As unconventional reservoirs mature, operators are increasingly looking for innovative methods to enhance production from existing wells. Traditional stimulation techniques, such as acid treatments, have been borrowed from conventional reservoirs, but their effectiveness in tight shale formations is often limited.

An alternative approach gaining traction is chemical restimulation, which aims to improve well productivity by addressing near-wellbore damage, restoring fracture conductivity, and optimizing fluid flow through targeted chemical treatments. Unlike acid jobs, which primarily rely on wellbore scale dissolution, chemical restimulation can be tailored to the specific conditions of a reservoir, making it a more versatile and scalable solution.

By utilizing low dose rates of chemistry, larger volumes can economically be injected allowing for contact of the fractures and facture-matrix interface. This article explores the advantages of chemical restimulation over acid treatments, highlighting how it can improve production economics and extend the productive life of unconventional wells.

Chemical Restimulation vs. Acid Jobs

As operators manage their well inventory development more carefully, the industry seeks innovative methods to increase production from existing wells. This has led some well operators to borrow methods from conventional reservoirs and attempt to use acid treatments to stimulate production on existing wells.

Acid, particularly hydrochloric acid (HCl), has an extensive history of being used for stimulation of conventional carbonate reservoirs and to dissolve acid-soluble scales in the wellbore. Translating the use of acid to stimulate horizontal, multistage fractured wells in tight formations presents numerous challenges.

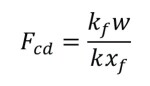

One way to measure the productivity of an unconventional well is dimensionless conductivity, as shown in this equation:

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . (Eq. 1)

Where:

kf = fracture permeability

w = fracture width

k = matrix permeability

xf = fracture half-length

The primary mechanism for acid to increase fracture conductivity is to enhance matrix permeability through the dissolution of carbonate minerals. Therefore, understanding the reservoir mineralogy is critical. For example, the Eagle Ford formation located in south Texas is calcite- and clay-rich, quartz-poor with carbonate content upwards of 70% by volume (SPE 165689).

This is contrasted with the Wolfcamp A formation located in the Permian Basin which is an organic-rich siliceous shale where over 60% of the rock is quartz and feldspar with the balance composed of clays and carbonate minerals (URTeC 2901968).

The probability that an acid-stimulation treatment will contact facies with high carbonate content will vary by reservoir and, more importantly, the acid volume that would be required to contact the matrix is significant.

One method to frame the required volume is by using the fracture pore volume (FPV) which utilizes the proppant used during the completion to estimate volume within the propped fractures (URTeC 3867194). Assuming a modern completion has a perforated interval of 10,000 ft and a proppant intensity of 2,000 lbm/ft, the FPV is 11,500 bbl.

Acid-treatment volumes typically cannot economically exceed 1,000 bbl, presenting the challenge of meaningfully contacting any matrix rock. With limited ability to improve matrix permeability, the dominant mechanism of using acid in unconventional wells is dissolution of scales.

Scale deposition is a real challenge, but its prevalence will vary not only across different formations but even within the same reservoir.

Scale deposition is typically contained to the wellbore, and in a 10,000-ft lateral, the wellbore volume is approximately 200 bbl. Therefore, at most, 200 bbl of acid would be required for scale dissolution, and it is likely that less is needed as it is improbable the entire wellbore is full of scale.

