The job market is looking up for petroleum engineers graduating this spring.

With oil prices up, companies are hiring, which means most of the shrinking number of graduates have already lined up jobs, according to Lloyd Heinze, a professor at Texas Tech University, who does an annual survey of petroleum engineering (PE) programs.

At Texas Tech, he said more than 90% of the students already have jobs upon graduation, with most of them going to work for operators.

Demand is also strong for graduates at Colorado School of Mines, Penn State University, and Texas A&M University, where most of the seniors have jobs arranged in advance of graduation.

Tom Blasingame, a petroleum engineering professor at Texas A&M, and 2021 SPE president, said the career fair held last fall “was very well attended, and I believe our placement percentage will be very high in 2023.”

He said 80% of students who graduated from A&M in December had jobs lined up, and he expected they would all have jobs within 2–3 months of graduation.

Jennifer Miskimins, a professor who is head of the petroleum engineering department at Mines, agreed that the hiring rate is at that level, with some students getting job offers after completing summer internships.

Sanjay Srinivasan, department head at the Energy and Mineral Engineering Department at Penn State, said hiring demand “looks much better this year than last year. However, we are concerned that many of the oil and gas companies that come on recruitment visits seem more interested in talking to graduates from other departments like mechanical and chemical engineering.”

Others are seeing the same trend. “The supermajors will take the engineers and train/mold them into whatever they need,” Miskimins said. Blasingame added that independent operators, however, focus on petroleum engineers because they “don’t have extensive training programs like supermajors, so they hire the people who can ‘work on day 1.’ ”

Also, Srinivasan said companies are increasingly selective. “I feel that the companies have lean recruitment targets and so they basically shop for the best-fit graduates from multiple schools,” he said.

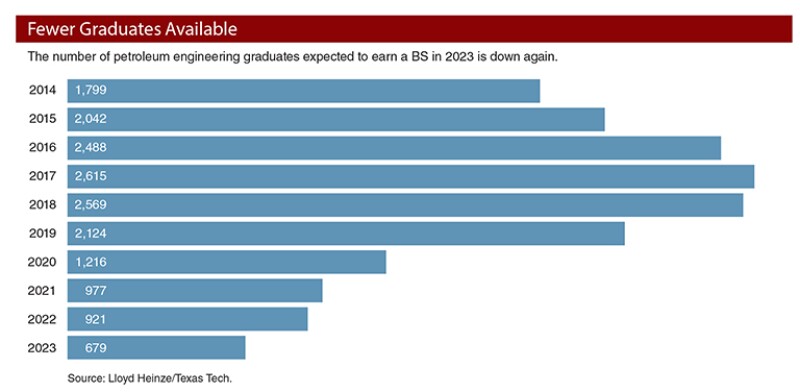

It is a striking turnaround from a few years ago when record numbers of students flooded a weak job market, looking for any oil industry job they could find or looking outside the industry to companies that valued their math and science skills.

Still, given the high price of oil, hiring demand that is equal to a shrinking supply feels odd to Heinze and the others. Based on their experience, when oil prices hit $100/bbl, the demand for PE grads and enrollment go up.

Something Heinze finds “spooky” this time around is that oil companies are not complaining about the small size of the graduating classes.

It feels odd to Heinze because in the past when prices were high and activity picked up, college administrators heard complaints from oil companies such as “How many (seniors) do you have?” and “We need more.”

“We are seeing the same, very good placement. However, I have had companies tell me that they aren’t making their hiring goals,” Miskimins said.

She is not hearing complaints about the graduation rate “but definitely concerns.” To address the problem, Mines has hired a direct recruiter as part of an effort to attract more earth sciences students, Miskimins said.

Down, Then Flat

Based on the enrollment at freshmen and sophomore levels, the trend is not likely to improve. Based on those numbers—which are iffy as a freshman’s career plan—it looks like enrollment is about to hit bottom and remain there for a while. This is similar to a pattern in the 1980s when PE enrollment bottomed out at a low level which lingered for years.

“Like Lloyd mentioned, companies don’t seem to be concerned about low enrollment and graduation numbers, but we have seen this before, as well in the late 1980s/early 1990s,” Blasingame said.

A big difference from that protracted slump is that oil and gas prices are back up to where they were before the bust, hitting $100/bbl.

But things are different now. For one, when adjusted for inflation, $100/bbl today would have been worth about $80/bbl in mid-2014. And lately, Brent crude has been trading in the $80s, which inflation-adjusted would have looked painfully low in 2014.

A bigger issue for hiring has been the slow‑growth strategies of oil companies. The industry is limiting spending on exploration and development. Management is acting as if the companies will be part of a huge, highly profitable industry with little or no growth.

Most of the majors have pared oil and gas operations, allowing them to focus on low‑carbon alternatives, some of which will create opportunities for engineers.

Once fast-growing independents in the US shale sector are also keeping a tight leash on spending, focusing on profit maximization and investor returns rather than growth. Limits on the services side, such as drilling rigs and fracturing spreads, are making more rapid expansion expensive.

Declining PE graduation rates will test how low oil company hiring can go.

