This is the final article in a series of six on SPE’s Grand Challenges in Energy, formulated as the output of a 2023 workshop held by the SPE Research and Development Technical Section in Austin, Texas.

Described in a JPT article last year, each of the challenges are discussed separately in this series: geothermal energy; net-zero operations; improving recovery from tight/shale resources; digital transformation; carbon capture, utilization, and storage; and education and advocacy.

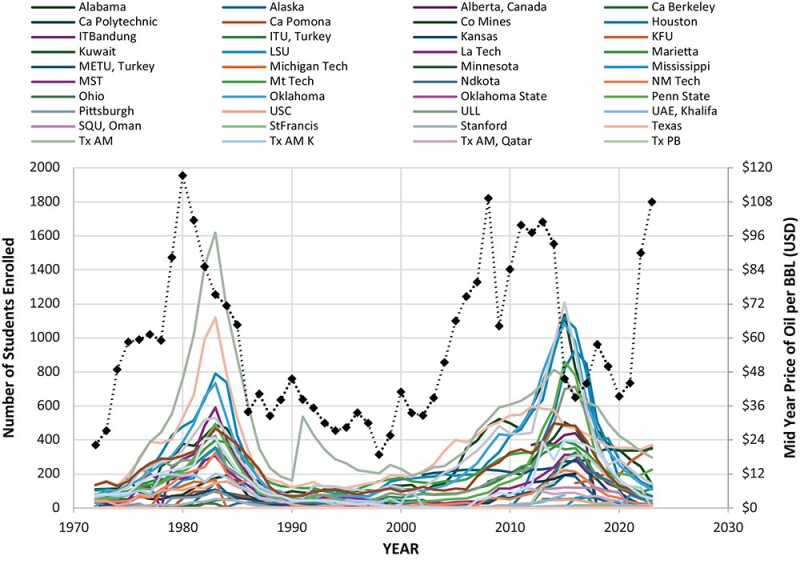

We have our work cut out for us… but then, we always have in our industry. Following the crippling effects of the oil embargo in 1973, the price of crude oil climbed high and fast to the top of the charts. That increase in crude oil value brought students to petroleum engineering programs in droves around the world. It was not just the crude; it was the value of the degree program. Students rightly saw an opportunity to work in an industry that fueled the engine of the global economy, lit their homes, warmed their food, and moved people around the continents, all reliably and affordably.

The post-embargo peak in enrollment was only topped by the peak following the shale boom of the mid-2000s. After the post-embargo boom in the 1980s came the bust. Similarly, many of us were not left standing when the mid-2000 boom busted. The price of oil is climbing again; natural gas and crude oil use is up and consistently so, but the petroleum engineering enrollments are not (Fig. 1).

Depending on where you started along the x-axis in your career (Fig. 1), you may already know this story. What’s different now in an industry known to be cyclical, where we’ve seen this before? If higher crude oil prices and concomitant salaries are not bringing in the students, what will?

The demand for STEM graduates is high across industries, and it’s particularly acute in the oil and gas sector. The US faces a significant shortage of STEM graduates to meet the needs of critical industries. This scarcity raises concerns about our ability to fill specialized roles, such as petroleum engineering, which are crucial for the energy sector’s development over the next century. If we struggle to produce enough STEM graduates overall, how can we expect to meet the specific demands of the oil and gas industry in the coming decades?

There are a few reasons for this new trend. More than half of Americans say that STEM studies are too hard and nearly a quarter believe that STEM studies are not useful for a career. The National Academies have been sounding the alarm for more than 20 years about where we are going technologically, as a nation, and who is going to get us there.

Second, within STEM degrees in general, there are fewer petroleum engineering, or equivalent graduates. While additional energy types in the mix have been growing for years, the sharp move toward renewable energy and simultaneously painting hydrocarbons as undesirable is recent.