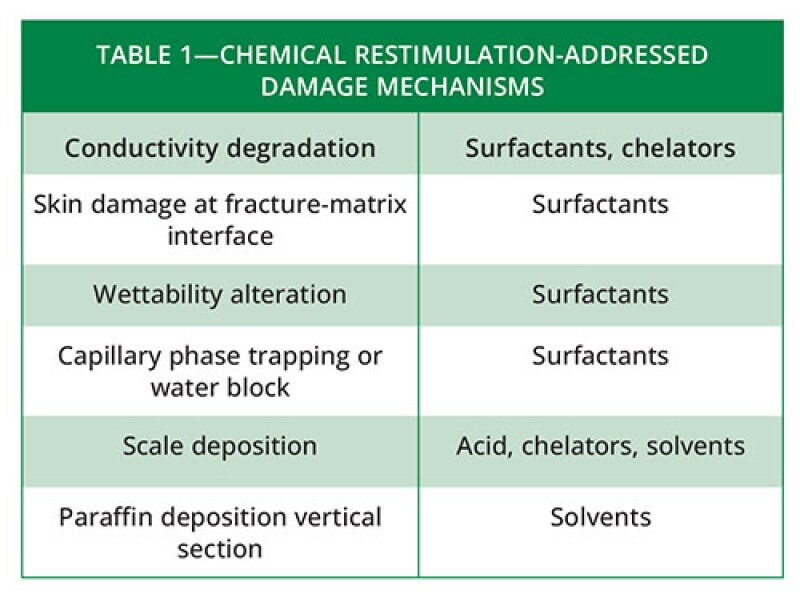

Unlike acid treatments that primarily dissolve acid-soluble scales, chemical restimulation treatments address multiple production-hindering factors such as fracture conductivity degradation, wettability alteration, capillary phase trapping, and scale deposition (Table 1). By leveraging surfactants, acids, chelators, and/or solvents, chemical treatments improve fracture conductivity, enhance fluid flow, and clean the wellbore more effectively.

Chemical restimulation treatments utilize chemistry at low dose rates and relatively low acid volumes allowing for the economic injection of significantly larger volumes than acid jobs. Chemical restimulation treatment volumes will vary with proppant intensity, but a typical volume will be between 5,000 to 15,000 bbl allowing for penetration into the propped fracture network and limited penetration into the matrix.

A critical aspect of these treatments is the use of chemical diverter to improve fluid distribution along the lateral. This allows for no mechanical intervention and injection from surface, significantly reducing the cost of these treatments.

Acid Treatment vs. Chemical Restimulation in the Eagle Ford

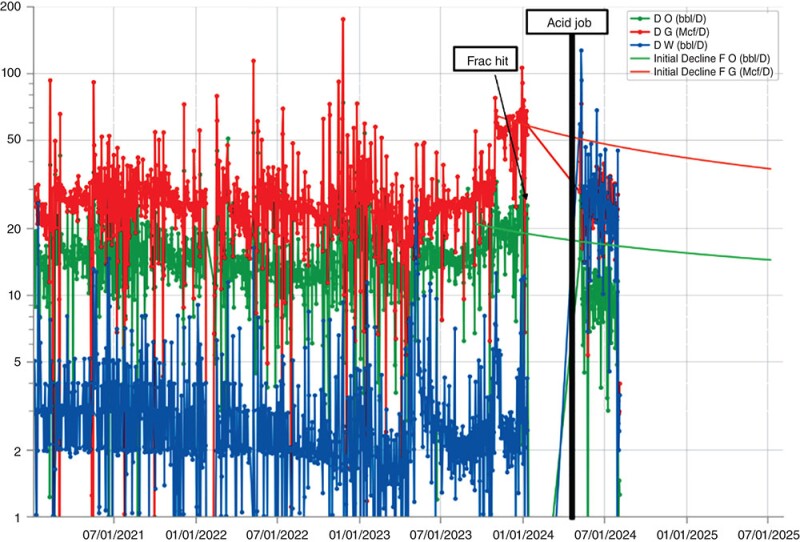

An Eagle Ford well located in south Texas, completed in 2013, was subjected to an acid treatment in 2024 after experiencing a fracture-driven interaction (FDI). The original completion featured a 3,532-ft perforated interval with 12 fracture stages and 2.4 million lbm of proppant. The calculated fracture pore volume was 687 bbl, and the wellbore volume was 344 bbl.

The treatment plan included 800 bbl of 15% HCl and 800 bbl of water with additives such as a corrosion inhibitor, iron control agent, and nonemulsifier. Due to cost constraints, the acid volume was relatively small compared to the FPV, even in an older completion with low proppant intensity. To enhance coverage, chemical diversion technology was employed.

The treatment was executed in April 2024, and we observed limited surface pressure response during injection. The well returned to production in May 2024.

The pre-FDI oil-production rate was approximately 20 B/D of oil and has now leveled out at 10 B/D while also observing a drop in gas from 60 to 30 MMscf/D (Fig. 1).

Overall, the acid treatment appeared to have limited impact on the damage caused by the FDI, with production still being adversely affected by it.

