.

Based on past long slumps for US programs, the decline line is nearing a point where it stabilizes at a low level for years, and when the industry lives off the surge in PE graduates that occurred during the previous boom years.

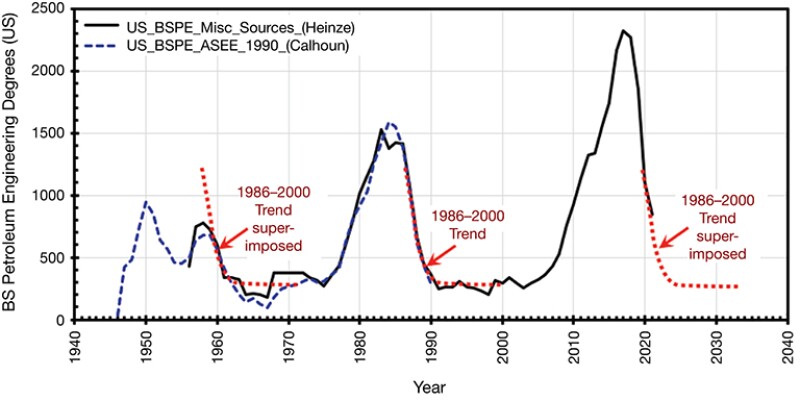

But there is another trend that could change things. There has always been a strong relationship between class sizes and the preceding increases in oil price. The recent surge in oil prices to more than $90/bbl could signal a rebound, as it did early this century when it helped end the slump that dated back to the 1980s.

If those two trends apply, it could mean “there will be fewer bachelor’s degrees awarded this year, and after that we will be back to growing ever so slightly. And then 2 years from now we will be overwhelmed,” by new students, Heinze said.

So far, the survey is not offering evidence of a change from the down trend.

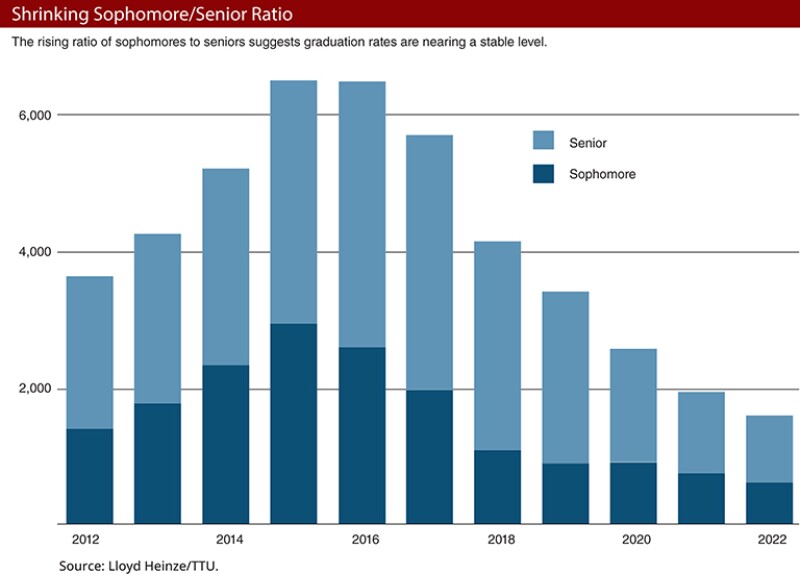

The best indicator of the size of future graduation classes is the level of undergraduate enrollment. During the slide down, the number of seniors has been far greater than the number of freshmen.

This year’s class shows that gap has narrowed. To stabilize it, the number of freshmen will need to far exceed the size of the senior class because another pattern is at work.

Heinze said the number of freshmen and sophomores who say they will major in petroleum engineering drops by 30% per class year as these students realize what is required, which includes proficiency in calculus.

Hiring Drives Enrollment

While it is hard to deny the power of higher oil prices to increase oil industry activity, Heinze and others in academia contacted for this story point out that the ultimate driver is the industry’s appetite for new engineers.

Students and their parents are looking for signs that the hard and costly job of getting a PE degree is rewarded with a job and a salary that justifies the effort.

So far, those in PE programs are seeing an improved job market with demand for the graduates they are supplying. When Texas A&M announced a spring job fair, there was a strong response from potential employers, said Tom Blasingame, a professor of petroleum engineering at Texas A&M and 2021 SPE president. He said the market is much improved for students seeking jobs, but it is not like the boom days when multiple offers were common.

“I do not believe that oil prices are going to help us significantly in increasing the enrollment,” said Mohan Kelkar, chairman of the McDougall School of Petroleum Engineering at the University of Tulsa, who sees oil companies sticking to conservative spending programs.

