It wasn’t too long ago that Arctic oil and gas exploration enjoyed celebrity status as the industry’s last frontier, chock full of gigantic unexplored hydrocarbon deposits just waiting to be developed.

Fast forward and less than a decade later, the same climate change that made Arctic oil and gas more accessible has caused an about-face as governments and the world’s supranational energy companies rebrand and target control of greenhouse gases (GHG) to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

Among countries with Arctic coastlines, Canada has focused its hydrocarbon production on its oil sands which sit well below the Arctic Circle; Greenland has decided to not issue any new offshore exploration licenses, and while Norway is offering licenses in its “High North,” the country can’t find many takers.

The Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) reported that while 26 companies applied for licenses in 2013, this year’s bid round attracted only seven participants.

Norway is Europe’s largest oil producer after Russia with half of its recoverable resources still undeveloped and most of that found in the Barents Sea where the NPD says only one oil field and one gas field are producing.

That leaves Russia and the US—geopolitical rivals which are each blessed with large Arctic reserves and the infrastructure to develop those riches—but whose oil and gas industries play different roles in each nation’s economy and domestic political intrigues.

Russia sees its Arctic reserves, particularly gas reserves, as vital to its national security, considering that oil and gas accounts for 60% of Russian exports and from 15 to 20% of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), according to Russia’s Skolkovo Energy Centre.

With navigation now possible year-round along the Northern Sea Route, Russia’s LNG champion and its largest independent gas producer, Novatek, is moving forward with exploration to expand its resource base and build infrastructure to ship product east to Asia and west to Europe.

As a result, Russia’s state-owned majors—Rosneft, Gazprom, and Gazprom Neft—are lining up behind their IOC colleague as new investment in Arctic exploration and development is encouraged and rewarded by the Kremlin.

In contrast, the American Petroleum Institute reports that the US oil and gas industry contributes 8% to US GDP, a statistic that enables the US to have a more diverse discussion than Russia about the role that oil and gas may play in any future energy mix.

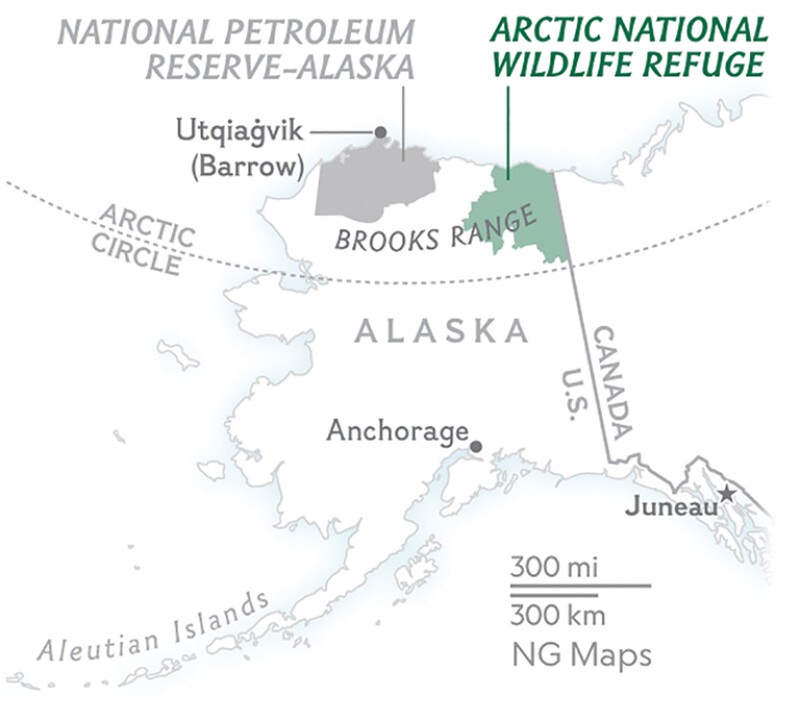

That is unless you happen to be from the state of Alaska where US Arctic oil and gas is synonymous with Alaskan oil and gas, and where the US Geological Survey estimates 27% of global unexplored oil reserves may lie.

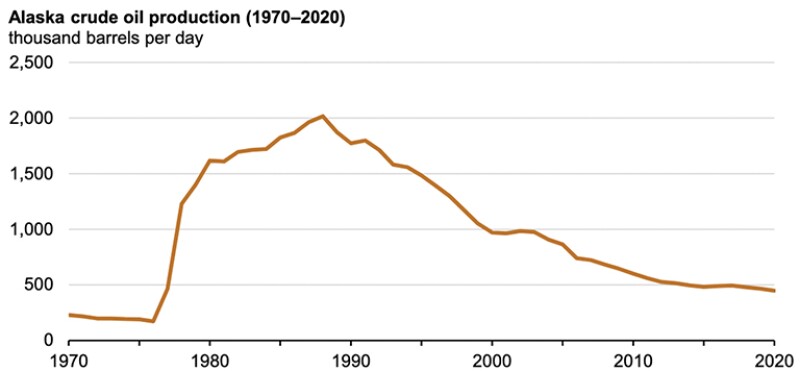

Though Alaska is responsible for only 4% of US oil and gas production, those revenues covered two-thirds of Alaska’s state budget in 2020 despite the state’s decline in crude production in 28 of the past 32 years since it peaked at 2 million B/D in 1988, according to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA).