Third, recent graduates want meaningful work. That new employees want meaningful work is not a new idea, despite more recent generations laying claim. How one defines meaningful work will be as varied as the number of people asked the question. One significant metric is energy security.

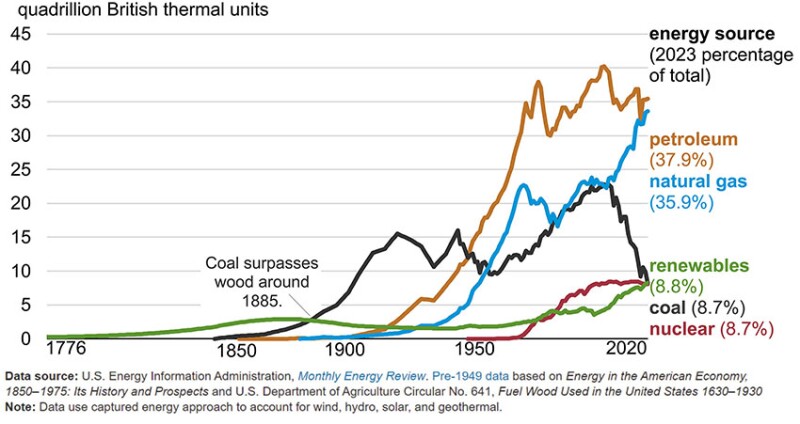

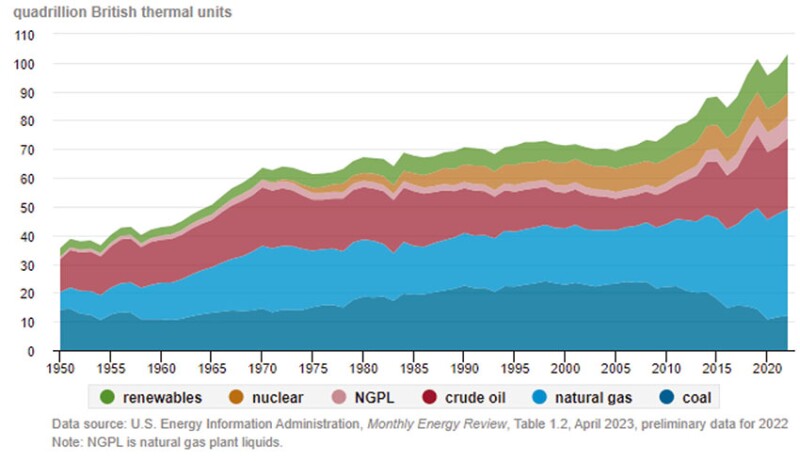

Energy security is national security. Energy independence is energy security. And a reliable, affordable, safe, and diverse energy mix ensures energy independence. Looking at Fig. 2, the US uses energy from a variety of sources. Energy consumption can and should be fit-for-purpose. Ensuring that our families and neighbors have heat in the winter, electricity for food storage and hospitals, and fuel for transportation is energy security.

The value of the degrees taught in our universities will not be tied solely to a paycheck (to be clear, I am a strong advocate for understanding student loan debt, one’s responsibility and capacity for repaying that debt and building a comfortable future for oneself and one’s family). Careers in the energy industry are meaningful and generally come with salaries that match the investment one makes in one’s education. The persistence of this trend could lead to the closure of additional petroleum engineering programs, potentially jeopardizing the future workforce for this critical sector.

Let’s go back to Fig. 1. The first wave of students coming into these programs did not have the advantage of social media. Students found out about the opportunity, the route to success, and the careers largely by word of mouth. Fast forward to the early 2000s when the second uptick started. Although there were some sites, use was not extensive. Myspace began in 2003, Facebook in 2004, YouTube in 2005, Instagram in 2010, and TikTok in 2016, to name a few.

This means that the bulk of students who matriculated into these programs would have come in on the advice and recommendations of parents, family friends, or schoolteachers; possibly by job searches for careers with higher salaries; college fairs in high schools; or by living in an oil town.