The 25 schools responding to the survey expect to award 655 BS degrees this year, down from 894 in 2022. Both look low compared to the record peak of 2,615 grads in 2017.

Next year’s graduation class looks to be around 500, based on the 587 students who are now juniors.

This year’s senior class totaled 800 students while there are only 587 juniors. The gap is not as large as it appears because the number of seniors is inflated because many schools define a senior as a student who has accumulated at least 90 hours of credits. Given the heavy course loads required to earn a PE degree, that measure includes many who are still in their third year of college, which has led Texas Tech and other schools to find more accurate measures.

The number of master and PhD degrees awarded will also be down this year.

“We are back to the early 1990s in terms of our graduate program size” and its growth outlook, said Blasingame, who added that is “very concerning.”

Good, Not Great

College students are picking majors at a time when the unemployment rate is at a record low, so there are other high-paying careers to choose from when there is a lot of talk about phasing out oil and gas.

At Mines they are working to remind students that PE skills are needed to keep up with future oil and gas demand in the decades ahead, as well as provide necessary skills for new fields from carbon storage to geothermal energy.

“We have a very active recruiting program going on right now along with our Mining, Geology and Geophysics Departments—reminding incoming students that earth sciences are still very much needed,” Miskimins said.

At Penn State the typical PE student, and what they study, is changing.

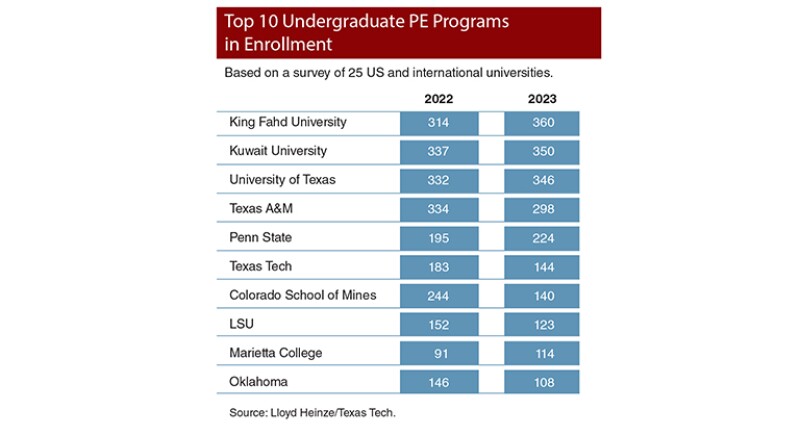

“We have a fairly steady influx of students from overseas (Middle East, China, etc.) that props up our enrollment,” Srinivasan said.

“Many of our students also equip themselves with a minor in energy business and finance that is also offered in the same department. We also feel that there may be some pent-up demand for PE minors and are actively considering strategies to roll out the minor,” he said.

Programs are competing for the limited pool of students with strong math and science skills with a number of other attractive tech career options.

One factor that may be limiting hiring is that the last oil boom sent a huge wave of young petroleum engineers into an industry that needed to rapidly replace the baby boomers who had been hired in the early 1980s boom and were nearing retirement.

While many of those struggled to find jobs after the 2014 price crash and left the industry, those who survived are now experienced engineers within companies that have been working for years on getting more out of less.

Saudi Arabia Leads

Once again, the Middle East is the most powerful force in the oil market, and it has also become a force in petroleum engineering.

The two biggest petroleum engineering programs based on undergraduate enrollment are now King Fahd University in Saudi Arabia, followed by Kuwait University.

Both reported gains allowing them to move ahead of the University of Texas, which was up a bit, and Texas A&M which dropped.

The number of programs responding in time to be included in the survey—which was provided several months after it was sent out to the schools—dropped to 26 from 27 last year. Those missing are mostly international institutions.

The footprint of this survey amounts to a fraction of the world represented by the Society of Petroleum Engineers.

Most of the universities surveyed are in North America, which represents 10% of the members of SPE student chapters in the world. Even if chapter members from the Middle East are included because a few schools are sampled in that region, these two regions would only represent about one quarter of all student members.

While chapter membership is at best a rough indicator, the survey’s limited geographic coverage has long been a concern for Heinze, who has struggled to get data from institutions that are not part of ABET, the accreditation body for US PE programs and some international ones, which requires disclosure.

An international source of data is the Higher Education Statistics Agency, which collects UK university data. It showed enrollment dropping in 2021 to 245 undergraduates, down from 385 the year before and a peak of 1,740 in 2014. Graduate level students dropped from 385 in 2020 to 245.

The Heinze survey showed that as student bodies shrink, so does the number of teachers. The faculty count dropped from 340 in 2022 to 293 last year. Because the decline in student numbers means the ratio of teachers to students is also going down, schools have little reason to hire.

Heinze said he has not heard of any layoffs and suspects the decline might include older professors, like himself, who have retired.

Blasingame wonders who would teach the future petroleum engineers.

“The point about faculty reduction is critical; some programs have only very junior and very senior faculty. This could lead to significant difficulties in research, in teaching, but also in training,” he said, adding, “We don’t use the word training much in academia, but we really do train the next generation of faculty there.”