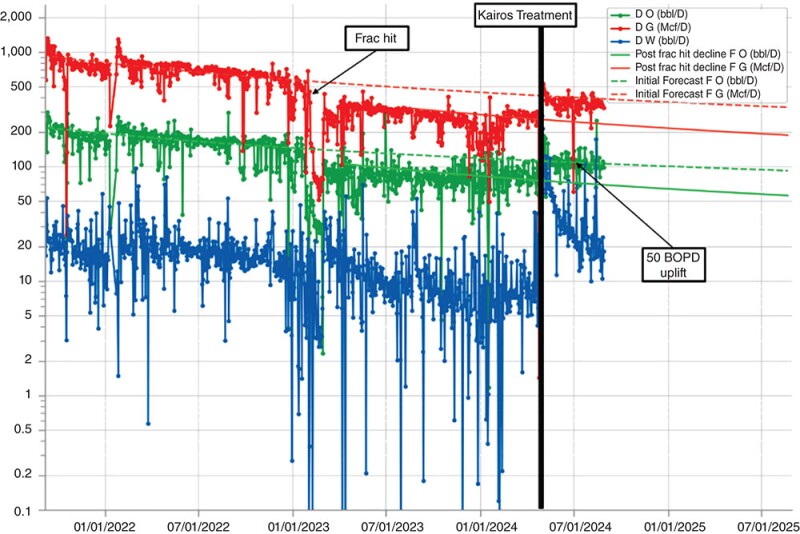

Kairos performed a chemical restimulation treatment on a three-well pad in the Eagle Ford (Fig. 2), where all wells had experienced FDI hits. The wells, completed in 2017, collectively lost about 50 B/D due to FDI-driven interactions.

The treatment designs focused on expanding the effective treatment volume beyond the wellbore and into the propped fractures and fracture-matrix interface. The approach combined a surfactant, acid-solvent blend, and diversion technology to address damage mechanisms such as wettability alteration, capillary phase trapping, and scale deposition.

Key design parameters included:

- Average proppant per well: 6.1 million lbm

- Estimated FPV: 3,500 bbl per well

- Treatment volume: 7,600 bbl per well, a 2x FPV multiplier for enhanced penetration

Lab testing determined that 1 gpt of surfactant provided optimal performance. It reduced oil/water interfacial tension by two orders of magnitude, lowered surface tension by 50%, and decreased the oil-contact angle by 40%. Additionally, 5,000 gal of acid-solvent chemistry were used—using only 15% of the volume in the acid-only treatment—to target scale and paraffin deposits.

Diversion played a crucial role in distributing treatment fluids across the lateral. Pressure-response analysis indicated successful stage-by-stage diversion, ensuring even chemical placement.

Following the treatments, the three wells’ oil production increased by approximately 50 B/D, returning to pre-FDI trends. The decline rate stabilized, resulting in sustained incremental production. With a net oil price of $65/bbl and gas at $2.05/MMscf of gas, the three-well treatment program paid back in 70 days.

Powder River Basin Fracture-Conductivity Improvement

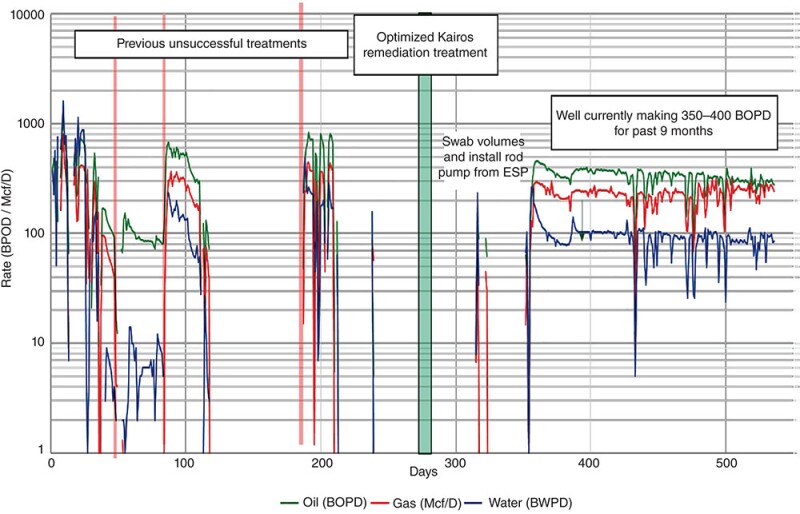

A new well located in the Powder River Basin in Wyoming came online at 700 B/D. However, production quickly declined, and a “gummy bear”-like material was collected from the separator.