There is also the possibility that the wave of graduates hired during the first half of the past decade will suppress demand for years to come, as it did during the 1980s hiring bust that continued for about 15 years. During those low-oil-price years, the prevailing theme was layoffs.

Hiring picked up early this century as oil prices began to improve and the retirement en masse of baby boomers began the great crew change. Still, it is hard to explain the peaks based on supply and demand.

“The peak in the early 1980s was too high and the last peak was almost twice that high; neither of those was justified,” Heinze said.

The great crew change has ended, but it is hard to know how many of the engineers caught in the past PE graduate bust are still looking for work in the industry.

The consensus among the experts is that many of the graduates from the peak years found other industries that valued their skills. If that hard-to-measure observation is true, it should ensure there are jobs for future graduates.

“Unfortunately, I think a lot of them left the core E&P industry. While many stayed in the oil business, we lost a lot of talent,” said Jennifer Miskimins, professor and department head of petroleum engineering at Colorado School of Mines.

For PE majors, this also suggests they should acquire marketable skills relevant for employers outside of oil and gas, though there are probably easier ways to learn those than earning a PE degree.

Oil Demand Abides

PE schools are also battling the widespread assumption that the rapid growth of alternative energy sources will lead to a rapid phaseout of oil and gas.

That is not the case based on long-term outlooks from respected sources such as the US Energy Information Administration that say the current levels of oil and gas production will be needed to meet the demands of rapidly growing countries, particularly in Asia.

But talk of a rapid decline in the industry dogs those working to recruit top students to PE programs.

“Students are reluctant to enter into a field where they do not see a bright future,” Kelkar said. While he and others say petroleum engineering is still a well-paid career option, “attracting these students to a PE program is a challenge.”

The US shale industry is not likely to be the job creator it was a decade ago when independents were racing to put their acreage into production, creating an enormous amount of work for new petroleum engineers.

Much of that exploration and evaluation work is in the past, and automation has eliminated some labor-intensive technical jobs. As a result, the number of entry-level hires needed is lower, but the number of PE graduates is also much lower.

International oil looks slow and steady as OPEC sticks to a slow-growth strategy likely to maintain higher prices.

While the international programs in the 26-university survey by Heinze have also seen declines, they are more modest ones because they limit their program growth based on the expected hiring needs of national oil companies.

One reason to assume disciplined production lies ahead is the number of OPEC members not meeting their production quotas, suggesting they will be spending more to develop their resources. That will create opportunities internationally.

“They [graduates] have got to move to regions where the job market is for technical people—engineers and geologists,” Heinze said.

US students seeking those jobs, though, will be competing with graduates from international PE programs.

In 10 years, Heinze predicted more PE students “will be getting degrees outside the US than inside it.” That year is likely to pass unnoticed because there is no global count of PE programs.

Heinze gathers data from programs that are accredited by an organization known as ABET that expanded its original role at US universities. ABET is a nonprofit, ISO 9001-certified organization that accredits college and university programs in applied and natural science, computing, engineering, and engineering technology. Heinze said there is a universe of institutions that is not required to report its enrollments.

While the US has obsessed on shale production, Heinze said those in the US looking for international opportunities can benefit from knowledge of the Permian Basin and giant conventional plays. That knowledge can be applied to international fields that have been developed more recently.

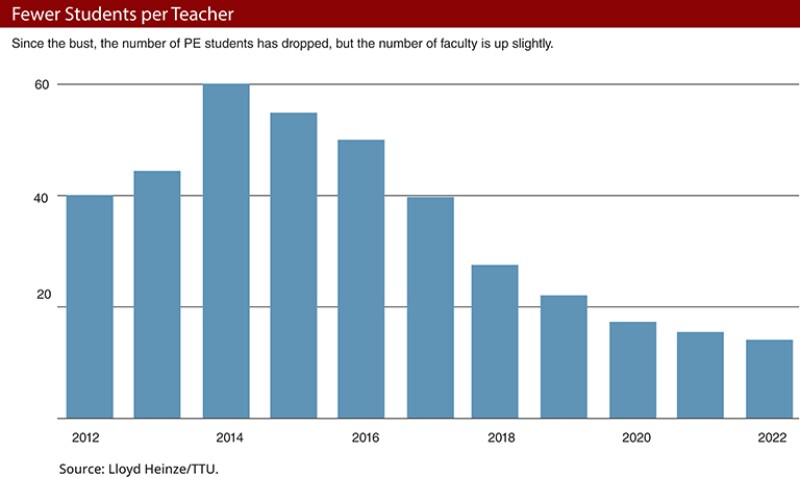

Those enrolling now are more likely to get a chance to get to know their professors because the ratio of students to faculty at the schools surveyed has dropped from more than 60:1 to 14:1—the lowest it has been this century.