In 2020, Alaska averaged 448,000 B/D in crude oil production, the lowest level reported since 1976, the EIA said. The steady decline reflects the maturing of Alaska’s production areas and the lack of exploration and development of new license areas to bring additional production on stream. This is even though, compared to most basins, Alaska is relatively underexplored, with approximately 500 exploration wells on the North Slope, according to the Alaska Department of Natural Resources.

In Alaska, the future of US Arctic hydrocarbon production is knotted up in a tangle of federal court cases and executive orders by the Biden administration intended to reverse Trump-era initiatives that sought to enable new oil and gas exploration and production projects on federal lands.

In August, Alaska’s largest oil and gas producer, ConocoPhillips, announced it would likely delay a final investment decision (FID) expected this year on its North Slope Willow project, after the US District Court of Alaska blocked the project by vacating environmental assessments previously approved by the Bureau of Land Management and the US Fish and Wildlife Service.

The court ordered both agencies to reevaluate the project’s effect on GHG emissions along with its impact on wildlife, and reissue new findings before the project can move forward.

The Willow project in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, west of Prudhoe Bay, was slated to begin production in 2027, assuming ConocoPhillips declared the $6-billion FID by yearend, the company’s Senior Vice President Nick Olds said in a 30 June investors call.

In that call, Olds called Willow the company’s “next great Alaska hub” with 200 wells and a processing plant to support 180,000 B/D of production. He added, however, that the schedule would depend on final resolution of the court case.

Significant oil exploration and development opportunities still exist on the North Slope, with 75% of the exploration portfolio undrilled.

Olds said Conoco Phillips expects to eventually develop Willow but an FID won’t be made until legal risks are mitigated. The Biden administration has supported the project, which was green-lighted during the Trump administration, even as the new administration seeks to undo its predecessor’s other initiatives to allow exploration and development of Alaskan oil and gas.

Biden Backs Willow But Says "No" to New Leases

In more court action in August, the White House filed an appeal in the 5th US Circuit Court of Appeals in New Orleans to overturn a lower court ruling that had rescinded Biden’s executive order of 27 January to impose a moratorium on oil and gas leases allowed under the previous administration on federal land and waters.

Louisiana’s attorney general, together with officials in 12 other states including Alaska, sued in federal court in March to overturn the Biden order and on 15 June, US District Judge Terry Doughty in Lafayette issued an injunction, ruling in favor of the states and against the federal government.

The Interior Department had already canceled oil and gas lease sales from public lands through June—affecting Alaska, Nevada, Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, and the bureau’s eastern region, according to the Associated Press.

Meanwhile though, the Alaska Industrial Development and Export Authority (AIDEA), a state-owned economic development corporation which had bought seven of the nine oil leases auctioned in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) before Biden took office, has fast-tracked implementation of a $1.5-million pre-exploration workplan to develop its leases regardless of any federal moratorium.

The AIDEA approved the expenditure in June, 2 weeks after the Interior Department issued its license cancellation order. On 4 August the state authority reported on its website that it had awarded a contract to SAExploration Inc. to perform predevelopment permitting and planning work including impact studies, data collection, and regulatory permitting to support a phased, multiyear seismic acquisition program targeted to begin in 2022.

In a statement on its website, the AIDEA contends that the moratorium is not legally valid, an argument that seems to have been reinforced by Judge Doughty’s decision in the case brought in Louisiana.

And in a letter sent on 11 June to the Interior Department, the AIDEA said it holds “valid and enforceable leases covering 365,775 acres onshore” that grant the AIDEA “legal, exclusive rights of access” to explore and develop any reserves there.

The AIDEA noted that the non-wilderness Section 1002 Area of the ANWR where its leases are located contain an estimated 7.6 billion bbl of recoverable oil and 7.0 Tcf of natural gas.

Is a North Slope Renaissance in the Works?

In January 2020, the Alaska Oil & Gas Association (AOGA) commissioned the Alaska-based McDowell Group (now McKinley Research Group LLC) to prepare a study of the impact of oil and gas on the state’s economy.