In short, it was word of mouth.

And this is what we will need to do again: educate and advocate.

Not only will members of industry—corporate and individual—need to invest in programs designed specifically for students, but we also need to include educating K-12 teachers as well. Currently, some programs led by individuals, or others as part of a workshop, are driving toward this end. These efforts, though, are too thin and disparate to affect the needed sea change in thinking.

We have a wonderful story to tell.

First, the industry is not going away for the next 50 to 100 years. The career you build in petroleum engineering will see you through the finish line. Americans—and citizens of planet Earth—are not now nor will they ever use less energy. Our energy needs are only going to grow and right now we are running to stand still with energy production.

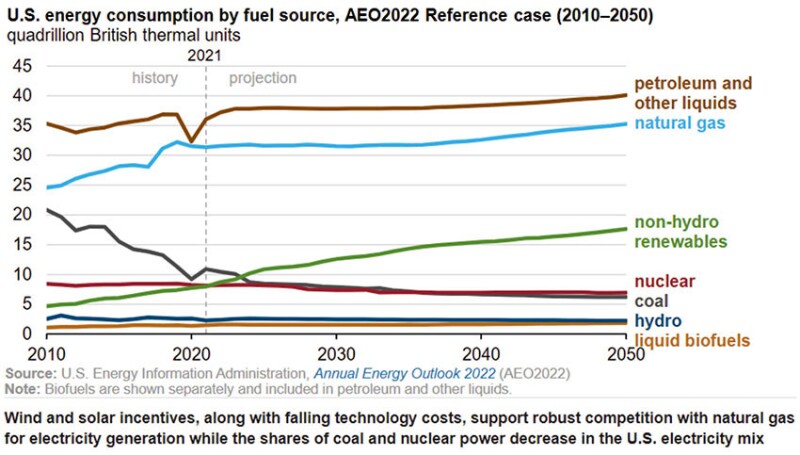

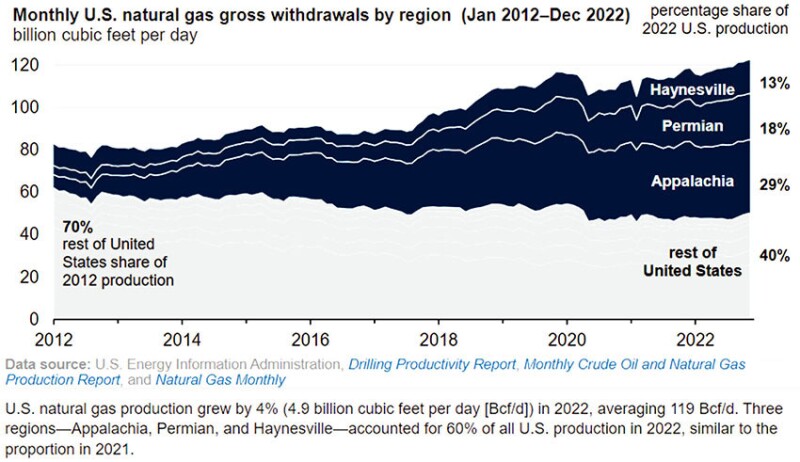

Even with the increase of other types of energy, natural gas production is still growing because there remains a market for it (Figs. 3, 4, and 5). The advantages of natural gas, its affordability, reliability, and safety are well known and understood. Infrastructure is already in place in much of the world, which means it will be in use for a long time to come.