Lab analysis of the solid showed it was primarily composed of iron and the polyacrylamide friction reducer. This is prevalent in iron-rich formations where high molecular weight polyacrylamide friction reducers are used (Rassenfoss, JPT).

Historically, citric acid in concentrations of 5 to 15% were used to remediate this type of damage. Citric acid is expensive, limiting the volume that can be economically injected. Since the friction reducer moves with the proppant into the fractures, the formation of this material extends beyond the wellbore.

The operator conducted three separate 10% citric acid jobs with volumes ranging from 200 to 500 bbl. In each case, the production post-treatment was briefly restored and then fell off, followed by additional gummy bear production.

A lab dissolution study was initiated to study the dissolution of the material using various chelator-based chemistries.

A chemistry blend of chelators and scale inhibitors demonstrated comparable performance in dissolving the sample to 10% citric acid, but at a dose rate of 5,000 ppm.

This represents a two-order-of-magnitude reduction in the chemistry dose rate compared to 10% citric acid, enabling the economic injection of significantly higher volumes.

The FPV of the well was 2,200 bbl, and a treatment volume of 2,700 bbl, comprising chelator and surfactant with a diverter, was designed to distribute fluid throughout the fracture network.

Post-treatment, the well returned to a production rate of approximately 400 B/D and sustained that production for more than 9 months with no gummy production (Fig. 3).

This case study demonstrates that using optimized chemistry in an engineered chemical restimulation treatment can enhance the economics of unconventional production.

Conclusions

While acid treatments have proven effective in conventional carbonate formations, their application in unconventional reservoirs is inherently limited.

The significant volumes of acid required to contact the matrix rock means the primary role of acid in these wells is limited to wellbore scale removal rather than meaningful reservoir stimulation.

Given these challenges, alternative chemical restimulation techniques offer a more viable solution for enhancing production in unconventional reservoirs. By leveraging advanced chemical formulations tailored to the specific properties of the reservoir, operators can achieve more effective, scalable, and economically viable production enhancement strategies.

As the industry continues to seek optimized approaches for maturing assets, chemical restimulation stands out as a promising alternative to traditional acid treatments.

For Further Reading

SPE 165689 Effect of Low-Concentration Hydrochloric Acid on the Mineralogical, Mechanical, and Physical Properties of Shale Rocks by S. Morsey, C.J. Hetherington, and J.J. Sheng, Texas Tech University.

URTeC 2901968 Interpretation of High-Resolution XRF Data From the Bone Spring and Upper Wolfcamp, Delaware Basin, USA by B. Driskill, and J.Pickering, Shell Exploration and Production Co.; and H. Rowe, Premier Oilfield Laboratories.

URTeC 3867194 Multibasin Case Study: Remediating Damage From Fracture-Driven Interactions Utilizing a Rigless Chemical Process by M. Lantz, R. Nelms, and D. Garza, Kairos Energy Services; and J. Trivedi, University of Alberta.

Solving the Gummy Bears Mystery May Unlock Greater Shale Production by S. Rassenfoss, JPT.

Michael Lantz is the cofounder and president of Kairos Energy Services. He has over 15 years of experience in the oil and gas industry with a focus on innovating new methods to improve reservoir recovery. He holds a BS in chemical engineering from the Colorado School of Mines and an MSc in global energy management from the University of Colorado.

Cooper Mazon is the director of engineering at Kairos Energy Services, bringing over a decade of experience in completions, production optimization, and enhanced oil recovery. Before joining Kairos, he held leadership roles at Rolls-Royce Power Systems and Nalco Champion, where he managed technical sales and spearheaded unconventional reservoir solutions across the US. His expertise spans well completions, chemical applications, and project execution. Mazon began his career as a completion tools engineer at Halliburton. He holds a BSc in mechanical engineering from the University of St. Thomas.