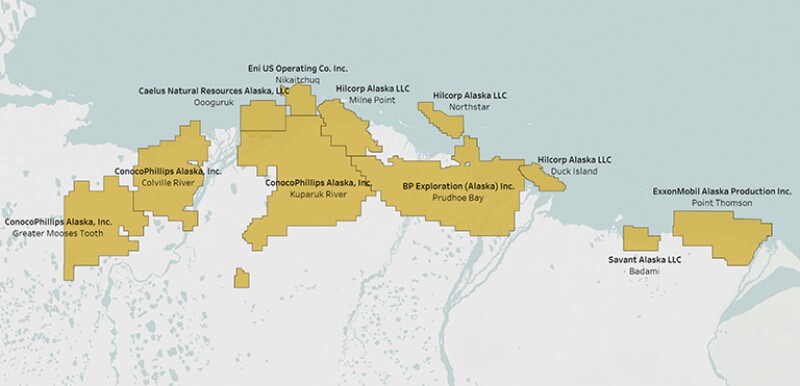

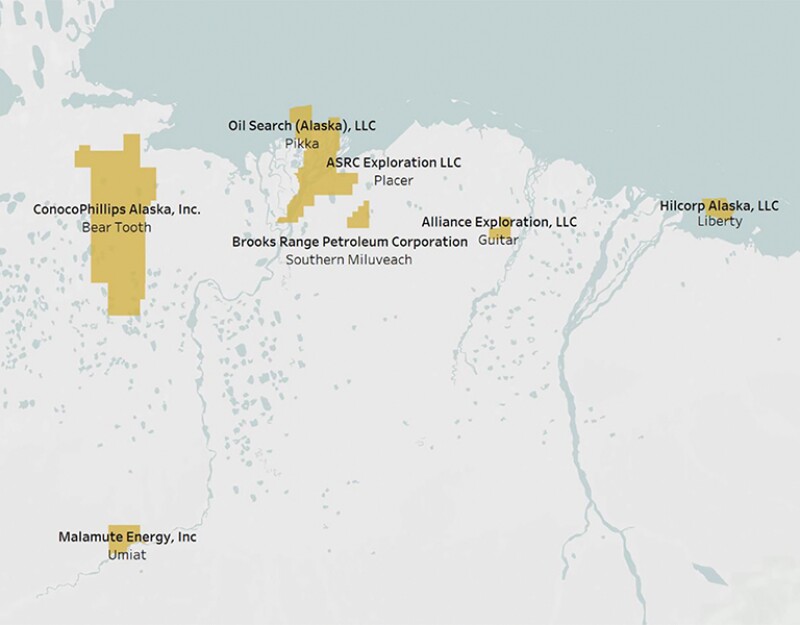

The list of Alaska-focused companies contained in the report suggests that interest remains strong in the US Arctic among majors and independents alike, though that interest might change directions when politics affect the economics of projects.

Nonetheless, between ConocoPhillips’ Willow project, recent discoveries by Australia’s 88 Energy, Shell’s renewed interest in returning for another bite at the exploration apple, and Hilcorp Energy Corp.’s acquisition of BP’s Alaskan assets—the North Slope may be in for a renaissance.

BP, which started drilling at Prudhoe Bay in 1968 and helped build the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), sold its upstream and midstream Alaska business to Hilcorp Energy Corp. in a $5.6-billion deal announced in 2019 in a spinoff that was more about raising cash to pay off liabilities related to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill than it was about the Arctic.

The sale made Hilcorp one of the largest privately held E&P companies in the US, the second-biggest producer in Alaska after ConocoPhillips, and the state’s largest supplier of natural gas, according to Hilcorp’s website.

Hilcorp debuted on the North Slope only in 2012, but as a result of the BP acquisition it now controls infrastructure in Prudhoe Bay, which is vital to bringing new production on stream. The EIA says Prudhoe Bay is North America’s largest oil field.

Another, even more recent newcomer is Australian independent 88 Energy which confirmed its discovery of an estimated 652 million bbl in recoverable reserves based on results of its Merlin-1 appraisal well, drilled in Q1 2021 in the southeastern regions of the National Petroleum Reserve.

In an investor presentation in August, 88 Energy reported that it drilled the Merlin-1 well to a depth of 5,267 ft, intersecting several oil-bearing sequences of Nanushuk sands. The Alaska Journal of Commerce reported that the formation was first identified by the Repsol-Armstrong Energy partnership in 2014 in the Pikka project that another independent, Oil Search, is currently developing.

88 Energy told investors it will drill a second appraisal well, Merlin-2, in Q1 2022.

Then there is Shell which began producing in Alaska’s Cook Inlet in the 1960s and seemed to be souring on Alaska when it stopped exploring in the Chukchi Sea in 2015. In the autumn of 2020 however, Shell’s offshore unit applied to form the West Harrison Bay Unit offshore from the state’s National Petroleum Reserve with plans to reboot its North Slope drilling and exploration activities in 2023 and 2024.

Also notable on the AOGA list are Chevron, Eni, ExxonMobil, and Marathon, which don’t seem to be leaving the scene anytime soon and most of which have exploration programs in the works for early in this decade.

For Further Reading

The Role of the Oil & Gas Industry in Alaska’s Economy (2020), Alaska Oil and Gas Association.