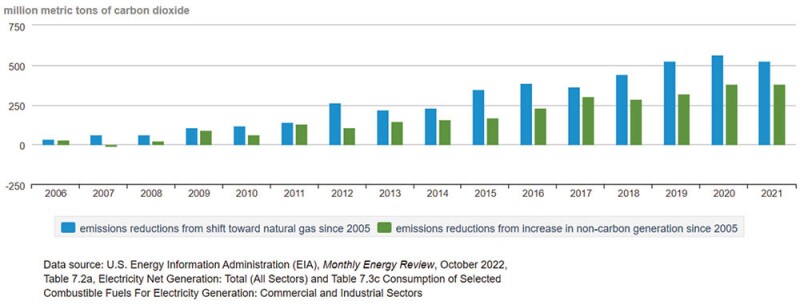

Second, switching much of our power generation to natural gas has demonstrably decreased our CO2 emissions (Fig. 6) … more than the UK, Ukraine, Japan, and Germany—the next four emitters combined (Why the U.S. Leads the World in Reducing Carbon Emissions, Forbes 2024).

Third, as you’ve read in prior Grand Challenges articles, the skills learned through a petroleum engineering degree or equivalent are transferable to other energy sector careers. This livelihood is not limited to one job description only. Whether the decision is to move up and down the oil and gas stream or jumping over to carbon capture, utilization, and storage or geothermal work, the opportunities are consistent and tremendous.

There is no simple answer, which means there is no single solution. What is needed is a concerted, multi-pronged approach.

- Industry: We need investment in workshops to provide K-12 teachers with the opportunity to learn about the energy industry and receive continuing education credits; continue partnering with academia for student internships; and provide travel support both for professors and students to industry technical conferences.

- Professional Societies: We need members to work with high schools and college campuses to promote career opportunities and the benefits of earning a STEM degree. We also need to provide tools to our members so they can actively engage with high school and college campuses.

- Individuals: We need active outreach with middle school-aged students to encourage strong leadership in STEM studies.

None of what is written above is particularly new or revolutionary. Similar to the question asked at the beginning of this article, what’s different this time around? The difference is that there is a desperate shortage of qualified professionals now and for the foreseeable future. No longer is a high salary enough. New and future employees want work that makes a difference and careers that provide a measure of stability.

While the actual job may come and go, the skills and experience in this industry are transferable within the oil and gas stream and into adjacent energy sectors. We have that story to tell and tell it we should. Educating those around us will improve the general energy literacy of those making decisions. Having conversations with our local and state officials so they know who to turn to when they have questions about energy policy will have a real impact. Asking already overburdened individuals to contribute their time and energy to a middle school science fair is a lot, but it can mean one more STEM student a year graduates and joins our ranks. Integrating that one small act will have a profound impact on our much-needed workforce.

Our industry has been counted out before. We dug in and we made incredible technological advancements that redefined maps, state budgets, and US energy independence. We need that same grit, that same determined attention to this goal, and we will see what we know to be true: our industry is resilient, needed, and worthwhile.

The past few years taught us to be lean, precise, and focused. Combining that discipline with the plan outlined above will deliver the results we need to see our industry, our nations, and our planet safely—securely—into the next century. It is time to educate and advocate.

For Further Reading

Energy Exec Emphasizes Core Petroleum Engineering Skills by Jennifer Pallanich, JPT.

From Classroom to Oil Patch: Attracting the Next Generation of Petroleum Engineers by Jennifer Pallanich, JPT.

Scyller J. Borglum, PhD, SPE, has more than 15 years’ experience working in upstream, midstream, and adjacent energy industries including geomechanical laboratory research. She is currently vice president of energy and underground storage for WSP USA. Borglum is a passionate advocate for bringing new students into STEM studies, particularly energy production, generation, development, and storage. She is the author of “STEM Study Habits: Successfully Navigate Math, Science, Engineering, and Life for Your Degree” which helps prepare STEM students for success in their undergraduate, graduate, and post-graduation life.

Arash Dahi Taleghani currently serves as a professor in the John and Willie Leone Family Department of Energy and Mineral Engineering at Penn State University. His research interests lie broadly at the intersection of geomechanics and material science with emphasis on subsurface energy systems, (i.e., innovation in cementing/sealing materials, energy storage, and geothermal systems).